Allies and Enemies: How the World Depends on Bacteria (10 page)

Read Allies and Enemies: How the World Depends on Bacteria Online

Authors: Anne Maczulak

Tags: #Science, #Reference, #Non-Fiction

With this history as a backdrop, Yersin and Kitasato hardly stood a

chance of reaching an agreement on who had discovered the plague

pathogen. Kitasato would unsuccessfully argue for the rest of his career that his discovery was the same as Yersin’s, but Yersin received the accolades. He named the microbe

Pasteurella pestis in honor of his boss. (Microbiologists still treasure the compliment of having a lethal pathogen named after them. The species would be renamed Yersinia pestis

in 1944.) Historians have had trouble finding evidence in Kitasato’s notes to confirm his discovery of the plague bacterium. A new generation of microbiologists would try to smooth the prickles by conceding that Kitasato had probably seen the same bacteria in his

microscope that Yersin had spotted.

Pasteur and Koch never resolved their differences and Pasteur

remained a French patriot to the end. In 1895, the Berlin Academy of

Sciences extended a peace offering to Pasteur by inviting him to accept the medal of the Prussian Order of Extreme Merit. The

Frenchman refused any invitation to Germany as long as it still held

Alsace and Lorraine.

Unheralded heroes of bacteriology

The names Pasteur, Lister, and Fleming represent significant

advances in bacteriology but, as in today’s technical fields, the rise to prominence results as much from personality as it owes to scientific merit. Generations of scientists since van Leeuwenhoek’s day pursued the secrets of bacteria with the same devotion as more famous

chapter 2 · bacteria in history

51

microbiologists. Many of their stories have been all but lost due to oversight, misunderstanding of their discoveries, and sometimes

jealousy.

Robert Hooke

In the 17th century, Robert Hooke corresponded with Antoni van Leeuwenhoek on the assembly of lenses for viewing the natural world

on a microscopic scale. Both men developed similar instruments, but

van Leeuwenhoek would become known as the Father of Microbiology while Robert Hooke’s name has faded into near obscurity. A brilliant biologist and engineer, Hooke also mastered physics, the arts, architecture, geology, and paleontology over his long career.

As a youngster, a case of smallpox had disfigured Hooke, but he

compensated with a gregarious nature. By the time Hooke graduated

from Oxford, scientists in England sensed a luminary had arrived to

raise public opinion of their profession. In 1662, the Royal Society of London elected Hooke at age 27 as Curator of Experiments, a role

suited to his intellect and penchant for innovation. As Curator, Hooke

performed an impressive array of demonstrations in biology, chemistry, and physics for the Royal Society but had an increasingly hard

time staying focused on details from month to month. He often bolted to new projects before finishing the last, leaving other Society members to the drudgery of completing his studies.

Hooke tinkered with van Leeuwenhoek’s microscope design and

began a detailed study of the world he found under its lens. Hooke

drew sketches of insects, feathers, plants, and leaves as well as snowflakes and mineral crystals and published them in

Micrographia

in 1665. (The book’s full title is

Micrographia: Or Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses with Observations and Inquiries Thereupon .) In it he coined the term “cell” to describe similar but separate units that composed a thin slice of cork. Overlooked at the time, this remark laid the foundation for all of biology: the cell is the simplest basic unit of every living thing on Earth, and without cells life does not exist.

The breadth of Hooke’s accomplishments in architecture and

engineering are no less impressive, yet Royal Society records contain

52

allies and enemies

little mention of the man or his work. In 1672, mathematician Isaac

Newton out of Cambridge joined the Royal Society. Hooke had

already begun developing equations to describe the gravitational forces of Earth’s elliptical orbit around the Sun when Newton arrived

at the Society with expertise in this same subject. The frail, intro-verted Newton developed a rapport with the outgoing Hooke as they pondered the mathematics of planetary movement. Their alliance permanently dissolved when in 1672 Hooke publically criticized a presentation to the Society by Newton on the properties of light and

color. The animosity grew over the next decade. Hooke accused Newton of claiming credit for theories Hooke felt he had already developed. When in 1687, Newton published a thesis on planetary orbits with no mention of Hooke, the rift seemed irreparable.

Hooke’s personality disintegrated in later years for reasons

unknown. Isaac Newton would be one on a long list of people to whom Hooke directed his animosity. Newton took the Curator position shortly after Hooke’s death in 1703 and almost at once struck Hooke’s name from Society documents. Hooke’s portrait disappeared

under suspicious circumstances as well as many of his laboratory notes. Some historians believe those missing notes contain evidence

that Hooke invented the compound microscope rather than van

Leeuwenhoek, and questions persist on whether Hooke had developed the theory of gravity before Newton. Hooke would sadly

become known as much for his rivalry with Isaac Newton as for his

contributions to science.

John Snow

Epidemiology owes its beginning to a London doctor’s dogged

attempt to stem one of several cholera outbreaks that had tormented

London in the 1800s. Physician John Snow wrote in his journal in September 1854, “The most terrible outbreak of cholera which ever

occurred in this kingdom is probably that which took place in Broad

Street, Golden Square, and the adjoining streets, a few weeks ago.”

Snow’s nonplussed colleagues knew of his tedious house-by-house

chapter 2 · bacteria in history

53

assessment of family health and daily habits near the outbreak’s center in Soho. The details he collected from the interviews seemed to

have nothing to do, however, with the debilitating diarrhea that claimed many of the afflicted.

Snow persevered and sifted through his stacks of notes. He found

that 73 of the outbreak’s 83 deaths occurred within two blocks of a

pump (see Figure 2.4) that dispensed water free to the public. The

incidence of diarrhea related to the frequency in which families used

the pump. By simply removing the pump’s handle to make it unusable, Snow stopped the 1854 Soho cholera outbreak. He would

become known as the Father of Epidemiology. Today’s epidemiology

follows the same path used by Snow. Epidemiologists track the loca—

tions where disease incidence are highest and search for commonalities among the sick. They gather other clues, such as an increased reporting by doctors and hospitals of common symptoms. Epidemiologists have even identified the presence of a waterborne outbreak by the uptick in sales of toilet paper in a community.

Snow conducted his study without any idea of the pathogen coming from the pump. His contemporaries had not connected water

with many of the diseases of the day. Thirty years after the Soho outbreak, German microbiologist Robert Koch identified

C. vibrio

as the cause of the waterborne disease.

George Soper

In 1883 Irish immigrant Mary Mallon arrived in New York City and

found work cooking for well-to-do families. In the summer of 1906,

Mary escaped the city heat and took a job at the rented cottage of banker Charles Warren in Oyster Bay, Long Island. Soon afterward

Warren’s family and staff suffered headaches, lethargy, loose bowels,

and debilitating fever. The family doctor recognized the symptoms of

typhoid fever but doubted an inner-city disease would afflict subur—

bia’s wealthy.

54

allies and enemies

Figure 2.4 The Broad Street pump. London has preserved the Broad Street pump as a historic site where John Snow stopped a deadly cholera outbreak.

Prior to Snow’s accomplishment, most doctors did not believe water carried disease. (Courtesy of Peter Vinten-Johansen, et al.,

Cholera, Chloroform, and the Science of Medicine: A Life of John Snow , 2003, 289; and http://johnsnow.

matrix.msu.edu/images/online_companion/chapter_images/fig11-2.jpg)

By summer’s end the Warrens had recuperated and returned to

the city. The house’s owner, George Thompson, heard of the outbreak

and made a brilliant assumption: He suspected that a dangerous germ

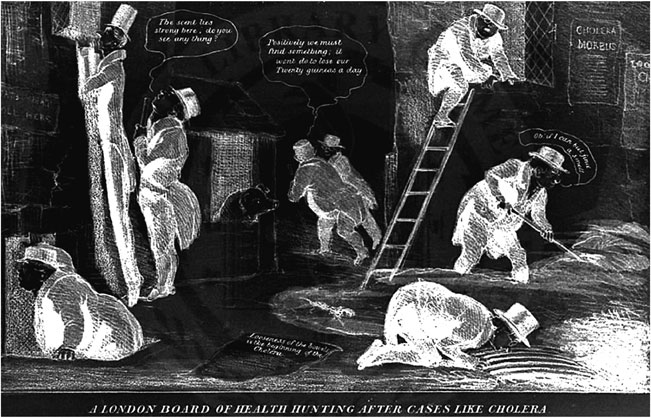

had entered his home. The Thompsons called on a public health officer, the fastidious, systematic, and humorless George Soper. Soper went straight to hands and knees at the Thompsons’ in search of dirt, an undertaking depicted in the satirical cartoon in Figure 2.5. He sat

for hours perusing household records and the comings and goings of

staff and visitors. Soper scoured details that few epidemiologists had

in the past. In a meal log, Soper noticed the Warrens’ fondness for ice

chapter 2 · bacteria in history

55

cream and sliced fresh fruit, excellent carriers of germs. He also noticed Mary’s name in the records at the time the Warrens got sick.

Soper hurried back to New York and unearthed health records showing that in seven of the eight families for whom Mary cooked, typhoid

fever broke out; 28 cases in all and three deaths.

The scent lies

strong here;

Positively we must

do you see

find something;

anything?

it won't do to lose

our Twenty guineas

a day.

Oh, if I ca

find

n

a s b

m u

e

t

ll.

Figure 2.5 Health inspectors react to newspaper headline, “Looseness of the Bowels is Beginning of Cholera.” (Courtesy of Wellcome Library, London; The John Snow Archive and Research Companion, Center for the Humane Arts, Letters, and Social Sciences online at Michigan State University)

Soper tracked down Mary the next year working in a Park Avenue

apartment. With little formality he accused her of spreading death and

disease and ordered her to surrender a fecal, urine, and blood sample

on the spot. Husky and with a lightning temper, the cook hustled Soper out the door and into the street. Undaunted, he showed the city’s Health Department his evidence and demanded action against the cook. Authorities felt Park Avenue was as unlikely a place for typhoid fever as Long Island, but Soper’s meticulous notes swayed them. Police wrestled Mary out of the apartment and took her to Willard Parker Hospital, the main center for treating contagious diseases. There, doctors found unusually high concentrations of Salmonella typhi in her stool and the legend of “Typhoid Mary” was born.

56

allies and enemies