Allies and Enemies: How the World Depends on Bacteria (8 page)

Read Allies and Enemies: How the World Depends on Bacteria Online

Authors: Anne Maczulak

Tags: #Science, #Reference, #Non-Fiction

needless fatalities from infections of battlefield injuries. Before the magic bullet arrived, herbs served as the main way to fight infectious disease, with mixed results.

Evidence of TB predates written historical records.

Mycobacterium bovis

may have entered the human population between 8000

and 4000 BCE with the domestication of cattle. Samples from the spinal column of Egyptian mummies from 3700 BCE have shown

signs of damage from the disease, but no one has determined if the

infection had come from

M. bovis

or the cause of modern TB, M. tuberculosis. The distinction is small because these two species share more than 99.5 percent of their genes.

In 400 BCE Hippocrates identified the most widespread disease

in Greece as phthisis and in so doing described classic signs of consumption or TB. In

Aphorisms

, he warned, “In persons affected with phthisis, if the sputa which they cough up have a heavy smell when poured upon coals, and if the hairs of the head fall off, the case will prove fatal.” The infected transmit the TB pathogen when they

40

allies and enemies

cough, sneeze, or merely breathe, and dense population centers have

always acted as breeding grounds. Today TB infects one-third of the

world’s population, and humans, not cattle, serve as the reservoir.

Bubonic plague, syphilis, and anthrax began appearing with regularity about 2000 BCE. Historians have debated the message

intended by historian Ipuwer, who sometime between 1640 and 1550

BCE wrote of the Egyptian plagues. In referring to the Fifth Egyptian Plague he wrote, “All animals, their hearts weep. Cattle moan.”

This passage seems to describe anthrax, a disease as deadly in animals

as in humans.

Mobile societies enabled infectious diseases to reach wider distribution. Infectious agents traveled with Egyptian and Phoenician

traders crisscrossing the Mediterranean between 2800 and 300 BCE.

Both cultures sent ships into the Red Sea and to Persia, but the Phoenicians also sailed north along Europe’s coast. If local residents

managed to evade syphilis-infected sailors, they might have contracted

disease from some of the tradable goods infested with parasites and

pathogens. Anthrax endospores, for instance, hid in hides, pelts, and

wool that held bits of soil. As each ship docked, rodents undoubtedly

clambered down gangways and brought bubonic plague to shore.

Anthrax became a disease of laborers. Anyone who worked their

hands into the soil had a much greater chance of inhaling

B. anthracis endospores or infecting a cut. Shearers, tanners, and butchers also had higher incidences of the disease than the rest of society. Since livestock also picked up the microbe from the ground, anthrax caused occasional epidemics in agriculture. The Black Bane of the 1600s killed nearly 100,000 cattle in Europe. People do not transmit anthrax to each other; infection comes mainly by inhaling endospores from the environment. When B. anthracis germinates in the lungs, mortality rates reach 75 percent of infected individuals. Today, the United States has less than one case of anthrax a year. Slightly higher rates occur in the developing world.

Syphilis-causing Treponema might also have entered the human

population from animals, perhaps in tropical Africa. Bacteria similar

to the one causing human syphilis—the Great Pox—were isolated in

1962 from a baboon in Guinea, but few other clues about the origin

of syphilis exist. Ancient explorers brought syphilis throughout the

chapter 2 · bacteria in history

41

Mediterranean and Europe. Its migration mirrored the spread of the

major bubonic plagues that followed trade routes west from Asia to

Europe, and later followed the slave trade from Africa to the western

hemisphere. Syphilis additionally accompanied each of history’s

armed invasions.

Disease historians diagnose syphilis in skeletons by looking for the presence of caries sicca (bone destruction) of the skull, which gives the bone a moth-eaten appearance plus characteristic thicken—ing of the long bones. Corkscrew-shaped T. palladium wriggles into the testicles where it reproduces and then infects a sexual partner by similarly burrowing into the skin. The bacteria then enter the lymph

system and bloodstream. As syphilis progresses, the skin, aorta, bones, and central nervous system are affected, but the disease’s early-stage signs are so nebulous that misdiagnosis persisted for centuries. Physicians could not distinguish syphilis from leprosy until Europe’s first major syphilis outbreak from 1493 to 1495 in Naples, which remains one of history’s worst syphilis epidemics. The siege of

Naples has also been implicated as the origin of syphilis in the New

World, a debate that continues to this day.

In 1493, France’s Charles VIII claimed Naples as his by

birthright and sent his army to wrest it from Spain. During the clash,

syphilis spread from Naples to the rest of Europe. The timing of the

siege and Christopher Columbus’s voyages from Spain have convinced some historians that Columbus’s men brought syphilis to the

Americas. Columbus left the port of Palos, Spain, with three ships and 150 men in August, 1492, and returned in March, 1493, leaving dozens of his crew on the island of Hispaniola. The next two excur—sions from Cadiz to Hispaniola totaled 30 ships and at least 2,000 men

with return crossings in 1494 and 1495. After each voyage, most of

Columbus’s men wanted no more part of the open ocean and earned

money by joining ranks with the Neapolitan troops to fight the French. When Naples finally rebuffed the invasion in 1496, Charles’s troops returned home and syphilis went with them.

Writings by European physicians from 1497 to 1500 indicate that

they had never before seen the disease that had first victimized Naples. The French called syphilis “the disease of Naples,” but the Italians felt equally sure of the source. In 1500, Spanish physician

42

allies and enemies

Gaspar Torella wrote, “On this account it was christened the morbus Gallicus by the Italians, who thought it was a disease peculiar to the French nation.” The argument would never be resolved and the finger pointing probably continued for years.

Did Christopher Columbus’s ships bring syphilis to the Americas

as many historians believe? Martín Alonso Pinzón captained the Pinta in Columbus’s first voyage. A bitter rival of Columbus throughout their sailing careers, Pinzón died of syphilis in 1493 soon after returning home to Spain. Although symptoms begin earlier, the fatal stages of the disease can arise 10 to 20 years after infection, which suggests that Pinzón may have contracted syphilis well before 1492. Before sailing with Columbus, Pinzón had voyaged along the African coast and to the Azores, widening the possibilities of where he caught syphilis. Although speculation on whether Columbus brought vene—real disease to the Americas persists, the establishment of settlers’

colonies would have increased the chance for disease transmission. If

not Columbus, then certainly others who followed brought with them

contagious diseases.

The plague

Justinian I, 6th-century ruler of the Byzantine Empire, devoted himself to spreading Byzantine architecture from his throne in Constantinople, along the Mediterranean rim, up the Nile, and deep into Europe. To prepare for his fleet’s voyages, Justinian ordered continuous stocking of the massive granaries on the city’s outskirts. The grain sustained the ships, but also fed an exploding rat population.

By 540 CE Justinian had succeeded in expanding Constantinople’s influence. But at each new port, residents fell nauseous and developed chills, fever, and headache, some within only two days of a ship’s arrival. Their abdomen would swell with pain and bloody diarrhea followed. Their lymph nodes (or buboes) clogged with necrotic tissue and by six days of the first discomfort, many had died, the skin covered with dark purple lesions. The same occurred in Constantinople where deaths grew to 10,000 daily. Many who felt the first symptoms of illness panicked and fled to the countryside. Within days the fatalities rose in those rural places, too.

chapter 2 · bacteria in history

43

Justinian blinded himself to the misery and more than one assas—

sination attempt. He drained the coffers to expedite his dream and

perhaps also to entice new sailors from a dwindling labor pool. The

Plague of Justinian would kill 60 percent of the empire or 100 million

people by the time it had run its course in 590 CE. Justinian himself

avoided the plague and died of natural causes at age 38.

Did a mitigating factor suddenly appear to cause the first bubonic

plague in recorded history to arise? Rodents then as now carry the intestinal bacterium Y. pestis that can contaminate the animal’s fur or skin. Fleas ingest Y. pestis each time they bite and so engorge themselves that their digestive tract fills with bacteria. The insect must regurgitate some bacteria just to stay alive. When a flea upchucks on an uninfected rodent, it transmits Y. pestis and creates an ever-expanding reservoir of disease. Poor sanitation leading to large rat populations in metropolises like Constantinople increased the proba—bility of receiving flea bites. Justinian gave the epidemic a boost by

building granaries that all but guaranteed a massive rat colony to serve as the disease’s reservoir.

Following Justinian’s rule, bubonic plagues mysteriously disappeared for the next 700 years. As the last remnants of Roman influence faded, disease control also declined, and many contradictions took root. People believed that retaining wastes and even an animal carcass in the home repelled evil and thus disease, yet many also assumed that bad odors brought illness—a cadaver in the living room surely smells. Even with the building of the first centralized hospitals at the dawn of the Middle Ages, medicine remained the domain of healers who used leeches for extracting the body’s pains. Faulty birthing methods caused a high incidence of mental illness that further threatened good personal hygiene.

Beginning in the 14th century, four plague epidemics would decimate Europe, none more brutal than the Black Death, named for the

black-purplish lesions formed by hemorrhaged vessels under the skin.

Between 1346 and 1352 the Black Death killed more than 25 million

people in Europe or about 30 percent of the total population. Combined with the loss of life as the plague followed trade routes from Asia in the 13th century and to northern Africa and the Crimea before reaching Europe, the global Black Death killed a total of 200 million.

44

allies and enemies

As in Justinian’s day, survivors could not bury the dead fast enough.

Survivors carried the corpses on long poles—“I wouldn’t touch that

with a 10-foot pole”—to mass graves outside the towns. The epidemic

slowed only when it reached the Alps where colder weather repelled

rats, and the pathogen had likely mutated to a less virulent form.

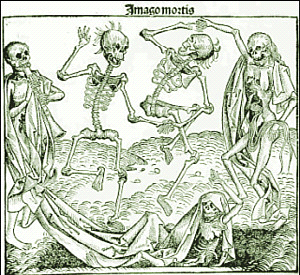

Figure 2.2 Dance of Death. Death became an everyday occurrence, by the hundreds in some towns, in the Middle Ages in Europe. Artists, writers, and composers depicted bleak futures where Death overwhelms the living.

An epidemic that destroys 100 million lives in less than a decade

and reduces Europe’s population by one-third, as the Black Death did, certainly impacts society in ways that are felt for generations.

Even art and music reflected the looming presence of Death, which

usually triumphed over mortals (see Figure 2.2). Some cities lost 75 percent of their children, and entire family trees had been reduced to one individual—the plague had created a parentless generation. Craftsmen, artists, farmers, and clergy disappeared. A plunge in economic vitality caused birth rates to drop.