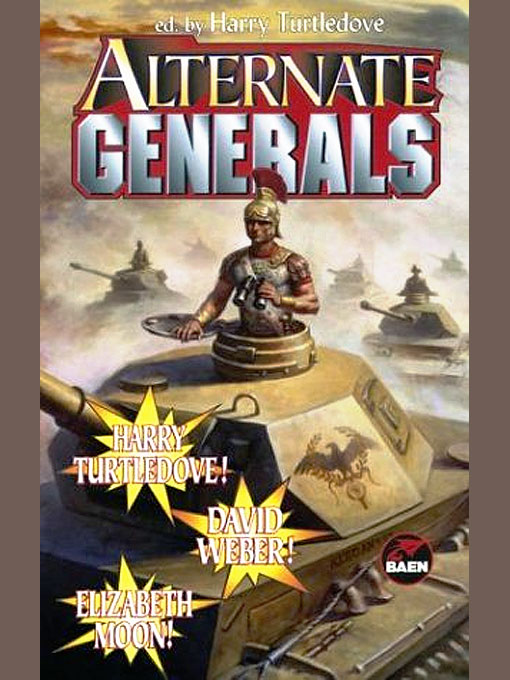

Alternate Generals

Read Alternate Generals Online

Authors: Harry Turtledove,Roland Green,Martin H. Greenberg

Tags: #Science Fiction

Alternate Generals

Alternate GeneralsHarry Turtledove,

Roland Green &

Martin Harry Greenberg

The Test of GoldCopyright © 1998 by Harry Turtledove, Roland Green & Martin Harry Greenberg. All stories copyright © 1998 by the individual authors.

ISBN: 0-671-87886-7

Cover art by Charles Keegan

First printing, August 1998

Distributed by Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Typeset by Windhaven Press, Auburn, NH

Printed in the United States of America

Lillian Stewart Carl

The old man lowered himself carefully onto the couch. Every day the pain in his belly grew worse. By winter he'd be at rest in the tomb of his ancestors beside the Appian Way. He'd had a long life, as soldier and merchant, and if Mars, Mercury, and Mithras called him, so be it. But there was something he had to finish first.

Through the opening of the atrium he could just see Caligula's old bridge between the Palatine and the Capitoline, a hard marble angle against the glare of the summer sky. A beam of sunlight touched the door of the room. The air was warm and still. Even so he felt cool, as though the rectangular porphyry panels and columns of his home exuded a chill.

Unless it was simply the memory of chill. He leaned closer to his table, spread out the scroll, and started to read what he'd already written.

Ave

. I was named C. Marcus Valerius after my father and tutored by the best Greek slaves. At the age of twenty, in the sixth year of the reign of Nero Augustus, I was made a military tribune and assigned to the staff of Catus Decianus, procurator of the province of Britannia. My mother and sisters wept to see me off to the very edge of the earth, but my father reminded me I was now beginning a brilliant career.

The road through Gaul was long. The farther north I went the colder the wind grew and the more sullen the rain. But the coarse humor of my little band of legionaries never faltered. One auxiliary from Iberia, called Ebro after his native river, jested even with me. At first I took offense. Then I realized that Ebro had many campaigns beneath his corselet, while I had none, and I learned to return gibe for gibe.

By the time we took ship across a rough gray sea and landed in Britannia I was wet through, unshaven, muddied from boot to helmet. And yet I could do no less than to press on, doing my duty, with that Roman honor which brought us not only an empire but the will to rule it.

In Londinium I presented myself to Catus Decianus. He had the small sleek head and obsidian eyes of a snake, and barely gave me time to bathe before he assigned me a task. "The king of one of the British tribes," he explained, "has lately died. He bequeathed half his property to the Emperor. As well he should, after all the trouble he caused us ten years ago. These barbarians are a stubborn lot. All we intended was to disarm them, and they had the gall to rebel."

I nodded as sagely as I could.

"The king's name was Prasutagus," Catus went on. "Of the Iceni, beyond Camulodunum. He has no male heir, so there's no question of the kingdom continuing. You're to make an accounting of the Emperor's property. I intend to deliver it to the governor when he returns from his campaign against the Druids."

Thanks to Ebro's stories I knew what he was talking about. "The Druids are the priestly class. They have great power, no Gaulish or British ruler will make a move without consulting with one."

If Catus was impressed with my knowledge, he showed no sign of it. "So it's in our best interests to stamp them out. Suetonius has them bottled up on some island in the northwest, and their women with them."

"I'd like to pay my respects to Gaius Suetonius Paulinus. And my father's. They campaigned together in Mauretania."

"Then you'd better get on with it, Tribune. Suetonius will be back before summer, his eagles draped with Druid gold. You don't want to still be mucking about in a barbarian village by then, do you?"

"No sir." I saluted. "Until I return, then, sir."

Catus was already unrolling a scroll, and dismissed me with a wave of his hand. I reminded myself I needed his good will to advance my career and set out on the next stage of my journey.

Londinium was little more than a cluster of merchant's wood and wattle houses around a bridge over the Tamesis, although I could tell from the new roads being driven outward in every direction that Suetonius intended the city to be a hub of commerce. The road north cut through marshland.

When I think of Britannia I think of water—the great river, the marshes, heavy clouds like sopping fleeces, unrelenting rain. There trees grow thick and forests thicker. But just as I decided Britannia was the soggy frontier of Hades itself, the rain ended and a warm wind rolled up the clouds. For the first time I saw the British spring, so many shades of green I couldn't count them and a sky of such rich blue as to put lapis lazuli to shame.

Camulodunum, an old tribal capital, had been made into a colonia for retired legionaries. This part of the country was pacified, and all the building work had gone into a vast temple to Roma and Claudius Augustus. Just completed, it stood square and proud—and, I had to admit, pretentious—among the mounds of the native huts. The natives themselves cleared away leftover stones, casting resentful glances toward the old soldiers who lounged on the steps.

Ebro spat onto the paving stones. He could say more with a glob of spit than most men with words. But, as befitted my dignity, I didn't ask whether he was reproving the native workers or our own veterans.

At last Venta Icenorum rose before us. Black birds swooped and croaked above huge circular earthworks. Human skulls grinned from recesses in the gateposts. The guards were tall blond men sporting fierce moustaches, hair swept back like horses' manes, and massive embossed shields. They greeted me civilly enough in their strange tongue, although there was a certain amount of sword and spear rattling as they conducted me through the town. By standing as straight as I could I made myself as tall as the shortest of them.

Women and children dropped their tasks and looked at me. Even the dark eyes of the cows and horses turned my way. My escort strolled along casually, but one sharp look from Ebro and my legionaries marched in good order.

The buildings were also circular, of wood pilings with conical thatched roofs. Inside the largest was a vast hall ringed with wooden pillars. A ray of sunlight struck through a vent hole in the roof. In the dimness beyond stood several more warriors. The king's guard, I assumed, now at loose ends.

But the warriors seemed more haughty than uncertain. Turning, they deferred to a figure who stepped through a curtained doorway. A woman. I waited a moment, but no one else appeared.

She was tall as the men, a full handsbreadth taller than me. She wore a dress and a cloak woven in squares of different colors. Holding the cloak was a gold brooch cunningly wrought in swirls of gold, decorated with enamel chips. About her neck lay a gold torc, strands of braided wire with animal-headed knobs resting against her white throat. Even her hair was gold, a startling golden red, braided and ornamented with beads. Her eyes were as blue as the British sky. They fixed on my face, looking me up and down in the same manner I'd inspect a horse, although I've never been quite so amused by an animal.

Everyone was looking at me. They expected me to deal with a woman. I made a show of removing my helmet and tucking it under my arm. "Ave. I am C. Marcus Valerius. I bring greetings from the Senate and the people of Roma."

"I am Boudica, queen of the Iceni. My husband was your ally."

Ally, not client, I noted. But I'd heard that these Britons were a proud people. "I'm tribune to Catus Decianus, procurator. I've come to make an accounting of your husband's legacy."

"I've never known a Roman," she said, "who'd let anything of value slip through his fingers."

I took her statement as a jest. Unless—well, no, her Latin was impeccable, she meant what she said.

She went on, in a low vibrant voice, "He left you half his property. The other half I hold in trust for my daughter, heir to the rule of the Iceni."

I glanced at the assembled warriors. But they couldn't understand what she was saying, no wonder they didn't seem unsettled by it.

"We'll hold a feast tonight, in your honor," concluded Boudica. "My men will show you and your men to your own house."

I realized I was standing there with my tongue stuck to the roof of my mouth. "Ah—thank you. We'd like a bath, after the long road. . . ."

She smiled so broadly crescent lines cleft her cheeks. "I'll have the servants bring you basins of water."

"Thank you," I said again, as though I were the client.

Boudica turned and went out through the curtain. Beyond it stood a brown-bearded man wearing a white robe and a collar of gold. Her head tilted toward his and she spoke. The curtain fell.

I made a neat about-face and strode back down the length of the building. My task here, I thought, wasn't going to be as simple as I'd first assumed. If Boudica's jewelry were any indication, the Iceni had more than a few trinkets worthy of Nero's coffers. And delivering such an accounting would certainly grease my path to advancement.

The old man put down the scroll. Someone was shouting in the street, and a wheeled vehicle rattled by, but the house itself was silent.

His belly hurt. He considered calling for his wife to rub his back, but no, she'd be in her garden, gathering the herbs for this afternoon's banquet. She'd prepare his porridge and soft meats with her own hands, as she usually did, but beneath her keen eye the cooks would make ready a sumptuous meal for a very special guest. Already a spicy odor hung in the air, but his appetite had deserted him long ago.

"Rufus!" the old man called in his reedy voice.

The servant materialized in the doorway.

"Let me know the moment my son arrives."

"Yes, master." The servant vanished again. A good man, Rufus. Marcus had left instructions in his will that he be freed. . . .

Not that the instructions in a will were always followed, were they? With a groan he picked up the scroll again.

Warriors and their women sat down together at the feast, ranged in a circle around a blazing fire in the center of the great hall. Servants passed meats, breads, herbs, and a Falernian wine as fine as any my father ever served at his table in Roma. I'd heard that the chief god of the Britons was Mercury, the patron of merchants. I began to see why.

Through the smoky gloom I caught again and again the gleam of gold, electrum, and gilded bronze. Everyone wore ornaments, brooches, necklaces—outside I'd seen even their splendid horses adorned with metalwork. Every ornament was designed in the living lines of plants, of horses' tails, of serpents. Our own utilitarian items seemed dull and flat.

Tonight Boudica's brooch held a cloak of green silk stitched with sinuous designs in gold thread. It rustled faintly as she motioned me to sit beside her and her daughters. They were lissome, red-headed girls of about fifteen and twelve, introduced as Brighid and Maeve. When I asked if Prasutagus had arranged marriages for them before his death the girls looked faintly shocked, but Boudica smiled.

She herself was perhaps five and thirty, past her youth but not beyond remarriage. I expected every tribal monarch across Britannia was vying for her hand. Even half the wealth of the Iceni would be a prize.

Every now and then one of the warriors hurled some boast at me, which Boudica translated, erring on the side of courtesy, I imagine. She made no move to reprove the mens' boisterousness. Her rule was probably only courtesy to their king's widow, I thought. She had no real power.

The white-robed man sat behind us. More than once I felt his eyes on the back of my neck, but every time I looked around his bearded face was bland. At last I asked Boudica who he was, thinking he was perhaps her brother and guardian.

"He is Lovernios," she replied. "My advisor."

The man himself nodded, with an amused smile identical to Boudica's. I'd never before found myself the butt of such a subtle joke. Was Lovernios a druid who'd escaped Suetonius's nets? Between my ignorance of the Iceni's customs and the delectable wine I was no doubt playing quite the fool. I made a note to pay closer attention.

The fire burned down and the faces of the Iceni grew red as Boudica's hair. But their taunts and the occasional gnawed bone were aimed more at each other than at my men, who sat to one side watching the scuffles as they'd watch a gladiatorial combat.

Boudica exchanged a look with Lovernios. He slipped out. Another man entered, raised an instrument like a lyre, and began to sing. "It's the story of a boar hunt," Boudica murmured, her breath piquant with wine and herbs. "He'll sing of bulls and horses and the deeds of our ancestors."

As a follower of Mithras, I understood the bull, and nodded.

The girls rose from their seats. "Good night, Tribune," said Brighid gravely, and little Maeve blushed and said, "Good night."