Amazing Tales for Making Men Out of Boys (23 page)

Read Amazing Tales for Making Men Out of Boys Online

Authors: Neil Oliver

On September 21, 1904, a doctor was summoned to examine the corpse of a Native American man who had died earlier that day on the Colville Reservation in Washington. It was the same month that saw Scott’s triumphant return to England.

He was 60 years old and had lived on the reservation since 1885, when the United States Government had seen fit to separate him from the younger members of his tribe. While the Indians were sent to a reservation set aside for their people, on land north of the Wallowa River beneath the Bitterroot Mountains, the old man was considered too dangerous to go with them. He might exert his baleful influence over the impressionable youngsters and turn them back to their old wild ways, and so, together with other senior members of the tribe, he was sent instead to Nespelem on the Colville Reservation. It was there that he lived out the remainder of his years, cut off from the blood and the land of his fathers.

The doctor made an examination of the old man’s body and was somehow able to record the cause of death as “a broken heart.”

In the language of his people—a language spoken then by only a handful of human beings left alive on the whole Earth—his name was Hin-ma-towya-lak-ket. To the white men who wrote about him later, he was Chief Joseph of the Nez Perces.

The destruction by Europeans of every civilization they encountered in the Americas—North and South—is an old and well-known story. Having crossed the Atlantic Ocean in the wake of Christopher Columbus, they were in no mood to put up with the sitting tenants they found occupying their New World. Relations

were briefly cordial in North America—in the early days when the incomers were still few in number and living space upon the vast new terrain was hardly an issue. But as the 19th century dawned and progressed, and with the immigrants numbering now in the millions, the people referred to today as Native Americans were systematically brushed off the page to make way for a new story.

This is what Europeans have always done, at home and abroad. The ancient history of Europe, as revealed by archeology, hints at innumerable occasions when one people has roughly displaced—or replaced—another.

Through centuries and millennia, waves of new peoples had arrived on British shores and muscled their way past existing populations on the way to creating new societies. The Picts gave way to Scots and to Vikings; Britons submitted to Romans, and then to Anglo-Saxons—who in turn fell before the Norman conquerors of 1066. But those vanished peoples survive only as names on a historian’s page, and some artifacts in the display cases of museums. In the case of the opening up of the Old West of North America, however, we have photographs of the men and women swept aside.

The stories of people like Lone Wolf, Cochise, Kicking Bird, Standing Bear and Sitting Bull would be heartbreaking enough even if only their names had survived. But seeing the unsmiling faces of those sentinels, who look right through the lens to accuse the world beyond, makes it that much harder to hear about their lives and deaths. This is bad luck for modern Americans. The land has been inherited from men and women who committed many wrongs against a people that lacked either the numbers or the technology to truly threaten them. Everyone in the northern hemisphere is descended from invaders like that—but we’re mostly spared the discomfort of having to look into the faces of the victims.

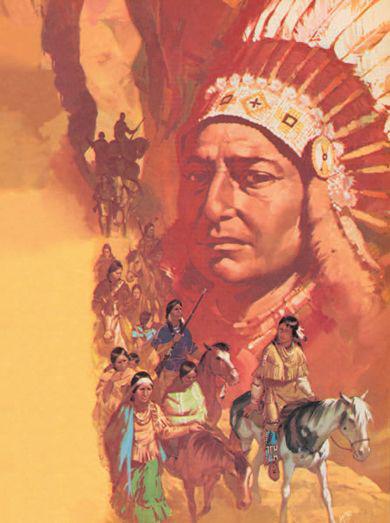

There is a photograph of Chief Joseph in the US National Archives, taken when he was still in his middle years. Like the rest of the people of the Nez Perces, he was relatively fair-skinned. The native peoples, scattered in tribal groups throughout the American continent, varied greatly in color, from almost black to a tone lighter than that of any Portuguese or Spaniard. Contrary to the Hollywood image created by the movie

The Last of the Mohicans

, for example, the men and women of that tribe were light-skinned, with mid-brown hair. The cast of the movie was composed, in the main, of members of the Sioux tribe—who bore no resemblance to real Mohicans. Also relatively fair-skinned were the people of tribes like the Blackfeet of Saskatchewan or the Pammas of Brazil.

Chief Joseph has an open face, a wide, handsome mouth and a high forehead. His chin is slightly raised for the camera, challenging. He is made instantly recognizable by the long side plaits in his hair and the style of his clothes. In the photograph he is not looking directly at the camera but off to one side, which is probably just as well. His eyes shine with an emotion that is somewhere between pride and sadness, and it looks as though it would have been hard to look him fully in the face.

His father, a chief of the Nez Perces before him, was called Old Joseph. It was Old Joseph who could more clearly remember the days when the whites were considered good neighbors. The members of the exploration party led by Lewis and Clark in the early years of the 19th century were among the first to see the Nez Perces. The encounter was a happy and peaceful one for all concerned—and especially lucky for the whites, who had been close to starvation and suffering from dysentery when they stumbled down out of the Rocky Mountains, into what would become modern-day Idaho, en route to the Pacific coast. The Nez Perces took them into their homes, fed them and cared for them until they had regained their health and strength.

Apparently the explorers noticed that some among their hosts wore jewelery, made from shells, in holes pierced through their noses. Since they had heard reports of such “pierced-noses” from the French trappers and explorers called the

coureurs de bois

—those who run in the woods—they applied the French name to this people they found living by the banks of the Clearwater River: Nez Perces. At the time of that first meeting, the Nez Perces numbered around 4,000 souls in total. They fished for salmon and, in the hunting season, made the tough crossing of the Bitterroot Mountains in search of buffalo. They were outstanding horsemen and that they kept one of the largest herds of any of the native peoples they had encountered so far.

After a few weeks, Lewis and Clark and the rest of their party were strong enough to continue on their westward adventure. A basis for warm friendship had been made, though, and for the next 70 years the Nez Perces would take pride in the fact there had never been bad blood between themselves and the whites.

But the land occupied by the Nez Perces—like every other scrap of mountain, water and valley between the two coasts of North America—fell eventually under the hungry gaze of the incomers. Old Joseph, like others of his kind, did not regard his territory as something “owned” by him or anyone else. It was just there—a self-renewing source of food, clothing and shelter. Anyone and anything was therefore free to roam across every part of it.

This was a philosophy that had had its day, however noble it may appear when viewed from today’s perspective. For all the millennia when the population of North America could be counted in terms of hundreds of thousands, or a few million, there was so much empty land that ownership of it mattered not at all; in fact it was a meaningless concept. But when the land-hungry and the dispossessed of the Old World poured into these formerly

empty places in their tens of millions, they brought a lumbering juggernaut of new thinking with them as well. In time they would find a grand name for their unstoppable advance across the land—Manifest Destiny—but in the short term it was a simple land-grab.

When in 1855 the governor of Washington Territory, a man named Isaac Stevens, told Old Joseph that he would have to limit himself and his few hundred people to a clearly defined portion of the land—and accept that the rest of the territory was now “owned” by the whites—he refused to listen. Old Joseph was just one of the chiefs among the Nez Perces, however, and although he refused to sign up to any treaty formalizing the proposed arrangement, there were others who did. As far as the US Government was concerned, therefore, all the Nez Perces had accepted the deal.

By 1863 there were more new people pressing in on the territory west of the Rockies, and hunger for the land was greater again. A new treaty was offered to the Nez Perces. This time they were to give up 90 percent of the land ceded to them by Stevens’s paper of 1855. Among other places sacred to Old Joseph, he was now expected to surrender the land of the Wallowa Valley, known to his people as the Valley of the Winding Waters. Having refused to acknowledge the legality of the 1855 treaty, Old Joseph was doubly enraged at this new proposal.

“The country was created without lines of demarcation and it is no man’s business to divide it,” he said. “Perhaps you think the Creator sent you here to dispose of us as you see fit. If I thought the Creator sent you, I might be induced to think you had a right to dispose of me. Do not misunderstand me, but understand fully with reference to my affection for the land. I never said the land was mine to do with as I choose. The one who has a right to dispose of it is the one who has created it. I claim a right to live on my land and accord you the privilege to return to yours.”

Once again, Old Joseph refused to make his mark on any paperwork. But other chiefs—strangers to the Wallowa Valley in any case—duly signed the treaty and gave away the land.

When Old Joseph died in 1871 his son replaced him as a chief. If Joseph the younger inherited anything from his father, it was the unshakable belief that no one had the right to tell him or his people where or how they might live. Like his father, he refused to acknowledge the “treaties” of 1855 and 1863, and so when white men came to tell him he must now move his people to the newly created Lapwai Reservation, he ignored them. It was a mark of the intelligence of the man, however, that he also attempted to play the white man at his own game. With a sense that he was entitled to the same legal rights as anyone else living under the protection of the President of the United States, Chief Joseph wrote to Ulysses S. Grant asking that he be allowed to continue living on the land of his ancestors. There was support for the Nez Perces among some sections of the white community, too. They, like Chief Joseph, could see the questionable legality of foisting treaties upon a people given no option but to submit. In what must have seemed like a crowning triumph, on June 16, 1873, President Grant ruled that the Wallowa Valley—the Valley of the Winding Waters so beloved by Old Joseph and all his people—belonged to the Nez Perces and was not to be colonized by any whites.

Betrayal of promises was not, however, a character weakness limited to nameless bureaucrats. Within two years of the executive order, the President decreed the Wallowa Valley open to settlement once more. Now soldiers returned to the land of the Nez Perces to tell Chief Joseph that their time was up and that they must ready themselves and their animals for the journey to the Lapwai Reservation to the north. It was 1877, the year after General George Armstrong Custer’s catastrophe at the Little Bighorn at the hands of Sioux warriors led by Sitting Bull and the legendary

Crazy Horse, and there was no love left for any of the Native Americans.

Tribes the length and breadth of the country were already suffering. The Cheyenne, the Navajo, the Sioux, the Apache, the Arapaho—all of these peoples and more had felt the harsh hand of the US Government and its military.

General Otis Howard was the soldier in charge of clearing the Nez Perces out of the Wallowa Valley, and on arrival at Lapwai he sent messengers to Chief Joseph summoning him to a meeting. Together with his most trusted comrades—his own brother Ollocot, Lean Elk, the prophet Toohoolhoolzote, White Bird and Looking Glass—Chief Joseph rode up to the reservation to try to face down the inevitable. But they arrived at Lapwai as emissaries of a world already living beyond its allotted time. What their opponents called their Manifest Destiny—their apparently divine right to rule the Americas—was just the arrival of the future in a world of the past. Chief Joseph and his men were already ghosts, haunting the living.

The meeting was ill-tempered from the start, and Toohoolhoolzote argued so bitterly with Howard that the General had him arrested and thrown into the guardhouse. He was freed once he was judged to have calmed down, and returned to the Wallowa with Chief Joseph and the others to begin the job of preparing their people for exodus. It was May, and at that time of year the livestock of the Nez Perces, horses and cattle, was scattered over many square miles. En route to Lapwai they would have to cross the Snake River, which was still running deep and fast. Despite these complications, Chief Joseph had his people on the move within a few weeks. He had considered his options and understood all too well that he lacked the numbers of fighting men needed to keep the white soldiers out of the Wallowa by force. Better, he thought, to keep everyone together and safe—and to move out of harm’s way.

He would say later:

…we could not hold our own with the white men. We were like deer. They were like grizzly bears. We had a small country. Their country was large. We were contented to let things remain as the Great Spirit Chief made them. They were not, and would change the rivers and mountains if they did not suit them.