American Eve

Authors: Paula Uruburu

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Historical, #Women

Table of Contents

CHAPTER TWO - Beautiful City of Smoke

CHAPTER FOUR - The Little Sphinx in Manhattan

CHAPTER SIX - Benevolent Vampire

CHAPTER SEVEN - Through the Looking Glass

CHAPTER EIGHT - At the Feet of Diana

CHAPTER NINE - The Barrymore Curse

CHAPTER ELEVEN - The Worst Mistake of Her Life

CHAPTER TWELVE - The “Mistress of Millions”

CHAPTER THIRTEEN - Curtains: June 25, 1906

CHAPTER FIFTEEN - Dementia Americana

CHAPTER SIXTEEN - A Woman’s Sacrifice

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN - America’s Pet Murderer

RIVERHEAD BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA • Penguin Group

(Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of

Pearson Canada Inc.) • Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England • Penguin

Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) • Penguin Group

(Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia

Group Pty Ltd) • Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi -

110 017, India • Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) • Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd,

24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices:

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Copyright © 2008 by Paula Uruburu

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned,

or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do

not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation

of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

Published simultaneously in Canada

All photographs are from the author’s collection except those on pages 16, 194, 264,

293, 364, 366, and 372, which are from the Nesbit/Thaw family archives.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Uruburu, Paula M.

American Eve : Evelyn Nesbit, Stanford White, the birth of the “It” girl, and the crime of the century /

Paula Uruburu.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN : 978-1-4406-2976-1

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers and Internet addresses at

the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors,

or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control

over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

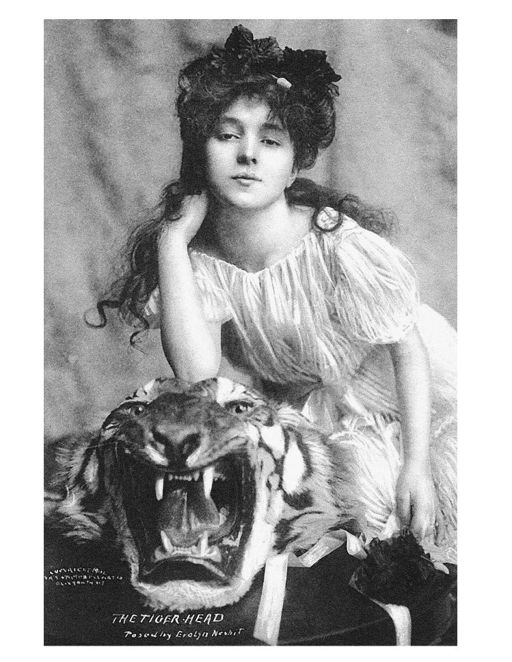

FRONTISPIECE ART:

American Eve, at sweet sixteen, posed for the Campbell Art Studio.

Come slowly, Eden!

Lips unused to thee,

Bashful, sip thy jasmines,

As the fainting bee,

Reaching late his flower,

Round her chamber hums,

Counts his nectars—enters,

And is lost in balms!

—EMILY DICKINSON

for Brian

Campbell Art Studio postcard photo

of Evelyn, 1901,

The Tiger Head.

Diana atop the Madison Square Tower, circa 1900.

INTRODUCTION

The Garden of the New World

For we must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill, the eyes of all people are upon us.

—John Winthrop, sermon, 1630

God gave me my money. . . . God has marked the American people as His chosen nation to finally lead in the regeneration of the world. This is the divine mission of America and all it holds for all the profit, all the glory, all the happiness possible to man.

—John D. Rockefeller, 1900

Rockefeller did the things that God would have done had He been rich.

—Anonymous

Nature is very cruel . . . and if civilization has overlaid us with delicacies and refinements, nature works on just as though social laws had no existence.

—Evelyn Nesbit, Prodigal Days

little more than half a century before a winsome, waiflike, and wide-eyed Evelyn Nesbit, not yet sixteen, found her way to the island of Manhattan, Nathaniel Hawthorne had written a modest allegorical tale titled “Rappaccini’s Daughter.” It is the story of an intense but immature medical student who becomes obsessed with an exquisitely lovely and innocent young woman. The girl has never ventured beyond the walls of her outlaw scientist father’s garden, a man-made paradise filled with marvelous-looking but unnatural species of fatally toxic plants and flowers. The illicit garden is the envy of a less than brilliant rival scientist, intent upon finding his way into the forbidden sanctuary and learning the secrets of his seemingly untouchable rival. Upon seeing the splendid flora and the rare beauty of the girl, the young man wonders, “Is this the Garden of the New World?” only to find out subsequently that the girl and everything in the garden are poisonous as a result of her father’s unsanctioned experiments. When he realizes he has become contaminated with the poison through exposure to the beautiful girl, the young man viciously turns on her and blames her for his condition. The girl, betrayed and brokenhearted, decides to sacrifice her life for him by releasing the poisons in her system via a lethal antidote. She dies slowly and painfully at their feet as the medical student, her father, and her father’s rival look on, respectively horrified, mystified, and triumphant.

The island of Manhattan at the turn of the last century was uncannily like Hawthorne’s fictional New World Eden. It was a walled-in, man-made wonder, filled with dazzling but lethal temptations, bitter rivalries, and dangerous secrets. It was run by a handful of powerful men, a number of whom acted with impunity outside the boundaries of conventional practices in their ruthless pursuit of both profits and pleasure. In what would prove to be a decade of overindulgence that would nearly devour itself and sink with titanic hubris only a few years later, the chosen class of calculating Calvinists who sat at the top of the food chain ruled over their classless empires of excess, believing they were blessed with “divine right.” Having reduced their methods of acquisition “to an exact science,” they amassed astonishing tax-free fortunes, lived in magnificent mansions, rode in fabulous private Pullman cars on the railroads they built and monopolized, and sailed on luxurious yachts that were themselves “floating palaces.” When asked about his yacht, the

Corsair,

J. P. Morgan replied famously, “If you have to ask how much it cost, you can’t afford it.” It was social Darwinism at its best—or worst.

By February 1900, New York’s John D. Rockefeller, the president of Standard Oil, asserted, “The growth of a large business is merely survival of the fittest, a law of Nature, and of God.” Then he crushed all his competitors into blackened viscous muck. Within a year, months before Christmas, Pittsburgh’s Andrew Carnegie gave himself an early present. He sold his interest in Carnegie Steel to New York’s J. P. Morgan for a whopping $480 million. So, while the average working stiff’s salary was slightly less than five hundred dollars a year, as the story goes, Carnegie retired on a pension of $44,000—a day.