American Eve (2 page)

Authors: Paula Uruburu

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Historical, #Women

Yet with the exception of a fistful of trust-busting politicians, certain resolute muckrakers, and the occasional enterprising anarchist, the huddled masses seemed unable to comprehend and unwilling to consider the colossal inequality between themselves and America’s staggeringly wealthy untaxed multimillionaires, men like E. H. Harriman, Russell Sage (who, it was rumored, was so cheap he didn’t wear underwear), and Henry Clay Frick, who proclaimed that “railroads are the Rembrandts of investment.” (The latter two even managed to survive violent attacks by anarchy-minded assassins.) These fittest Philistines “bought paintings like other people bought penny postcards,” and even if the Vanderbilts, Whitneys, Goulds, and their socially well-bred peers did not always know good art, they knew what they liked to buy. If they didn’t, they called upon Stanford White to decide for them.

The self-ordained purveyor and pillager of high art for America’s highest society (whose approach to art was usually either a “disheartening middle-brow indifference or a more positively demoralizing vanity”), Stanford White was the most conspicuous partner of the preeminent architectural firm of the day, McKim, Mead, and White. Like White himself, the firm grandly embraced both the public and the private. Their jewels included the Admiral Farragut Memorial; the Tiffany, Whitney, Pulitzer, and Vanderbilt mansions; St. Paul’s Church; Judson Memorial Church; the New York Herald Building; the girded wrought-iron wonder of Pennsylvania Station; and the marvelous Washington Square Arch, now New York City’s most elaborate tombstone (being located near what was a potter’s field for the indigent and then a burial ground for yellow fever victims, totaling somewhere in the neighborhood of 20,000).

Über-society impresario, aesthetic prophet, protean clubman, and all-consuming libertine, White was the creator of Manhattan’s own “Garden of the New World.” Morgan and Carnegie were two of its major share-holders (along with White himself). A block-long business and entertainment complex located at the northeast corner of Madison Avenue and Twenty-sixth Street, the Garden was an oasis of splendor situated adjacent to the formerly unassuming Madison Square. (The present-day Madison Square Garden arena, still colloquially called “the Garden,” is actually in its fourth incarnation, located between Thirty-first and Thirty-third streets and situated on top of the second Pennsylvania Station.)

Overlooking the Garden’s splendid and innovative open-air rooftop theater was its gleaming tower, modeled after the Giralda in Seville, and the tallest point (at the time) in an increasingly priapic city over which the preternaturally and passionately inspired White held sway. Topped with a gilded bronze and scandalously nude Diana, Madison Square Garden was White’s supreme architectural achievement, the envy of those who sought a coveted office or studio within its tiled and terra-cotta confines—and the site of its creator’s not so original sins, which would eventually cause him to be cut down in the shadow of the goddess. And prove his mortality. And all because of another goddess, one that was flesh and blood.

But if Manhattan at the turn into the twentieth century was a city overwhelmed by its own prosperity in some quarters, it was overpopulated with the teeming poor in others, where the bodies were less effectively hidden than those under the Washington Square Arch. It was a metropolis of mind-boggling incongruities and inequities, symbolically reflected in the proximity of Wall Street to the Battery Park seawall, beyond which stood the Statue of Liberty, and only slightly closer to New Jersey, Ellis Island. It was a city where an Astor-owned block on the Lower East Side crammed five hundred immigrant families into gruesome rat-infested tenements, regular firetraps with a death rate rivaling Calcutta’s.

In the same general vicinity stood the forbidding Tombs Prison, behind whose thick granite walls and iron bars one multimillionaire’s banjo-eyed, baby-faced son, the infamous Harry K. Thaw, would find himself for the brutal murder of the creator whose corrupted Garden stood at the roaring heart of a projected sky-scraping city he would never see. During two sensational trials that stretched over two years, with the private no longer assiduously guarded from the public, the curious crowds of ten thousand or more who mobbed the street below Thaw’s prison cell could afford to buy a souvenir penny postcard of the Tombs or the “Bridge of Sighs,” which connected the prison to the courthouse on Centre Street. Most spectators, however, scrambled to procure one of the hundred or more postcards of the murderer’s devastatingly lovely child bride and White’s former teenage mistress, the twentieth century’s American Eve and “the cause of it all.”

Much farther uptown, surrounding newly minted mansions, many designed by Stanford White and inhabited by the likes of Mrs. William Backhouse Astor (described in the newspapers as being “borne down by a terrible weight of precious stones”), there were ornate gates and formidable wrought-iron fences designed to keep out the “democrats without diamonds.” But the ordinary citizen in New York City (and those beyond its environs) was nonetheless hungry for a tantalizing glimpse into the rarefied world that existed just within those gates and behind those Garden walls. “Envious, suspicious, hopeful of sin,” the people would get what they asked for “in spades and blazing scareheads” once the murder of the century ruptured the nation’s tight-laced consciousness on a hot night in June 1906.

New York City at the turn of the twentieth century was certainly a New World paradise for some, a circumscribed fantastical Eden with its own strange walls and boundaries. Some were clearly visible; others were less obvious but no less impenetrable. Unless, of course, you were young. And beautiful.

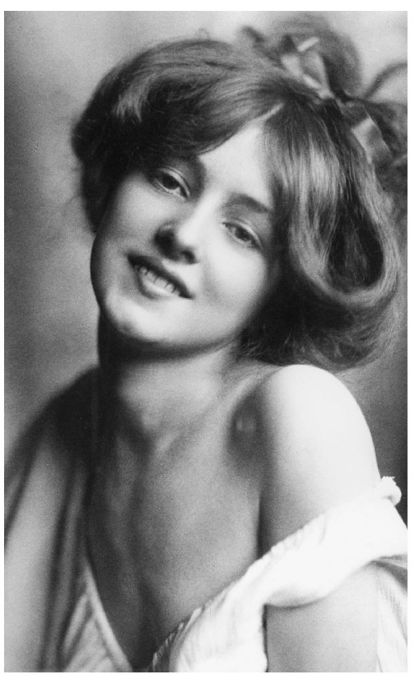

Portrait of Evelyn at age sixteen (1901), by Rudolf Eickemeyer Jr.,

that appeared in

Cosmopolitan

magazine.

CHAPTER ONE

Siren Song

She was a human camellia with something of the . . . dying beauty of the

Narcissus in her delicately-featured face.

—Newspaper clipping, 1907

She had the face of an angel and the heart of a snake.

—Augustus Saint-Gaudens

Plain girls are happiest.

—Evelyn Nesbit

The tantalizing idea of a tabula rasa—a shiny, new, unsullied century—loomed large in the collective consciousness of the majority of Americans in the final hours of 1899. The populace was precariously balanced on the razor’s edge between two antithetical worlds. One was a quickly receding past still deeply mired in the old-fashioned, the other a fast-approaching future riveted to the often hazardously newfangled, where limbs were routinely mangled or ripped out of their sockets in the grinding cogs of unfamiliar machinery, all in the name of progress. Yet while men of gilt-edged sensibilities and iron (or steel) wills forged ahead on a variety of fronts, delighted with their swift evolution, others resolutely clung to the quaint hem of Victorian virtue, identifying themselves as the defenders of the sanctity of wife and home. So even though the Sears-Roebuck catalogue in 1900 featured thirty-seven pages of accessories for horse-drawn carriages and not a single one for automobiles, the old world was fast succumbing to the new. And nowhere more emphatically and ecstatically than in “the garden spot of a spotless new century,” the city that had appeared to Whitman in an earlier manifestation as “unruly” and “self-sufficient,” whose “turbulent musical chorus” produced a perpetually mesmerizing siren song—the island its original natives had called Mannahatta.

Having emerged, however, from a series of nerve-bending depressions in the 1890s, many Americans were still struggling to simply recover and sit upright as the old century crawled steadily toward oblivion. Even a heavy dose of money offered little immunity from the unsettling apocalyptic feelings that seem to grip entire populations in the terminal phases of a dying age. But America was still naive and nubile enough on December 31, 1899, to believe in the healthy tug of renewed possibilities—despite intermittent pangs of self-doubt and an unspoken fear that the Day of Reckoning might be at hand. And even though a few of the babbling lunatic fringe indeed shouted in the streets that “the end of the world was nigh,” the

New York Times

evening edition proclaimed blithely that the nation stood poised upon the “threshold of 1900 . . . facing a still brighter dawn for human civilization.” And the average citizen agreed.

The idea of a clean, fresh slate certainly seemed infectious. And nowhere was there such a splendidly contagious sense of unreality and invincibility as the glowing metropolitan island where almost no one and nothing was ever average. For the extraordinary occasion, the city’s most superbly unruly son, Stanford White, turned Madison Square Park into an marvelous fairyland with more than 3,000 miniature orange-hued Chinese paper lanterns hung on every available post and branch. The anticipation of a new millennium was absolutely electric as the last minutes of the withering 1800s hung suspended in the frigid air, overripe and ready to drop.

And then midnight erupted. The Venetian plaster was barely dry in the uptown Fifth Avenue fiefdom where “the Four Hundred” popped Pommery Sec corks and toasted the new year from Mrs. Astor’s exclusive ballroom on high. Meanwhile, in the lower reaches of Mott Street and below Canal Street, the less refined fired off revolvers into the blue-black sky, unconcerned in their soused serf revelry as to where the bullets might land (two were killed and three wounded, according to the newspapers the next day). That night, in the choppy waters surrounding the island, Standard Oil’s omnipresent tugboats sounded their horns, while the intermittent hooting blast of steam whistles from the ferries rippled joyfully across both the Hudson and East rivers. Snow flurries had begun to fall just before midnight, softening the effects of bone-chilling darkness. Illuminated in shimmering, spidery staccato bursts and explosive flashes by a barrage of Chinatown fireworks set off exactly at midnight near the Brooklyn Bridge, the wayward flakes flickered and pinwheeled like multicolored confetti. It was as if God Himself had joined the celebration.

The “loads of babies given up to the streets of the Bowery” who had waited impatiently for the signal, blew excitedly into lead-painted tin penny whistles. Gaggles of frowsy women clanged and banged on iron skillets and pots with metal spoons from the stoops of swarming tenements. Thin-legged feral street Arabs blew across the mouths of empty bottles of rotgut they found in the alleyways they slept in, imitating the tugboat horns in the distance and becoming giddy and light-headed from the alcoholic fumes.

The

New York World

announced the next morning that the 1800s were gone forever, replaced by a “brisk, bright, fresh, altogether new 1900 . . . good for a clean one hundred years. . . .” That same morning, from the White House, the new century’s first president, William McKinley, who embodied the nation’s self-satisfied and slightly overblown sense of indestructibility, issued his New Year’s statement of good cheer, wished the electorate well, then went back to bed, exhausted from hours of endless handshaking at several balls the night before (a practice he had been advised to curtail for reasons of personal security). That same night, in Philadelphia, an exhausted and exceptionally striking young artists’ model, who the papers said had “taken the studios by stormy steamy surprise” a year earlier, slept through the noisy celebrations around her in the streets and saloons, unaware that she was destined to “rock civilization” with her own siren song within a matter of years and sink an entire gilded class in the whole bloody process.

Seemingly overnight, the inhabitants of the brash and volatile island of Manhattan had already set the mood for their new century and the rest of the country—one of unrepentant self-absorption—but, typically, with little self-reflection. Amid the mirth and merriment, in the established tradition of American mythmaking, Gothamites also believed themselves to be self-made and self-sustaining. As such, some of the citizens seemed to adopt instantaneously a carpe diem attitude, which provided a convenient solution to the dilemma of dwelling on past sins they would nonetheless be doomed to repeat. Others, soaked in the spirit of change, embraced the dawn with both arms and plotted their heady campaigns for advancement. For many, the stuffy waltzlike circularity of the past was already being displaced with rousing Sousa marches or the audacious open-ended ragtime riffs of the “newest American Negro music.” But the “barbaric harmonies” and dangerously diverting offbeat rhythms of ragtime shocked the whitest-bred decent majority. Perhaps there were a discriminating few within the rollicking mob who heard the imminent rumblings of political, economic, and social revolution that New Year’s Day. If so, only a handful cared to listen, surrounded as they were by Mannahatta’s deceptively jubilant dissonance and “turbulent musical chorus.” The rest of the population, it seemed, was easily distracted. And easily seduced.