American Eve (22 page)

Authors: Paula Uruburu

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Historical, #Women

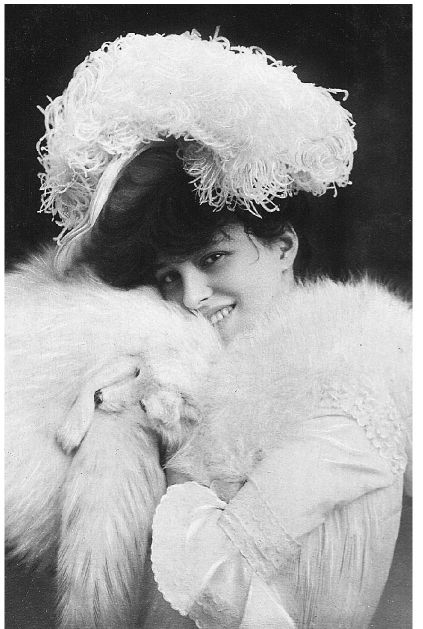

Evelyn as Vashti, the Gypsy girl, with

another chorus girl in

The Wild Rose,

1902.

of “paddling her own canoe” and “not only opening doors herself, but turning the heads of seasoned theatrical managers on her own.” The extent of her acting talents, however, remained a question.

As it had with her modeling career, the publicity machine began working overtime once Evelyn began her run in

The Wild Rose.

A two-page article, which appeared in the centerfold of the

New York Herald

on May 4, 1902, told the story of the budding Broadway beauty and gave the details of her unique contract for

The Wild Rose

company. Its headline read, “Her Winsome Face to Be Seen Only from 8 to 11 p.m.” This was accompanied by drawings and photos of “Miss Evelyn Florence in Various Poses.”

Beginning first by examining the business end of show business, the article described how “rare loveliness in young womanhood is apparently a strikingly valuable asset in the inventories of theatrical managers whose productions depend for their success to a large extent on their possession of good-looking, shapely and graceful girls. . . . Only a few seasons ago only featured players were signed to exclusive contracts. Now a well-known purveyor of feminine loveliness has signed a new beauty whom he recently discovered to such a contract. This agreement has Manager George Lederer as party of the first part and Miss Evelyn Florence as its collateral subject.”

This unique piece, a new type of public relations, and the so-called actual stipulations of Evelyn’s contract would be quoted again when Evelyn made her first appearance in the July 1902 issue of

The Theatre

magazine. Unlike other chorus girls, who were destined to remain anonymous or relatively unknown (and certainly never would have their photos appear in such a prestigious and influential magazine, let alone occupy so much space), Evelyn was featured in two photos and would appear in another issue several months later (see page 127).

Articles began to appear with regularity, focused on Evelyn’s budding Broadway career and filled with full-page photographs or drawings of the model-turned-actress Evelyn Florence (or Evelyn Nesbit or Evelyn Nesbitt). Each article sought a new angle for promoting this “fresh and fascinating theatrical find.” One headline raised the question of whether Prince Henry of Belgium would have married the young British society girl he did marry, a Miss Dolan, had he seen “this American Girl.”

ONE-NIGHT STAND IN NEWPORT (AUGUST 25, 1902)

As far as the press was concerned, a particularly newsworthy story involving Evelyn emerged when, in August 1902, it was announced that Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt, one of White’s clients (and perhaps at his suggestion) , had hired the entire company of

The Wild Rose

and its orchestra to perform at the fabulous “cottage” in Newport named Beaulieu, which White had designed for her. The papers reported that the “hundred or so citizens of lower Broadway were to entertain the 400” at Beaulieu and proclaimed cheerfully that, “Real Darkies Will Also Give a Genuine Cakewalk.”

With the exception of two cast members and their well-known manager, the company from

The Wild Rose,

as well as “a troupe of nine Negroes engaged by the Lederer amusement company” were to set sail for Newport. Lederer did not accompany his players, feeling his presence was needed at the rehearsals of his new piece,

Sally in Our Alley,

at the Broadway Theatre, so his brother, James, went in his place.

The papers seemed as intrigued by this curious adventure as if it were an authentic savage safari, except clearly the view was that the unruly natives were the ones invading the little Rhode Island haven of civilization carved out of pink-and-white Italian marble. It was advertised that “Negroes will play in a pagoda erected in the theater for their accommodation and concealment, and “Williams and Walker will sing ‘When Sousa Comes to Coon Town’ and ‘The Coon with the Panama’ ” (referring to the cigar). All of this, of course, was perfectly in keeping with the attitude of the age, in which tourists from Hoboken and the Bronx could see actual Zulu warriors “on display” at Coney Island in the same vicinity as the “Fairy Floss” concession stand, and an “honest-to-goodness Eskimo family” was camped on the boardwalk next to live babies in a new invention called an incubator.

It was also considered newsworthy that “Miss Mazie Follete and Evelyn Florence Nesbit who had expected under proper chaperonage to make the trip to Newport aboard the private yacht of a wealthy friend did not realize their expectations and took the plebeian route.” “Miss Nesbit however was accompanied to the pier by a young man who if not the proprietor of a yacht certainly looked the part and dutifully toted the suitcase of the diminutive Evelyn.” According to the story, although Evelyn was satisfied with her accommodations, Mazie Follete complained that she wanted a larger room with a bath, as her people suffer from a hereditary disease, a

“mal de mer.”

STANNY CLAUS

For Evelyn’s seventeenth birthday, on the day before Christmas Eve 1901 (since, as she knew, her paramour would be spending the holidays with his family), a jolly Stanny turned his Garden Tower room into a wonderland, a veritable hothouse of flowers, even though it was December. There were American beauty roses, long-stemmed calla lilies, milky white gardenias, mauve and purple and green and yellow orchids, the largest number of hydrangeas she ever saw, and potted holly bushes placed around the room in splendid variations of color. To add to the effect, Stanny had sprinkled confectioner’s sugar on all the blooms to simulate snow.

He sat Evelyn on one of the divans and told her to close her eyes. Then, for the little girl who had to pretend she had been given a stray cat as her only gift a few shabby Christmases ago, Stanny produced from behind his back an oversized red velvet stocking with “a lovely large pearl on a platinum chain . . . a set of white fox furs which were a novelty at the time . . . a ruby and diamond ring and two diamond solitaire rings.” She jumped from the sofa and draped the furs around her shoulders, twirling and laughing, then kissing his hands and the tips of his fingers in appreciation. She teased him and called him “Stanny Claus” (a much better model than the stiffly tedious James Garland). Stanny told her she would have to be photographed with her furs and also laughed, perhaps imagining what kinds of artful arrangement he could achieve with such elegant props and his little Galatea.

True to his nature of never doing anything by half, as the weeks passed, Stanny continued to spend an immoderate amount of money he didn’t really have on Kittens (and her mother and brother) in his acknowledged public role as patron and paternal protector. He had, for all intents and purposes, become Howard’s father, a consequence of which was that

Postcard photograph of Evelyn wearing

Stanny’s gift of white fox furs, 1902.

Stanny’s secretary, who handled all of White’s personal financial transactions, had also developed a relationship with young Howard that some suspected was of too intimate a nature, given the additional speculation that White’s secretary was one of “Nature’s bachelors.”

In spite of his myriad professional obligations, Stanny made sure that Evelyn didn’t suffer from lack of work in terms of theatrical auditions; she made brief appearances in such shows as

A Chinese Honeymoon

and

Under Two Flags,

even though the steady demand of modeling assignments for artists, illustrators, and photographers often pushed her fledgling acting career into the shadows, much to her dismay. On those glorious days when Evelyn was actually free from any kind of professional commitment, however, Stanny continued to take discernible pleasure in orchestrating her social calendar, filling her days with lighthearted distractions. There were steamboat excursions to Rye and Oakland beaches in Westchester across the Long Island Sound and picnics in Central Park, raucous outings to Coney Island to ride the Razzle Dazzle and only slightly more sedate evenings at the newly built and hypnotically incandescent Luna Park—all on Stanny’s tab and always with a flock of other girls—but never, ever with Stanny.

Yet, while they were not exactly Svengali and Trilby, the master show-man maintained a mesmerizing hold on his little dolly, even as Evelyn grew increasingly restless, weary of keeping secrets and being kept in the dark as one of them. She felt, every so often, a slow, dull, binding ache in her abdomen and attributed it to being trussed up in costume corsets, an occupational hazard, since she never wore one otherwise. But as the days continued to tip over nonchalantly into weeks, the wild rose began to wish intensely for some control over her own destiny. Or, at the very least, for selective amnesia.

White’s impossibly hectic schedule made togetherness either physical or otherwise with Evelyn progressively more difficult, even after hours, when the protective cloak of darkness draped itself over Manhattan (the only time in any day Evelyn had come to believe was hers and Stanny’s alone). Like a frantic vaudeville plate spinner always on the brink of losing control, White dashed back and forth between Broadway and his grand house, Box Hill, in St. James, Long Island, or between Fifth Avenue and somewhere on the Continent, tending to family obligations, overseeing a staggering multitude of projects (up to sixty at a time), cabling, cajoling, creating, and carousing—and secretly wavering on the brink of a personal financial crash.

But after months of clandestine coupling with the inexhaustible master designer, letting her heart fall into and then languish in his gifted but careless hands, Evelyn began to feel that she and Stanny had reached a kind of impasse. She knew he still cared for her, which she said later in life was not the same as love, “a slightly larger word than sex and therein lies the difference.” And in spite of all the mooning popular songs about the subject, “Love with a capital L,” Evelyn would come to believe, “could be a merciless word.”

For her part, having misspent her “mossy rose” and squandered real affection on the ultimate fake fakir (whose feats of endurance continued to mystify and entertain his cult of co-conspirators), Evelyn was still an adorable fixture at the usual nocturnal Madison Square Garden revels. But if she began to feel that she had become just another lovely object to Stanny, desperately sought and despicably won, a prized possession increasingly neglected among an excess of superb acquisitions, she did not say so. Like a dark-haired diminutive Rapunzel trapped by fantastic circumstances in a magical Tower, she remained a kept girl, waiting for a princely rescue and the healing tears of happily ever after. In a weird way, all the elements of the Grimms’ tale (which she had read back in Tarentum) were in place—the uncommon changeling child-woman, the hard bargaining, forbidden fruit, and feminine wiles. The only thing missing was the unseen watcher. Or so it seemed.

Dashing Jack Barrymore in a postcard

photograph, circa 1902.

CHAPTER NINE

The Barrymore Curse

“Could You Be True to Eyes of Blue If You Looked into Eyes of Brown?”

—Song title, 1901

“If Money Talks It Ain’t on Speaking Terms with Me”

—Song title, 1902

As far as Evelyn could tell, she was Stanny’s “one and only special dolly.” But even as their furtive Dionysian relationship carried on with a kind of uncontrived momentum, White also continued to befriend and (in Evelyn’s darkening eyes) be overly friendly with an unhealthy number of other young soubrettes. From Adora Andrews to Erminie Earle, Hilda Spong to Augusta True, Stanny’s generosity ran the gamut from A to Z (and back again) as he paid for hospital or dental bills and sometimes rent and wrote affectionate notes and the like, which Evelyn didn’t appreciate at all. Evelyn wrote Stanny her own love letters during a weeklong seaside holiday he had arranged for her in the sleepy south shore community of Freeport, Long Island. She wrote him every day from her hotel room and kept his responses in a silk-lined tufted pink jewelry box, already stuffed with expensive hatpins from Tiffany, a small hand-painted compact full of fashionable faux beauty marks, and theatrical baubles bought on lower Broadway.