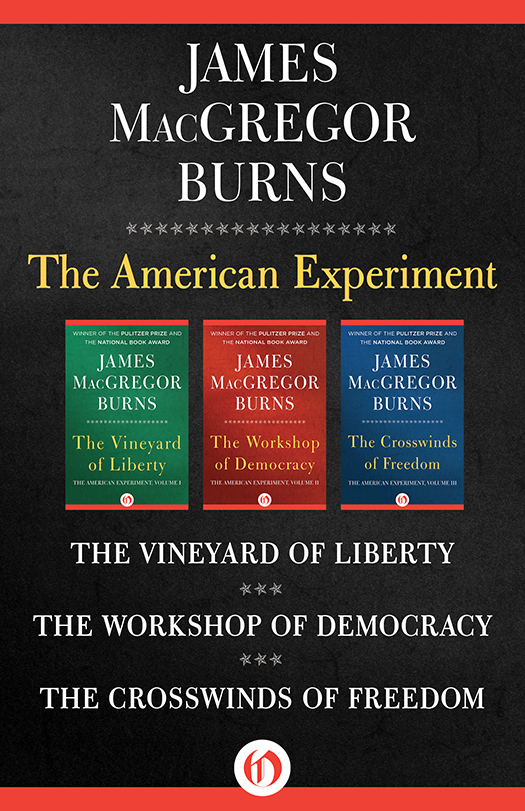

American Experiment (286 page)

Read American Experiment Online

Authors: James MacGregor Burns

Any errors or deficiencies are solely my responsibility—and I would appreciate being informed of them, at Williams College, Williamstown, Mass. 01267. I wish to thank those who sent in corrections for the first volume. They were: (p. 116) Benjamin Franklin lay mortally ill at this time rather than “lay dying,” as he did not die until a year later; (180) it was not Lewis but Clark who had probably met Daniel Boone; (501) Whittier was a Quaker, not a Unitarian (though he did have Unitarian sympathies); (518) Lovejoy was the son of a Congregational minister, not a Presbyterian one, he was a student at Princeton Theological Seminary but did not graduate from it, and he might better be described as an “extremist” than as a “fanatic.” These changes have been made in the paperback edition (1983).

As with the first volume, I have borrowed occasional phrases or sentences from my own earlier works in cases where I felt my prose was—or should be made—imperishable.

J.M.B.

The American Experiment, Volume III

James MacGregor Burns

TO WRITERS FOR THE THIRD CENTURY

Deborah Burns

Stewart Burns

Milton Djuric

Peter Meyers

Trienah Meyers

Wendy Severinghaus

Jeffrey P. Trout

PART I • What Kind of Freedom?

CHAPTER 1

The Crisis of Leadership

“DISCIPLINE AND DIRECTION UNDER LEADERSHIP”?

“LENIN OR CHRIST” OR A PATH BETWEEN?

CHAPTER 3

The Crisis of Majority Rule

COURT-PACKING: THE SWITCH IN TIME

CONGRESS-PURGING: THE BROKEN SPELL

PART II • Strategies of Freedom

THE RAINBOW COALITION EMBATTLED

CHAPTER 5

Cold War: The Fearful Giants

THE DEATH AND LIFE OF FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT

CHAPTER 6

The Imperium of Freedom

CHAPTER 7

The Free and the Unfree

PART III • Liberation Struggles

CHAPTER 8

Striding Toward Freedom

CHAPTER 9

The World Turned Upside Down

CHAPTER 10

Liberty, Equality, Sisterhood

BREAKING THROUGH THE SILKEN CURTAIN

PART IV • The Crosswinds of Freedom

CHAPTER 11

Prime Time: Peking and Moscow

FOREIGN POLICY: THE FALTERING EXPERIMENTS

CHAPTER 13

The Culture of the Workshop

PART V • The Rebirth of Freedom?

CHAPTER 14

The Kaleidoscope of Thought

KINESIS: THE SOUTHERN CALIFORNIANS

CHAPTER 15

The Decline of Leadership

REPUBLICANS: WAITING FOR MR. RIGHT

REALIGNMENT? WAITING FOR LEFTY

MEMORIES OF THE FUTURE: A PERSONAL EPILOGUE

We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor. It must be demanded by the oppressed. Frankly, I have yet to engage in a direct-action campaign that was “well-timed” in the view of those who have not suffered unduly from the disease of segregation.

For years now I have heard the word “Wait!” It rings in the ear of every Negro with piercing familiarity.… We have waited for more than 340 years for our constitutional and God-given rights. The nations of Asia and Africa are moving with jetlike speed toward gaining political independence, but we still creep at horse-and-buggy pace toward gaining a cup of coffee.…

We will reach the goal of freedom in Birmingham and all over the nation, because the goal of America is freedom.

PART IMartin Luther King, Jr.

Letter from Birmingham Jail

April 16, 1963

What Kind of Freedom?

CHAPTER 1

The Crisis of Leadership

S

LOWLY GAINING SPEED, THE

glistening Ford Trimotor bumped across the grassy Albany airfield and nosed up into lowering clouds. It was July 2, 1932. The day before, the Democrats, meeting in Chicago, had nominated Franklin D. Roosevelt for President of the United States. Roosevelt and his family had received the news in their Hyde Park mansion after long hours in front of the radio listening to the bombastic speeches charged with hatred for Hoover Republicans and all their works. At the moment of greatest suspense the Roosevelt forces had gone over the top.

As the plane turned west Roosevelt had a chance to glimpse the Hudson, the river of American politics. With his twinkling pince-nez, his cockily uptilted cigarette holder, his double-breasted suit stretched across his big torso, his cheery, mobile features, he radiated exuberant self-confidence and a beguiling self-esteem as he leafed through a pile of congratulatory telegrams. He had long planned this little stroke of innovative leadership— to accept the nomination in person instead of awaiting a pompous notification weeks later. He was the first presidential candidate to fly; perhaps it was a tonic to this vigorous man, crippled since 1921 by polio, to demonstrate his mobility at the climactic hour. In any event, he could have fun with the press.

“I may go out by submarine to escape being followed by you men,” he had twitted the reporters. Or he might ride out on a bicycle built for five. “Papa could sit in front and steer and my four sons could sit behind.”

Part of his family was flying with him—his wife, Eleanor, and sons Elliott and John—along with counselor Samuel Rosenman, secretaries “Missy” LeHand and Grace Tully, and two state troopers as bodyguards. The rest of the family and Louis Howe, his longtime political confidant and aide, awaited the plane in Chicago. Eleanor Roosevelt, pressed by reporters, was staying in the background. “One person in politics is sufficient for one family,” she had said the night before, while instructing the butler to bring frankfurters for the gathering. “I’ll do as I’ve always done, accompany my husband on his trips and help in any way I can.”

The plane pounded on, following the route of the old Erie Canal—the

thin artery that had pumped people and goods into Buffalo and points west, and farm produce back to the East. Now an economic blight lay across the land. For a time Roosevelt watched the deceptively lush fields unfold below; then he turned to Rosenman. They had work to do—trimming and polishing the acceptance speech. Over the radio came reports of the restive delegates in Chicago. Some were starting home. The disgruntled men of Tammany, sore over Al Smith’s defeat, were planning to be gone before Roosevelt arrived. Convention managers were trying to enliven the delegates with songs and celebrities. On the plane Roosevelt and Rosenman huddled over the speech. It had to galvanize the weary delegates, the whole weary nation.

As buffeting winds pushed the plane far behind schedule, the two men lopped more and more paragraphs off the draft. Roosevelt had no time for the crowds that gathered at the refueling stops in Buffalo and Cleveland. While John was quietly sick in the rear of the plane, his father passed pages of his draft to Elliott and Eleanor, chain-smoked, joked with his family, and slept. When the plane touched down hours later in Chicago, Roosevelt boasted, “I was a good sailor,” as he greeted his oldest child, Anna, and sons James and Franklin.

The airport scene was chaotic. Crowds pressed in around the candidate, knocking off his hat and leaving his glasses askew. Campaign manager James Farley pushed through to Roosevelt. “Jim, old pal—put it right there—great work!” Louis Howe was his usual dour self. Climbing into the candidate’s car with him, Howe dismissed the Roosevelt and Rosenman draft, which had been telephoned to him the night before. Rosenman, forewarned of Howe’s attitude, made his way through the throng to the candidate’s car, only to hear Howe saying, as he thrust his own draft into Roosevelt’s hand, “I tell you it’s all right, Franklin. It’s much better than the speech you’ve got now—and you can read it while you’re driving down to the convention hall, and get familiar with it.”

“But, Louis,” Rosenman heard his boss say, “you know I can’t deliver a speech that I’ve never done any work on myself, and that I’ve never even read.…” When Howe persisted, Roosevelt agreed to look it over. As his car moved through big crowds to the stadium, he lifted his hat and shouted “hellos” left and right, pausing to glance at Howe’s prose. Finding Howe’s opening paragraphs not radically different from his own draft, he put them on top of it.

Waiting at the Chicago Stadium, amid ankle-deep litter and half-eaten hot dogs, amid posters of FDR and discarded placards of his bested foes, amid the smoke and stink of a people’s conclave, were the delegates in all their variety and contrariety—Louisiana populists and Brooklyn pols,

California radicals and Mississippi racists, Pittsburgh laborites and Philadelphia lawyers, Boston businessmen and Texas oilmen. The crowd stirred, then erupted in pandemonium, as Roosevelt, resplendent in a blue suit with a red rose, made his way stiffly across the platform on a son’s arm, steadied himself at the podium. He looked up at the roaring crowd.

He plunged at once into his theme—leadership, the bankrupt conservative leadership of the Republican party, the ascendant liberal leadership of the “Democracy.” After a tribute to the “great indomitable, unquenchable, progressive soul of our Commander-in-Chief, Woodrow Wilson,” he declared that he accepted the 1932 party platform “100 per cent.”