American Gun: A History of the U.S. In Ten Firearms (13 page)

Read American Gun: A History of the U.S. In Ten Firearms Online

Authors: Chris Kyle,William Doyle

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction

At First National, Bob and Emmett grabbed a hostage and escaped through a back door. They promptly shot and killed a man who happened to be passing by.

“You hold the bag, I’ll do the fighting,” Bob told his brother as they headed around the corner back toward the horses. “Go slow. I can whip the whole damn town!”

For a few dozen paces, it looked like he could. Bob walked along calmly, snapping his fingers and whistling. Gunfire began dropping civilians. The injured were pulled into Isham’s hardware shop, and soon the store resembled a blood-soaked hospital emergency room.

An unsuspecting boy wandered into the path of the robbers, one of whom shoved him aside with the warning, “Keep away from here, bud, or you’ll get hurt.”

Grat, Broadwell, and Power were now dead. The two other Daltons made it to the alley where their horses were, and if luck or maybe a convenient road detour were on their side, they might just have made it out. But luck wasn’t something they had much of that day, and the citizens’ superior numbers began to tell.

Depending on the model and caliber, the Winchesters the town was armed with fed as many as fifteen bullets through a round tube magazine into the breech. Pull down on the trigger guard, come back up with it, fire—even if most of these folks hadn’t grown up around guns all their lives, they still would have had no trouble learning how to fire the rifle in the heat of the battle. The front sight was fixed, and while the rear could be adjusted, my suspicion is that at close range the good citizens of Coffeyville didn’t have to do much messing around with the sight.

One by one, the Dalton boys were shot to pieces. Emmett made it to his horse, but Bob staggered and fell, finally perforated to the point where he couldn’t go on.

“Good-bye,” Bob told his brother as Emmett tried to pull him to safety. “Don’t surrender, die game.”

Emmett might have obliged, but he was hit several times and settled to the dust. There he was grabbed and dragged into the office of a local Dr. Welles. The doctor had taken an oath to preserve life, but as a good part of the town crowded in, he realized they were fixin’ to apply their own medicine to his patient with the short end of a rope.

“No use, boys. He will die anyway,” he told the crowd.

“Doc, Doc, are you certain?” someone asked.

“Hell, yes, he’ll die,” said the doctor. “Did you ever hear of a patient of mine getting well?”

The mob laughed, then ran off to gawk at the four robbers who hadn’t the luck to make it to Doc Wells’ office alive.

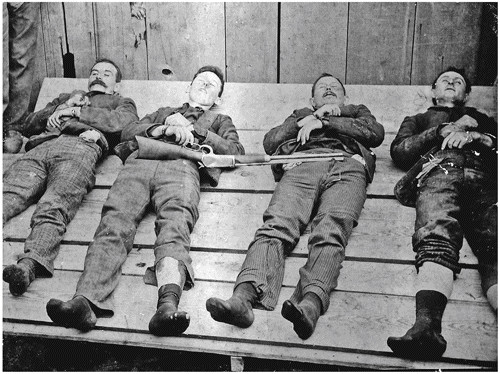

The four were about as dead as men can get. One was said to have “as many holes in him as a colander,” and another report estimated twenty-three pieces of lead in one of the bodies. The town had saved its money and earned a place in history, though it had paid a steep price: Four civilians were dead.

The Dalton Gang pose with a Winchester.

The deceased robbers were propped up for a picture, with a Winchester draped across them. Some dumb ass figured out that if you moved the dead Grat Dalton’s arm up and down, blood flowed out of a prominent hole in his throat; quite a number of people amused themselves trying it.

Contrary to the doctor’s assessments of his skills, Emmett survived almost two dozen gunshot wounds and wound up in jail. Sentenced to life, he turned over a new leaf and was freed after serving some fourteen and a half years. Freed, he became an actor and a writer, somewhat less dangerous activities than robbing banks, though in some eyes nearly as dubious.

The Coffeyville battle is a great action story, probably as exciting to hear and tell today as it was a hundred-some years ago. But it wasn’t just the bullet slinging that makes it stand out from a historical point of view. In deciding to stop the robbery, the citizens had drawn a big red line not in the sand, but across the West. The country was to be wild no more. Law and order would prevail. Not only were Americans taming the West, they were taming themselves.

And if the people in the West had evolved, so had the guns they used to instill order on the chaos of nature and themselves. The Winchesters used in the Coffeyville battle represented a climactic moment in the century-long evolution of American frontier rifles.

The Winchesters were never commonly used as combat weapons by American military forces. There were a bunch of reasons, from head-shed (aka top brass) prejudice against repeaters to the difficulty of cycling rounds while lying flat behind thin cover. Instead, the repeater became the all-purpose working rifle for countless thousands of cowboys, ranchers, lawmen, and homesteaders for the last quarter of the nineteenth century.

Protecting the Herd

, by Frederic Remington. Winchesters were standard issue for cowboys and ranchers.

Library of Congress

I love lever-action rifles. I have since I was old enough to chase my little brother, Jeff, around the family house playing cowboys and lawmen. As a matter of fact, I lusted after his Marlin .30-30 when we were kids. I had a fine bolt-action .30-06, but his lever-action Marlin looked to me like a cowboy gun, and in my mind that made it the best.

The whole idea of a lever-action rifle is to slip a cartridge into the breech quickly and easily, so it can then be put to good use by pulling the trigger. The trigger-guard mechanism on the outside of the gun works a lever that pushes the spent cartridge out of the breech when it’s pulled down. Sliding the lever back up snugs a fresh one into place. The inside cogs and springs of the action that get this done are tucked out of sight, of course; all the operator sees and feels is a very satisfying click-click that shouts WILD WEST in capital letters.

The Spencer had been the most successful repeater of the Civil War era, but even so, it did have limitations. The operation came to a full stop after the cartridge was chambered. Before the bullet could fly, the shooter had to pull back the hammer manually, usually with his thumb. Only then was the gun ready to fire.

Wouldn’t it be easier, someone thought, if you could use the same lever that was getting the bullet in place to ready the hammer as well?

Actually, you could. And while it may not seem like that big a deal to someone used to a Spencer, or other weapons of the day, that little touch of simplicity made for a much smoother and quicker shooting process.

As it happens, someone had thought of this setup well before the Spencer reached Gettysburg. The Henry Repeater, such as the model Lincoln tested in 1861, used just such an arrangement. The weapon had other shortcomings, but the ideas behind its action were solid.

In the late 1860s, Oliver Winchester purchased the remains of the company that created the Spencer Repeater. One of the reasons he had the cash to do so was the success of his firm, now known as Winchester Repeating Arms Company. Winchester and company had stayed with the basic design of the Henry, but made so many improvements that the Winchester Model 1866 was really a very different animal. True, it had a bronze-alloy frame like the Henry, and it still used the same rim-fire cartridge. But where the Henry had been more than a tad on the temperamental side, the 1866 was a robust shooting iron. Its red brass or gunmetal receiver had a yellowish tint to it, earning it the nickname “Yellow Boy.” But there wasn’t anything yellow about it. The magazine was sealed. You could load the weapon at the side thanks to a loading gate. There were a bunch of other little improvements that helped the gun stand up to the strains of the frontier.

But it was the company’s next rifle, Model 1873, that earned Winchester its everlasting fame. Again, this was a sturdy weapon, even more so than the 1866. It also used a .44–40 cartridge. This gave the gun more stopping power, while not being so large that it made the rifle hard to handle. It also meant you could use the same ammo in your rifle and Colt Frontier revolver. The Winchester found a sweet spot where power, convenience, and versatility were in perfect balance.

The search for a perfect weapon had been a long, dusty trail, with a number of detours and missteps. It produced some mighty fine weapons, even if none were “perfect.” The ideal weapon depends on the circumstances you find yourself in. Sometimes you want a lot of bullets. Sometimes you want just one big one.

Size did matter on the Plains. American settlers surged westward from the eastern forests and quickly discovered that the original flintlock American long rifles with a .32-caliber ball weren’t powerful and fast-loading enough for the larger game out West. Buffalo, elk, bighorn sheep, grizzly bear, and mountain lion all required guns with bigger loads. And unless you were a skilled contortionist, the American long rifle was pretty awkward to carry and use from the saddle.

So new single-shot, muzzle-loading hunting rifles came on the scene. The most famous Plains rifle was a model made by the Hawken brothers, gunsmiths in St. Louis, Missouri. The Hawkens cut the barrel down to thirty inches, and boosted the projectile to at least .50 caliber. That gave their weapons the power to knock down big animals at long range. On the wide-open plains, accuracy at distance was essential, due to the fact that it was difficult to sneak up on anything. The weapon became a favorite among hunters, trappers, mountain men, traders, and explorers, first as a flintlock and then as a percussion cap gun after 1835. The Hawkens called them “Rocky Mountain Rifles.”

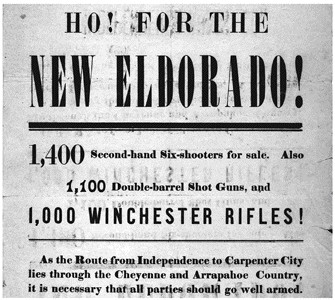

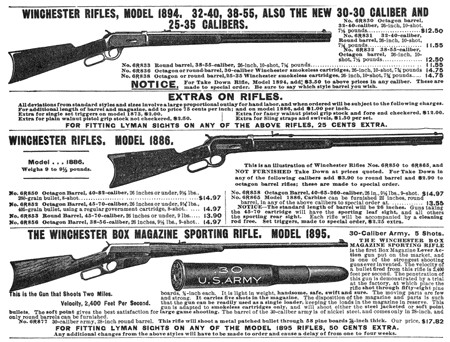

Above: An 1879 broadside boasting its advertiser’s stock of Winchesters to settlers and travelers headed into Indian country. Below: A later Sears and Roebuck ad hawking the latest models.

Library of Congress

But the big daddy of all Plains rifles was the post–Civil War “Sharps Big 50,” the quintessential powerhouse buffalo gun. This piece contributed directly to the shaping of America by powering the final expansion of European settlers across the continent. Its bullets slaughtered millions of buffalo. The consequences were complex and, for Indians as well as the animals, not very pleasant, but the weapon itself was a fine piece of work.

The large-caliber Sharps built on the design and reputation of the single-shot, breech-loading, falling-block Sharps rifle, which had done so well on the field of battle during the Civil War. The new model had center-fire metallic cartridges and a half-inch-diameter projectile. It retained its vertical dropping-block action, which was operated by the trigger guard. The action was not only strong but limited the release of gases when the gun was discharged. The thirty-inch barrel had eight sides, which was not uncommon at the time. I don’t know if that made it stronger or just easier to build, but it did give the weapon a special feel.