American Gun: A History of the U.S. In Ten Firearms (17 page)

Read American Gun: A History of the U.S. In Ten Firearms Online

Authors: Chris Kyle,William Doyle

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction

After the Revolution, the ordnance bureaucrats ignored the obvious promise of the breech-loading rifle and percussion cap and forced the military to cling to outdated muzzleloaders and flintlocks into the Mexican War era and beyond. During the Civil War, breechloaders, repeaters, and Gatling Guns were available for mass production and might have won the war for the Union much more quickly, but officials stubbornly sidetracked each breakthrough.

In the Indian Wars, they kept Winchester repeaters out of our troops’ hands. Incredibly, after the Little Bighorn disaster, Army Chief of Ordnance Stephen Vincent Benét insisted that the totally obsolete single-shot Trapdoor Springfield would remain in service as the regulation infantry shoulder weapon from 1874 to 1891. His successor, Daniel Webster Flagler, chose the Krag-Jorgensen to replace the Springfield Trapdoor over the Mauser. Why? Partly because the boob-ureaucracy thought the Krag would use less ammunition and so reduce costs. These guys had a fatal fetish for conserving ammo. I’m all for cutting back on government waste, but there’s a point where saving money ends up costing a heck of a lot more in people’s lives. The Ordnance officers flew past that point time and again.

Privately, many U.S. Army officials were horrified by the carnage wreaked by the superior firepower of the Mauser rifles at the Battle of San Juan Heights. They were determined to get their soldiers a much better gun than the Krag. Captured Spanish Mausers were carefully analyzed, and gradually an idea began to spread:

“Why not just copy the Mauser?”

And so they did.

Developed from earlier Mauser designs, the Mauser M93 used on Cuba stands at the head of a family of weapons that saw rapid improvement in the years around the turn of the century. As you’d expect, the rifle’s development and innovations in ammunition went hand in hand. Advances in the science of alloys led to stronger steel and more powerful and lighter weapons. That meant that other improvements in powder could be put to work. Cartridges could be more powerful without damaging the weapon. Bullets could go faster and farther.

The Mausers used what is known as “bolt action” to handle the complicated business of putting the ammo in place and then sending it on its way. The breech of a bolt-action rifle is opened by a handle at the side of weapon. When that handle is drawn back, the spent cartridge is ejected. The handle is then pushed forward, stripping the cartridge from the magazine and placing it into the chamber. The bolt is locked in position, and the gun is ready to fire. It’s tough to improve on this system—most of my sniper rifles were bolt-action.

Going from black to smokeless powder didn’t just make it easier to see on the battlefield. Rifle bullets could now move faster and go farther with the same or even less volume of powder. The design of the bullets and their cartridge evolved hand in glove with the powder and the rifles, becoming more efficient and cleaner in the gun.

Not to mention deadlier.

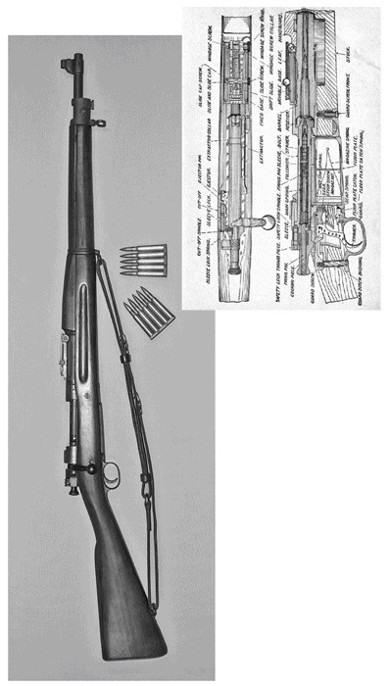

Four years after the charges at San Juan Hill, following extensive testing, experimentation, and input from veterans including Roosevelt, the Springfield Armory unveiled the five-round-magazine, stripper-clip-fed, bolt-action M1903 Springfield. Officially called the “U.S. Rifle, Caliber .30, Model of 1903,” it was known by troops as the “aught three,” or, in later years, simply “the Springfield.” There were a few key differences and improvements, most notably in the firing pin, but the aught-three was pretty much a Mauser. In fact, the Americans plagiarized so badly that the U.S. government lost a lawsuit brought by Mauser and was forced to pay the foreign company hundreds of thousands of dollars in royalties. Still, the United States had its gun.

Teddy loved the new Springfield 1903 so much he put in an order for his own custom-made hunting model. For the next twelve years he used the rifle to bag more than three hundred animals on three continents, including lions, hyenas, rhinoceros, giraffes, zebras, gazelles, warthogs, hippopotamuses, monkeys, jaguars, giant anteaters, black bears, crocodiles, and pythons.

But there was one thing Roosevelt hated about the rifle’s original design. He thought the weapon’s slim, rod-type bayonet was a piece of junk. He wanted it changed, so he halted production.

The M1903 Springfield. It so closely “borrowed” from the Mauser design that the U.S. government was forced to pay royalties to the German company.

Wikipedia

“I must say,” he fumed in a memo to Secretary of War William Howard Taft, “I think that ramrod bayonet about as poor an invention as I ever saw.” The point of the slim bayonet was to serve as an emergency ramrod in case the rifle jammed. Roosevelt as well as countless Army men realized it was too fragile to do its main job. So in 1905 a sixteen-inch knife-style blade bayonet was added. The bayonet was a real beast; the devil himself wouldn’t have wanted to pick his teeth with it.

Even better was the improved ammo, which was introduced in 1906. The new cartridge was based on the old one, but had a lighter, 150-grain pointed “boat tail” bullet at its head. It became the classic American military round for decades, and remains probably the most popular civilian hunting round today. Known as the .30-06, the “aught-six” refers to the year it was introduced rather than the size of the ammo. The new ammunition made the 1903 Springfield rifle a superstar, conferring the advantages of greater speed, force, and accuracy than a round-tipped projectile. Along with the new ammo the barrel was shortened, making it a bit easier to handle.

You may have noticed that the size of rifle bullets has started coming down. Throughout history, there was a tradeoff between speed and size, weight of the gun, and ease of use. It’s tough to make a blanket statement about what ammo or bullet is better without viewing the entire system or the job that needs to get done. The rifles the Americans had in Cuba fired bigger bullets than the Spaniards; obviously that wasn’t an advantage there. But here’s an interesting observation from that war, made by Roosevelt himself:

“The Mauser bullets themselves made a small clean hole, with the result that the wound healed in a most astonishing manner. One or two of our men who were shot in the head had the skull blown open, but elsewhere the wounds from the minute steel-coated bullet, with its very high velocity, were certainly nothing like as serious as those made by the old large-caliber, low-power rifle. If a man was shot through the heart, spine, or brain he was, of course, killed instantly; but very few of the wounded died—even under the appalling conditions which prevailed, owing to the lack of attendance and supplies in the field-hospitals with the army.”

That’s an observation that would be made again, though in different words and context, when rifle technology took another step forward (and half-step back) with the birth of the M16 family and its 5.56 × 45mm rounds.

With the new .30-06 cartridge giving the gun serious stopping power, the 1903 Springfield became one of the best infantry rifles in the world. The Germans had a decent weapon themselves in the Gewehr 98, another improved Mauser. I’ve heard it contended that the Springfield’s manufacturing was more consistent, but on the other side of that people say its firing pin is weaker than the Mauser’s.

Take your pick. I’d happily shoot either or both any day of the week.

The Springfield 1903 first saw action in the U.S. military operations in the Philippines, Nicaragua, Dominican Republic, and in General John “Black Jack” Pershing’s deep penetration raids into Mexico, in pursuit of Pancho Villa. When World War I started, it was ready for war before the Doughboys were.

On June 2, 1918, it looked like the Germans were about to win World War I.

The Russian army had collapsed and a peace treaty between the two countries was signed in February. That set nearly fifty German divisions loose. They were switched to the Western Front, and the German General Staff got ready to push the Allies to the sea. German planes bombed Paris; their long-range guns lobbed shells in the direction of the Eiffel Tower. The British high command started planning how to get its troops back to England without having them swim. The German army had seized the initiative and shattered the spirit of the Allies. Oh, and they had Mausers, too.

“A quiet moment in the German trenches.” Various Mauser rifles lay in position on top of the trench.

Library of Congress

The imminent capture of Paris was likely to deliver a psychological blow the French would never recover from. The Germans pressed on, sure that the Allies would soon be forced to sue for peace. Just forty-five miles northeast of Paris, near a patch of forest called Belleau Wood and the town of Chateau-Thierry, U.S. Marine Corps Colonel Albertus Wright Catlin saw the leading edge of the methodical German advance as it steamrollered through the French lines. “The Germans swept down an open slope in platoon waves,” he recalled, “across wide wheat-fields bright with poppies that gleamed like splashes of blood in the afternoon sun.”

It was a thing of beauty, unless you were tasked to stop it. The French troops fell back, fighting as they retreated across the wheat field. “Then the Germans, in two columns, steady as machines,” wrote Colonel Catlin. “To me as a military man it was a beautiful sight. I could not but admire the precision and steadiness of those waves of men in gray with the sun glinting on their helmets. On they came, never wavering, never faltering, apparently irresistible.”

What the Germans didn’t know was that a force of thousands of tough young U.S. Marines was lying in wait for them, supported by thousands more U.S. Army troops nearby. In a desperate, last-second move, they had been rushed to the scene as a blocking force to stop the German advance.

It had been more than a year since America declared war on Germany, but its troops had yet to play a major role in any battle. That was because the Allied high command didn’t think the American forces were ready to fight. They thought them soft and unprepared. Before they arrived in 1917, one British general even proposed that American recruits be used directly as replacements in British divisions, entirely under British command.

The Americans told them what they could do with that.

Even so, General Pershing, the commander in chief of the American Expeditionary Force, knew there was a lot of truth in the harsh assessment of his troops. He spent the better part of 1917 and the first half of 1918 training them up.

Now they were ready. Black Jack, who we saw in Cuba as a lieutenant, had been urging the reluctant allies to get his Marines and soldiers into real action for months. The German offensive made the French so desperate they had no choice. The U.S. Second Division, which included a brigade of Marines, and the Third Division were moved into positions along the line of the expected German advance.

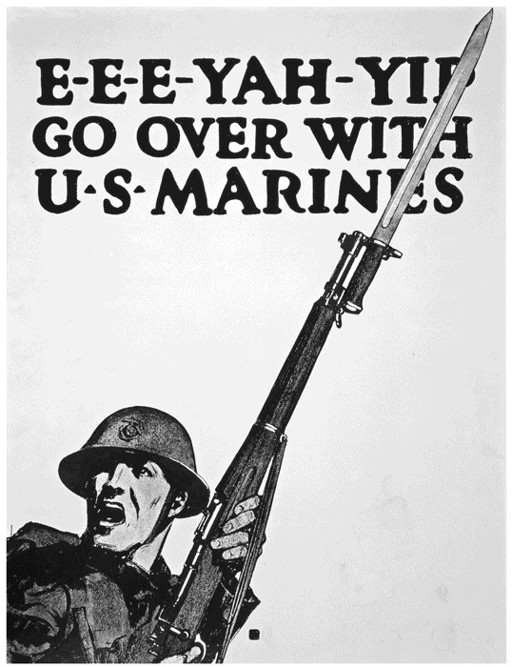

World War I recruitment poster featuring a Marine and his trusted M1903.

Library of Congress

Every one of the Marines lying in ambush was a highly skilled, long-range rifleman. The Marines were supported with some artillery and machine guns, but their main instrument of battle was the light, accurate, bayonet-tipped M1903 Springfield rifle. Each Marine had endured eight weeks of brutally intense training at Parris Island, South Carolina, drills that included extensive practice in the care and feeding of his rifle. Besides long-distance marksmanship, there was also close-quarter bayonet and hand-to-hand combat training. Unlike the Army, which assumed mass firepower from large units and didn’t pay too much attention to marksmanship, the Marines started from the idea that they’d be fighting in small units that had to make every shot count.