American Gun: A History of the U.S. In Ten Firearms (19 page)

Read American Gun: A History of the U.S. In Ten Firearms Online

Authors: Chris Kyle,William Doyle

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction

We ordered a bunch of parts and went to work. Monty started by taking a Remington 700 action and truing it. This meant going over the workings until they were to exact specifications, removing what for most people wouldn’t even be considered blemishes. He put a Rock Creek barrel on it, and then added a number of other high-tech, top-shelf parts. One of Monty’s little personal touches had to do with the way he bedded it into the Accuracy International chassis he used. There’d been the tiniest external warp to the action, and he cured any flaw that might have caused.

When he was done, the weapon was a sub-half MOA gun, or accurate to within a half-minute of angle when fired at a target at one hundred yards away. It’s a standard snipers and marksmen use to gauge a gun’s accuracy without interference from the shooter. In this case, it meant that five military spec bullets hit less than a half-inch apart when fired. Rifles have been improving steadily over the past few years, but that’s a damn good grouping by any measure.

Monty’s been building guns since he was a teenager, and taking them apart before that. He probably hasn’t met a weapon he doesn’t think he can improve on. Chief LeClair is still in the Navy, but he ought to eye a career as a gunmaker if he ever retires.

Toward the end of my service as a SEAL, we started working with guns that fired the .338 cartridge, a larger round that in the right weapon has tremendous power and range. The .338 Lapua Magnum round is a great option; in fact, it’s the ammunition I was shooting when I got my longest kill, at some 2,100 meters outside Baghdad. I was able to use both a McMillan and an Accuracy International version of the 338; I was on the McMillan when I made that shot. The bullet shoots farther and flatter than a .50 caliber, weighs less, costs less, and will do just as much damage. While the guns are heavier than those designed to fire a WinMag, they’re a good sight lighter than a .50. They’re awesome weapons.

In case you’re wondering, the round is named Lapua after the Finnish company that developed it in the 1980s. The bullet was first intended for a gun being developed by Research Armament Industries in Arkansas to meet a Marine Corps requirement for a new long-range sniper weapon to replace .50 caliber sniper guns. The gun, known as the Haskins rifle after its designer Jerry Haskins, influenced a new generation of designs.

To stand up to the round, the gun required a thick bolt and a wider frame for the action; one of the first companies to produce such a weapon was Mauser, which came out with a .338 Magnum SR93. A lot had changed in a hundred and twenty years since their rifles buzzed past TR’s ears, but the company, now a subsidiary of Sig-Sauer, still aimed for the cutting edge of gun design.

Since we’re talking about sniper weapons and the cutting edge, I should mention that some of the most important developments in the technology have come in the area of optics. There’s no sense having a gun that will shoot 2,000 meters if you can’t see what you’re aiming at. Improvements in scopes and guns are being made every day. And then there’s this: One system I looked at recently allowed the gun—or more specifically its computer—to decide when to take the shot. With that system, say its developers, anyone can be a sniper.

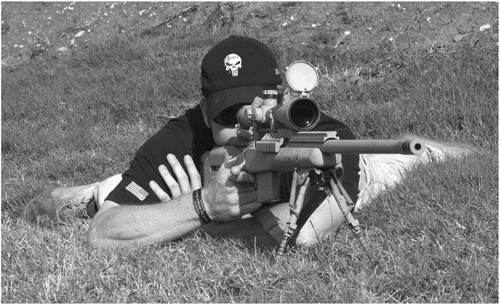

Here I am with my Lapua .338, a distant relative of the bolt-action M1903.

The Kyle family

I don’t know about that.

The sighting system sure is sweet, and the gun definitely packs a wallop. Is it the future? I guess we’ll find out.

The Springfield M1903 enjoyed a long run. It lives on today not only in the hands of collectors and shooters who like its solid feel, but in movies and classic novels. Steve McQueen handled a Springfield in

The Sand Pebbles,

and an M1903 with a telescopic sight was used by the sniper played by Barry Pepper in

Saving Private Ryan.

Ernest Hemingway and Kurt Vonnegut wrote Springfields into their stories, and in James Jones’s

From Here to Eternity,

soldiers drilled with Springfields and fire them at Japanese aircraft on December 7, 1941.

But another gun developed in the pre–World War I era had an even greater role in movies and popular culture.

I’m talking about the M1911 pistol, standard sidearm for the U.S. military from 1911 to 1985, and the gun that defined semi-automatic pistol for several generations of Americans.

“Beyond a doubt, there is no other service handgun made in the lifespan of the Colt .45 that can equal—or even approach—that of the M1911 Government Model when it comes to resolving conflicts, stopping fights, and keeping Americans alive and fighting.”

—Wiley Clapp,

American Rifleman

On October 18, 1918, a tall, red-haired American Army corporal found himself behind enemy lines in the Argonne Forest in France.

German machine gunners on a nearby ridge were sweeping the bushes around him with bullets. A slug slapped a hole in his helmet, though it somehow left his skull intact.

The corporal had two weapons: a rifle and a handgun. The first was an M1917 Enfield bolt-action rifle, a British rival to the Mauser and Springfield that was a little cheaper to make. The second was a .45-caliber, semiautomatic Colt service revolver with the official name of “Automatic Pistol, Caliber .45, Model 1911.” It was a weapon that in the right hands could turn bad luck good. It simply kicked ass.

Just like the guy holding it.

The trapped U.S. Army corporal’s name was Alvin Cullum York, and the pickle he found himself in had materialized quicker than a New York minute. Bare moments before, the soldier and sixteen other men from Company G, 328th Infantry, 82nd Division, had surprised a group of German troops and taken them prisoner behind the lines. But before they could organize the POWs, the Americans came under concentrated machine gun fire. Nine, including the sergeant leading the three squads on patrol, fell to the ground, all dead or severely wounded.

They were spotted and pinned down by a force that outnumbered them by 20 to 1. Six Americans were shot dead.

“The Germans got us, and they got us right smart,” remembered York. “They just stopped us dead in our tracks. Their machine guns were up there on the heights overlooking us and well hidden, and we couldn’t tell for certain where the terrible heavy fire was coming from. . . . And I’m telling you they were shooting straight. Our boys just went down like the long grass before the mowing machine at home.”

York grew up in the mountains near the Tennessee-Kentucky border. Before the Army, he’d been a hard drinker, a brawler, and a bit of a redneck goof-off. Somehow, he’d grown into a gentle, God-fearing Christian. He’d also become a pacifist, and tried for conscientious-objector status. In fact, it had taken a long talk with his unit commander before he decided his duty as a soldier didn’t conflict with his beliefs.

Crouched on the ground, York held his bolt-action Enfield with one hand as bullets flew over his head. He waited for the machine gunner above to stop firing and look down. York was between the prisoners and the machine-gun nest, so close to the enemy that the German had to pitch the barrel down sharply to get at him. The nearby POWs made things tougher for the gunner; he had to get a good fix on his target before firing or risk killing his own people.

Sure enough, a head popped up. York squeezed the trigger.

The German disappeared, dropped by a .30-06 round from York’s rifle. York waited. Up came another head, York fired, and the enemy vanished.

“That’s enough now!” he yelled out in his hillbilly drawl.“You boys quit and come on down!”

The Germans didn’t take his advice. They’d been in the war long enough to know that his Enfield had only five rounds in the magazine, so maybe when a lieutenant and five men jumped out to take him with bayonets, they figured they had numbers on their side.

Problem was, York didn’t use his rifle next. He switched to his M1911 pistol. And instead of taking down the first man in line, which might’ve sent the others scurrying to the ground, he worked from back to front, popping them one at a time until finally it was the lieutenant’s turn. The German officer fell with a scream, gut-shot.

“You never heard such a racket in all of your life,” said York, talking about the battle after it was done. “I didn’t have time to dodge behind a tree or dive into the brush. . . . There were over thirty of them in continuous action, and all I could do was touch the Germans off [shoot them down] just as fast as I could. I was sharp shooting. . . . All the time I kept yelling at them to come down. I didn’t want to kill any more than I had to. But it was they or I. And I was giving them the best I had.”

Finally, York sensed someone behind him. He spun around to see a German officer in the woods with an empty Luger pistol. The German had been trying to shoot him, but missed every time. Spooked and sure that York would kill every last member of his unit, the man offered a deal;

If you don’t shoot anymore, I’ll make them surrender.

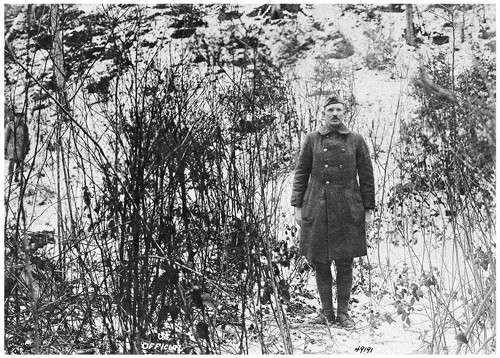

Above: Sgt. Alvin York after receiving the Medal of Honor. Below: Sgt. York in winter 1919, “standing in front of hill where 132 German prisoners were taken in Oct. 1918.”

Library of Congress

Covering the officer with his M1911, York told him to go ahead. The lieutenant blew a whistle, and fifty Germans emerged with their hands up. More followed.

One die-hard threw a grenade at York and the six other Americans who’d survived. The grenade missed. York didn’t. Another German stalled when told to leave his machine gun. York shot him, too.

“I hated to do it,” he said later. “He was probably a brave soldier boy. But I couldn’t afford to take any chance so I let him have it.”

York ordered the officer to guide them toward American lines. The mass formation marched off, with the seven Americans using the Germans as human shields. They gathered more prisoners as they went.

After they reached safety, York reported to battalion headquarters. “Well, York, I hear you captured the whole damned German army,” said his brigade commander, General Julian R. Lindsey.