American Gun: A History of the U.S. In Ten Firearms (27 page)

Read American Gun: A History of the U.S. In Ten Firearms Online

Authors: Chris Kyle,William Doyle

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction

Interviews with German prisoners revealed that many of them were spooked by the superior firepower delivered by the Americans’ M1 Garands. They were sometimes mistaken by green German infantrymen to be portable and terribly accurate high-powered machine guns.

The Battle of the Bulge, which started with a surprise attack in mid-December 1944, was Hitler’s last-ditch counteroffensive to try to stop the Allied express. The Germans massed the best of their divisions along the Western front, which roughly coincided with the German border, then tried to drive a wedge through the American line. The plan was like a Hail Mary with ten seconds to go in a football game, but given where Germany found itself, they had to take some sort of gamble or just give up.

At first, the Nazis kicked the Americans all through the Ardennes Forest. The XLVII (47th) Panzer Corps ran through the weak sector in Omar Bradley’s armies, punching so deeply into Belgium that Eisenhower thought he’d have to retreat to the other side of the Meuse. One of the reasons that didn’t happen was the arrival of the 101st Airborne at the little crossroads town of Bastogne. The paratroopers, who’d just spent several weeks slugging through Holland, were supposed to be getting a little R&R. Instead, they were packed into trucks and driven to Belgium, where they were told to hold a key crossroad in front of the German advance. They were just about surrounded on December 22 when the German corps commander, General der Panzertruppe Heinrich Freiherr von Lüttwitz, gave them an offer he didn’t think they could refuse: surrender, or we’ll bulldoze you.

Brigadier General Anthony C. McAuliffe made his answer short and sweet:

“To the German Commander,

Nuts!

—The American Commander.”

The Germans probably had a little trouble translating that until the paratroopers helped out with some precision M1 shots from their hunkered-down positions.

Bastogne was relieved on December 26 when advance units from George Patton’s army, diverted north by Bradley, punched through the German troops surrounding them. The German advance was running out of gas, but the Wehrmacht was not about to retreat without a fight. Bad weather and bad blood between the British and American commanders under Eisenhower hampered the counterstroke. When it finally got under way, it slogged slowly through frozen terrain. The Germans, their backs to their border, fought like cornered wolves.

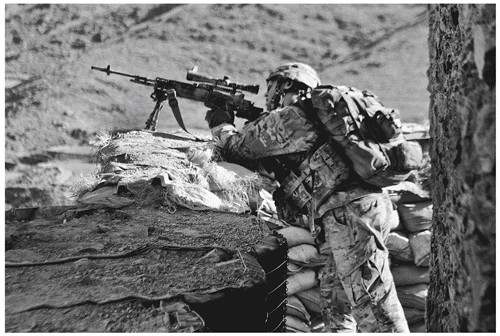

An American aims his Garand at a Nazi.

National Archives

Private Joseph M. Cicchinelli was part of A Company, 551st Parachute Infantry Battalion attached to the 82nd Airborne Division, near the Belgian village of Dairomont. Though the 82nd never got the press the 101st did, they had also rushed to the rescue at the start of the Battle of the Bulge. Holding the line on the northern side of the German advance, they had just as important a job, and took as bad a beating in some places.

As the Americans went from defense to offense, the unit joined the counterattack. Cicchinelli’s platoon was told to take Dairomont, one of a series of small towns commanding the crossroads south of Spa and Leige. The woods were filled with snow and dead soldiers on both sides. It was so cold a private was discovered frozen to death that morning. Supplies were low; some guys hadn’t eaten in two days.

The battalion commander ordered a frontal attack on the village. The Americans poured M1 and Thompson submachine gun fire at German positions, but their attack stalled. There was the danger of friendly fire as two squads encircled and rushed the enemy from two different directions in the late afternoon fog. So platoon leader Second Lieutenant Dick Durkee ordered a desperate maneuver.

“Fix bayonets!” came the command. The men pulled bayonets out and snapped them below the muzzles of their M1s.

Thirty American soldiers charged through knee-deep snow toward a German machine-gun nest. The position was guarded by foxholes. Durkee reached the first foxhole, swung his rifle around, and cracked an enemy soldier on the head with the butt end of his Garand. Then he moved on to the next. “We reached the enemy position, and leaped from foxhole to foxhole, thrusting our bayonets into the startled Germans,” Cicchinelli remembered.

In less than thirty minutes of hand-to-hand combat, sixty-four Nazis were dead.

Some Germans thrust their hands up to surrender, but “they never had a chance,” recalled Durkee. “The men, having seen so many of their buddies killed and wounded during the past twenty-four hours, were not in a forgiving mood.” By the time the fighting was over, thirty half-frozen, half-starving American GIs with bayonet-tipped M1 Garands had liberated the village of Dairomont.

Later that spring, having repelled the Nazi’s furious final counterpunch, American GIs hoisted beer mugs and bottles of wine inside the ruins of Hitler’s luxury mountain retreat at Berchtesgaden. Their M1 Garands were stacked along the wall. On May 7, 1945, two weeks after Hitler used a Walther BPK 7.65 pistol on himself, General Eisenhower accepted the German surrender.

The M1 Garand saw action again in the Korean War, where its durability meant life or death during the coldest months of the war. One Marine veteran of the fight, Theo McLemore, said later that the trick to keeping the M1 Garands working was to run the weapon dry: wipe out all traces of oil and lubricant from the rifle, which otherwise froze and jammed the gun. That is definitely not something you want to try at home, but apparently the Garands could handle it.

“Not having any oil or grease was hard on the weapons,” McLemore admitted, “but removing it allowed us to use our M1s even when the temperature got down to 40 below. The M1 was our best weapon, and we really relied on those rifles.”

The M1 served faithfully, but its time had passed. Being able to squeeze off eight shots without reloading had been a godsend in the 1940s. Now it was not enough by half. More versatile automatic and semi-automatic weapons, made possible by gas systems, were clearly the way of the future.

The problem was how to get there.

The M1 was a proven weapon system, so it was natural to try to improve it. Different trials during and right after World War II gave test versions more rounds and the ability to fire fully automatic. The truth is, none of these experiments was very successful. A much more promising rifle, known to history as the T25, was developed as an alternative. Despite its potential, the T25 didn’t get far in development. Politics took over—there’s a shock—and the eventual winner in the contest to replace the M1 was the M14, the next branch on the Garand’s evolutionary tree.

The worst thing about the M14 was that it wasn’t the AK47, which appeared in Russian hands shortly before the M14 was announced. The AK47 was a groundbreaker and an icon. It was the best gun of its day. Although it’s a far cry from my favorite, it’s still a deadly and popular weapon the world over.

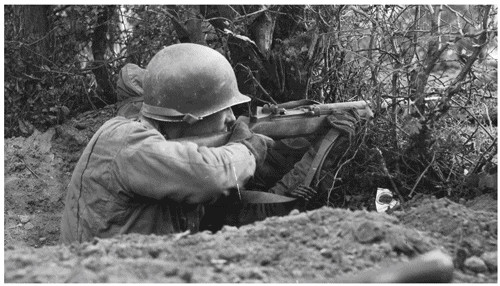

Medal of Honor recipient Baldomero Lopez leading his Marines and their M1s in Korea, 1950.

National Archives

The second worst thing about the M14 was that it tried to be all things to all people. It was specified that the gun had to meet a wide range of requirements—accuracy at distance, fully automatic fire, ruggedness, and all that. But they just didn’t work together well in that platform or with the cartridges it was designed to fire.

The M14 was adopted in 1957 and served with frontline troops early in the Vietnam conflict. There were drawbacks and complaints right off. The rifle was difficult to control on automatic fire. The weight and size of the weapon made it a bit of a pain to use if you had to hump long distances in the jungle. Soldiers said the humidity swelled the wooden stocks, eroding the gun’s accuracy.

But the gun was good at some things. For one, as long as you didn’t use it on full-auto, it was very accurate. It fired a big, man-stopping round which could penetrate the thick jungle canopy. In fact, if you thought of it simply as an M1 on steroids, an improved semi-automatic that used a twenty-round magazine instead of a clip, it wasn’t a bad gun. If you put a scope on it, or if you were truly skilled in the use of its iron sights, the M14 was a lethal and dependable infantry weapon. It wasn’t an AK, and as long as you remembered that, you were good to go.

Some soldiers kept the gun, preferring it over its replacement, the M16. But there were plenty of critics. It didn’t help that the government had spent millions in taxpayers’ money to develop it, and another $140 million to produce it. And that was back in the days when a million dollars was a

million dollars.

The editor of

Army Times

called the M14 “nothing more than the M1 Garand with a semi-automatic position and an uncontrollable fully automatic position.” A report by the comptroller of the Department of Defense put it down as “completely inferior” to the World War II–era M1 in September 1962. The worst cut of all came from John Garand himself, who claimed the gas system was “bunk. I tested it and it doesn’t work the way they claim.”

But a funny thing happened to the M14 on the way to the scrap heap. The gun’s accuracy and its ability to shoot a number of rounds without having to change the magazine suggested to some that it could be the basis of a good sniper weapon.

The M14’s sniper brother, the M21, turned out to be a very useful sniper weapon. It served from the Vietnam War into the 1980s. A new and improved version, the M25, started being used around the time of the first Gulf War.

SEALs used the M14 for different tasks, never completely letting go of the older gun and its powerful rounds. They did this despite the limitations: the weapon was designed at a time when body armor wasn’t common, and things like lasers and night scopes were still mostly things in science fiction books.

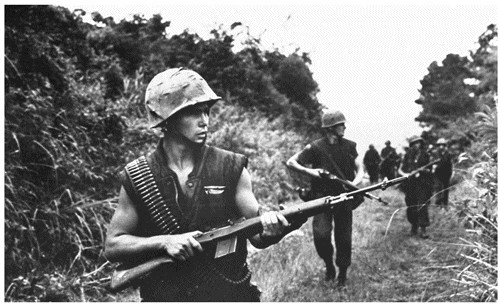

An American on patrol in Vietnam with an M14.

National Archives

Being SEALs, they couldn’t leave well enough alone—they had to make it better. A much improved version, the SEAL CQB rifle, also known as the M14 Enhanced Battle Rifle, eventually emerged as a modern variant of the original. From the outside, the weapon looks nothing like the wooden framed gun of the 1960s. It’s heavier, and there’s not a wood grain in sight. But it still has the heart of the gun that won World War II deep inside.

Craig Sawyer is a security consultant and the star of a bunch of reality shows, including

Rhino Wars

and

Top Shot.

Back in the day, he was a SEAL sniper, and among his favorite weapons was an M14. We traded notes at a recent SHOT Show, and swapped stories.

In the Teams, Craig used a customed sniper rifle that was tailored to be mission specific. Today his sponsors give him access to the best gear he can find. But he still goes old school when he can. Having learned to shoot as a kid in Texas—yup, we’re everywhere—Saw still feels comfortable doing things the old-fashioned way. No wonder: I’ve heard some incredible stories about shots he pulled off from helicopters using just an M14 with no scope.