American Legend: The Real-Life Adventures of David Crockett (30 page)

Read American Legend: The Real-Life Adventures of David Crockett Online

Authors: Buddy Levy

Tags: #Legislators - United States, #Political, #Crockett, #Frontier and Pioneer Life - Tennessee, #Military, #Legislators, #Tex.) - Siege, #Davy, #Alamo (San Antonio, #Pioneers, #Frontier and Pioneer Life, #Tex.), #Adventurers & Explorers, #United States, #Pioneers - Tennessee, #Historical, #1836, #Soldiers - United States, #General, #Tennessee, #Biography & Autobiography, #Soldiers, #Religious

That evening Crockett was treated to a banquet that included esteemed colleagues and fellow supporters of the United States Bank. Among them was Gulian Verplank, the man who had defended Crockett’s conduct, and by extension, his honor, back in 1828 when he wrote the letter assuring Crockett’s gentlemanly behavior at the Adams’s dinner. Also in attendance was Augustin Smith Clayton, the probable author (though the book was published in Crockett’s name) of the spurious

Life of Martin Van Buren, Hair-Apparent to the “Government” and the Appointed Successor of General Jackson.

28

Clayton gave a short speech, followed by Crockett, who by now must have been a bit travel weary despite the excitement of his surroundings. On May 1 Crockett visited various newspaper offices and met with their editors, then toured the noted Sixth Ward.

Though he knew that the tour was bolstering book sales, his enthusiasm for making canned speeches and serving as puppeteer for Whig party propaganda began to flag, and he balked at a well-advertised and well-attended appearance at the Bowery Theatre. After some coaxing by his hosts, Crockett agreed to a brief visit, after which he abruptly adjourned to his lodging—he may truly not have felt well.

29

A good night’s rest revived his spirits, and the next day he participated happily in a shooting match and demonstration in Jersey City, which cheered him up and perhaps reminded him why he was there in the first place—for himself, to elevate and cement his public persona. The Whigs had different ideas, of course, and perhaps through his obstinacy and behavior in the Bowery they began to see that his independence might prove too roguish to rein in. Perhaps he was not as politically or personally pliable as they had hoped. Still, the gunplay and hunting demonstration encouraged Crockett, and in the late afternoon he boarded a steamship bound for Boston, via Newport and Providence, brief stops where Crockett waved and bowed to applauding masses.

It was now time to go through a similar meet-and-greet routine in Boston. Between speaking appearances he also visited factories, including one in Roxborough, where the owner gave him a fine hunting coat manufactured on the premises. He now had a fitted rifle and a new hunting coat, and had recently been shooting, all of which would have reminded him of his home in Tennessee, where he had not set foot in many months. On May 7, Crockett visited Lowell to see the mills and was given a tour by textile tycoon Amos Lawrence, a proud and dignified captain of industry. Lawrence presented Crockett with a finely tailored domestic wool suit fabricated by Mississippi haberdasher Mark Cockral.

30

That evening, Crockett dined with “one hundred” Lowell Whigs and spoke in glowing terms of the cleanliness, quality, and beauty of the manufacturing operation and its products and materials, even “praising the health and happiness of the five thousand women toiling in the mills.”

31

This first phase of the tour was drawing to a close, but as the Whigs wished it to end on a high-profile note, they had arranged for Crockett to dine with Whig luminaries at the lovely home of Lieutenant Governor Armstrong. After dinner, Crockett was taken to a theater, for the purpose, as he put it, “to be looked at.”

32

He must have begun to feel like one of the specimens on parade at Peale’s Museum of Curiosities and Freaks, with people standing shoulder to shoulder just to get a look at him. It would have been simultaneously flattering and taxing, for Crockett truthfully did value his freedom, and he would have sensed that the Whigs were manipulating him for their own purposes. For now, he was willing to go along with the ruse, since he stood to gain from the media attention.

Crockett had been hosted in first-rate manner throughout the tour, and Whig supporters picked up every dinner tab and bar bill, even paying for his accommodations. He was likely also supplied with spending cash, “handshake money” designed to keep him flush. Despite the accolades, the frenzied book sales, and the star treatment, he would have been relieved to be making the return trip toward Washington, with just a couple of mandatory stops along the way. After declining an evening of dining and speaking in Providence, Crockett acquiesced in Camden, New Jersey, where he sermonized for “about half an hour” before a large and appreciative gathering, then boarded a boat for Philadelphia.

33

Back again in Baltimore, the tour having come full circle, Crockett met a massive and adoring horde, many of whom followed him to his lodgings at Barnum’s Hotel, where he made yet another speech and waved good-bye to his fans, relieved for this leg of the tour to have concluded. He limped back into Washington on May 13, drained from the sheer pace of the trip, and perhaps a bit self-conscious about whether or not he had compromised his own principles. Part of his speech along the way had included the conviction that he was “no man’s follower; he belonged to no party; he had no interest but the good of the country at heart; he would not stoop to fawn or flatter to gain the favor of any of the political demagogues of the present time.”

34

It would take tremendous denial not to see the irony in such claims, as it certainly appeared that David Crockett was in cahoots with the Whigs, despite claims of being a man bowing to no party. They had auditioned him to see how he might play two years later. If he proved not to be potentially “presidential,” that was okay, too. At least he had served to publicly criticize the Jackson administration at every stop. It had been a very clever scheme on the part of the Whigs, with virtually no downside.

35

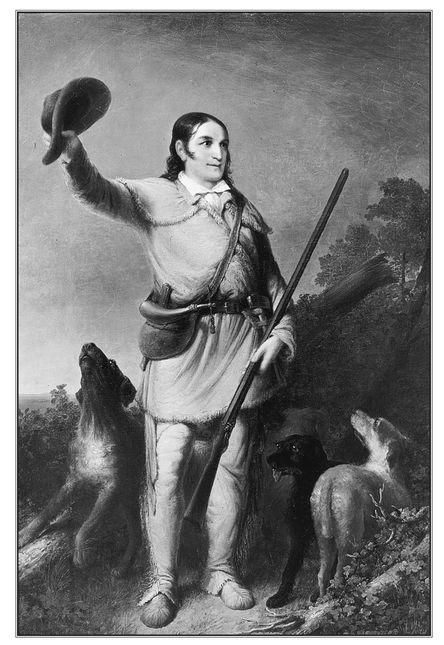

Fresh from his whirlwind tour and feeling haggard but still quite full of himself, Crockett agreed to sit for a portrait by the painter John Gadsby Chapman. Crockett had lost one portrait previously, unfortunately leaving it on a steamboat, and the others he had sat for in the past few years had failed to impress him much, or, to his mind, capture his likeness in a convincing and—perhaps more important—memorable fashion. Crockett found the previous portraits too formal, making him appear, as he put it, like a “sort of cross between a clean-shirted member of Congress and a Methodist Preacher.”

36

He decided he could help orchestrate the image, in effect becoming the costume designer and art director for the project, and Chapman gave Crockett full rein. Crockett launched enthusiastically into the work, thrilled by the collaborative possibilities: “We’ll make the picture between us,” he told Chapman, it would be “first rate.” Then epiphany hit Crockett like a flash of lightning in a hurricane—the best portrait for posterity, the one he wished to be remembered, was out hunting in a “harricane,” dressed in full leathers and regalia, with all his hunting gear, tools, long rifle, and a team of likely hounds. Such a scene would be destined to “make a picture better worth looking at.”

37

Crockett took the task of this image-making very seriously, searching out the best and most authentic props: leather leggings, a worn and faded linsey-woolsey hunting shirt, a battered powder horn, a hatchet or tomahawk, a butcher knife, and a pack of scurvy-looking dogs that appeared worn from the hunt. Finally, Crockett coordinated the pose itself, choosing one of action, the hunt about to begin: his felt hat in his right hand, the dogs dashing and yelping underfoot, one looking up expectantly for the word to go ahead, Crockett’s gun cradled confidently in the crook of his left arm.

38

It was the Crockett his adoring public wanted to see, not a stuffy, clean-shirted member of Congress, not a fancy gentleman dressed for an evening of society, but a rough-and-ready backwoodsman, the man who had years before poked his inquisitive head out of the Tennessee canebrakes “to see what discoveries I could make among the white folks.” He had discovered much, not the least of which was the uncanny ability to participate in the making of his own mythology. The image would complement his book, and the publicity from the tour, quite nicely.

Congressman David Crockett in full hunting regalia and with bear-hunting dogs, immortalized in the image he helped to create. (David Crockett. Portrait by John Gadsby Chapman, 1834. Oil on canvas. Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, Austin.)

Between sittings, Crockett went through the motions of his congressional duties with an animosity toward Jackson that was reaching maniacal proportions and a bilious disdain for the entire governmental process. His verbal assaults now breached all sense of decorum, and on more than one occasion the Speaker of the House was forced to call the fuming Crockett to order.

39

To make matters worse, the land bill, on which Crockett had hung practically his entire political reputation and life, was dead in the water. As the session drew near a close, on June 9 he scribbled an angry and disillusioned letter to William Hack, revealing that what little hope he had possessed now flagged. “We will adjourn on the 30 of June So I fear I will have a Bad Chance to get up my land Bill I have Been trying for some time and if I Could get it up I have no doubt of its passage.”

40

He was right about that.

He would be thwarted for the remainder of his term, until he remained nothing but a raging cipher in Congress. In late June he erupted, calling Jackson’s advisors

a set of imps of famine, that are as hungry as the flies that we have read of in Aesop’s Fables, that came after the fox and sucked his blood . . . Let us all go home, and let the people live one year on glory, and it will bring them to their senses . . . Sir, the people will let him know that he is not the government. I hope to live to see better times.

41

He had unraveled completely. Seeing him leaving the Capitol for home one day, Chapman, who had been painting him for weeks, remarked that he appeared “very much fagged” (exhausted).

42

Adding salt to his wounds were the growing criticisms of his absence from Congress for those weeks during the tour, which he attempted to salve by claiming chest pains. “I had been for some time,” he wrote in a lame defense, “labouring under a Complaint with a pain in my breast and I Concluded to take a travel a Couple of weeks for my health.”

43

But no one was fooled, as his movements and appearances across the eastern seaboard had been widely published in the

Niles Register

and in many other papers across the country. His constituency began demanding answers, and without the passage of his vaunted land bill, he had nothing but excuses to offer them.

Flabbergasted and clearly at his wits’ end, Crockett exclaimed, “I now look forward toward our adjournment with as much interest as ever did a poor convict in the penitentiary to see his last day come.”

44

So anxious to escape his prison without bars was Crockett, he bolted even before the official adjournment of the session, determining to head back to Philadelphia to visit Carey & Hart, hawk a few more books along the way, pick up the rifle he had been fitted for, and surround himself once again in a cocoon of adulation, where his popularity knew no bounds.

THIRTEEN

“That

Fickle, Flirting

Goddess” Fame

R

IDING THE STAGECOACH from Washington to Baltimore, bound for Philadelphia once more, David Crockett had a lot on his mind. He was anxious, even thrilled, for the forthcoming festivities, which included hobnobbing with statesmen like Daniel Webster, with whom he would share the stage in a few days at a scheduled Independence Day fête for political speeches. As the coach jounced along and he looked out the window, he surely thought of home, his friends and family in Weakley County, which now seemed worlds away. And he would have been ambivalent about his return there. His relationship with Elizabeth had all but disintegrated, and while they remained civil, he rarely communicated with her directly. Now that he had been gone from home nearly a year, she qualified as estranged. Even worse, his eldest son John Wesley, who made him proud by following in his political footsteps, had recently given him pause. John Wesley had written to say that he’d undergone a full-fledged religious conversion. Perhaps remembering his own short-lived foray into sobriety and righteousness, Crockett scoffed at the news. “Thinks he’s off to Paradise on a streak of lightning,” he mumbled. “Pitches into me, pretty considerable.”

1