American Legend: The Real-Life Adventures of David Crockett (33 page)

Read American Legend: The Real-Life Adventures of David Crockett Online

Authors: Buddy Levy

Tags: #Legislators - United States, #Political, #Crockett, #Frontier and Pioneer Life - Tennessee, #Military, #Legislators, #Tex.) - Siege, #Davy, #Alamo (San Antonio, #Pioneers, #Frontier and Pioneer Life, #Tex.), #Adventurers & Explorers, #United States, #Pioneers - Tennessee, #Historical, #1836, #Soldiers - United States, #General, #Tennessee, #Biography & Autobiography, #Soldiers, #Religious

The ploy allowed Crockett to remain optimistic, even overconfident. With little more than a month to go in the election, Crockett exclaimed of his opponent: “I have him bad plagued for he don’t know as much as me about the Government,”

43

adding that he felt confident he would glean twice as many votes as his competitor. Crockett politicked in a frenzied fashion, accepting offers to every stomp-down, dinner, or reaping in the region, maintaining his infectious grin and patented jargon everywhere he went. Near election day he harkened back to an early threat, stating unequivocally “If I don’t beat my competitor I will go to Texes.”

44

Crockett promised to write his publishers and his Whig supporters as soon as the results of the August 6 elections were known, and he honored his claim with a long and telling letter on August 11, by which time the final tally was in. The race was tight, with Crockett picking up 4,400 votes to Huntsman’s 4,652. Sour, even bitter, and suspicious that the voting had been rigged, Crockett accused bank managers of offering a healthy $25 per Huntsman vote (a rumor Crockett had heard going round). “I have no doubt that I was Completely Raskeled out of my Election,” he wrote, adding, as was his style, a high-minded commentary on justice and righteousness, which he may well have believed: “I will be rewarded for letting my tongue Speake what my hart thinks . . . I have Suffered my Self to be politically Sacrafised to Save my Country from ruin and disgrace and if I am never again elected I will have the gratification to know that I have done my duty.”

45

The loss burned into Crockett like a brand searing a cow’s flank, and, a sore loser in the best of times and now smarting from an election he considered fixed, he was nearly out of options. Washington no longer wanted him, and now it seemed, shifty vote or no, neither did West Tennessee. His familial relations were civil, but he no longer shared a bed with Elizabeth, and to add biting insult to the painful injury of election loss, her relatives accused him of misconduct in the administration of her father’s will, which hurt his feelings deeply and festered into a familial falling-out, though nothing came of legal consequences. Still, he likely felt doubly rejected by both friends and family.

46

Then the arrogant and boasting press began to flow in from the side of the victors, proving more than Crockett could stomach. A wealthy businessman and ardent Jackson man wrote giddily to Polk, exclaiming, “We have killd blacguard Crockett at last.”

47

A local building contractor exclaimed joyously, “It gives me great pleasure to say . . . that the great Hunter one Davy has been beaten by a Hunstman.”

48

The

Charleston Courier

appeared giddy with elation, printing on August 31:

Col. Davy Crockett,

hitherto regarded as the

Nimerod of the West,

has been beaten for Congress by a

Mr. Huntsman.

The Colonel has lately suffered himself to be made a lion, or some other wild beast,

tamed,

if not caged, for public shew—and it is no wonder that he should have yielded to the prowess of a Huntsman,

when again let loose in his native wilds.

We fear that ‘Go ahead’ will no longer be either the Colonel’s motto or destiny.

49

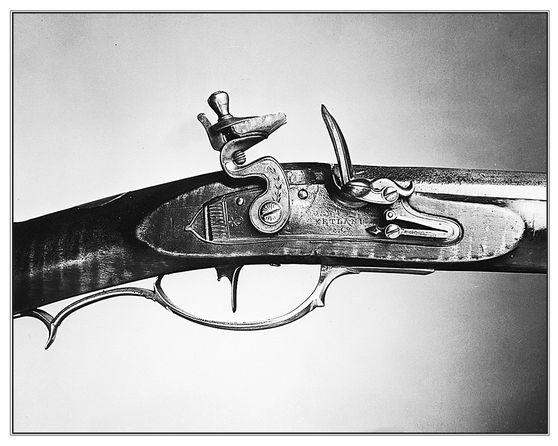

Rifle found after the battle, the kind many of the defenders, including Crockett, used during the entire siege and battle of the Alamo. (Dickert rifle, detail photograph. Daughters of the Republic of Texas Library, San Antonio.)

The Arkansas

Gazette

jumped aboard as well, hitting the man while he was down and referring to him as “the buffoon, Davy Crockett.”

It was time to cut and run. At forty-nine years of age, Crockett still had some living to do. Perhaps he recalled the conversation with Sam Houston and felt the pull of Texas. But for now, Tennessee was spent, and there wasn’t much to keep him there. He remained a celebrity in the East, but playing the role of the backwoodsman had worn thin. Perhaps it was time to actually

be

a backwoodsman again, to mount a horse, cradle a long rifle in his arms, and trot into a stiffening breeze. He knew that bison still roamed the plains of Texas, and fellows with enough grit and determination could make a go of it on the new frontier. He’d heard stories of how it was bigger than anything you’d ever imagined, plains rolling on and on into the sunset and beyond, the dirt blood-red as the sky. Maybe now might be the right time to see for himself.

He was a man of principle and a man of his word. He had said what he would do if he lost, and now he held himself accountable. He had done everything in his power to win the election, but he’d been rejected for another. Well then, that was that. They could all go to hell, and he would go to Texas.

FOURTEEN

Lone Star on the Horizon

T

HOUGH IT WAS NOT THE FIRST TIME David Crockett had lost an election, he took this rejection harder than ever, no doubt because in a very real way his defeat by Huntsman was also a victory for Jackson. Any presidential dreams or aspirations Crockett may have still harbored for 1836 were now dashed, so it was time to look to the future, quite literally toward that flaming western horizon that always tugged at him. Crockett knew, as did most people in his region and certainly everyone involved at high levels of United States government, about the growing skirmish in Texas, which even now was escalating from rebellion to revolution among the colonists, yet his attentions and motivations appeared personal at the moment. He needed, as later Westerners would put it, to “get out of Dodge.”

But he was headed toward a turbulent place. The political situation in Texas was complicated, the dominion and “ownership” of the nebulous region controversial. Spanish conquistadores arrived on the shores as early as 1519, seeking the storied “cities of gold.” Spain continued to attempt to colonize the region by setting up missions in the western and southern boundaries, maintaining this system through the eighteenth and into the early nineteenth century. But the governing seat of Spain was too far away to effectively maintain order, and more important, control a vital and growing population. Texas was simply too big a holding to manage. In the meantime, there were other claims to the territory, from both within and without. Andrew Jackson himself believed that Texas belonged to the United States as part of the Louisiana Purchase,

1

though in 1825 Jackson offered to purchase the entire territory from Mexico for 5 million dollars, but was refused.

By 1821, Moses Austin and his son, Stephen F. Austin, had negotiated a deal with Spain to set up the first authorized Anglo colony in Texas, and a clause allowed a grant to bring in 300 families to settle on the Colorado River within two miles of the ocean.

2

Later that same year, Mexico declared independence and Stephen F. Austin took on the mantle of colonization alone. His father Moses fell ill, most likely to pneumonia, and his dying wish was that his son would continue their colonization plan.

3

By 1824, Austin was able to lure prospective colonists with sweet land enticements—granting up to a full league (4,428.4 acres) of land to those willing to convert to Catholicism and sign an oath of allegiance.

4

Free land, or virtually free land was sufficient temptation, and settlers began to pour across the Red and Sabine Rivers—eventually by the thousands—carrying what little money they might have, hope for a better life, and not a lot else.

Wide-ranging and mobile bands of Apaches, Kiowas, and Comanches often attacked settlers in night raids, “sweeping down from their camps west of the Balcones Escarpment, . . . stealing horses, burning ranches, killing men, and carrying off terrified women and children.”

5

Texas remained a dangerous and inhospitable land that would need better incentives to entice the right kind of men to settle there, those willing to risk their own lives as well as the lives of their families. The land itself would ultimately prove that lure.

Initally resident Mexican settlers known as Tejanos were content with the influx of Anglo settlers, as it buffered them against the hostile Indians and provided potential for commerce and trade.

6

Over time laws were enacted to restrict further immigration from the United States, but many downtrodden U.S. settlers ignored the laws and bolted for Texas anyway, creating tension among the Tejanos and drawing the ire of President-General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna. As early as 1830, Santa Anna ordered the expulsion of all illegal settlers, “and all Texians (as they now preferred to call themselves) disarmed.”

7

The power-hungry Santa Anna went so far as to dismantle the constitutional government and Federal Constitution of 1824, effectively taking over as dictator of Mexico. Austin, watching his dream of settlement begin to disintegrate, struck out for Mexico City to lobby for Texas statehood.

8

Austin was imprisoned shortly after his arrival in early January 1834, and would have to work toward an independent Texas state from the confines of the very same prison cell once used during the Mexican Inquisition.

9

Such was the maelstrom into which Crockett had determined to ride.

NOT ONE TO SLINK AWAY from a defeat in silence, Crockett planned to depart with flying colors, making a feast of the occasion and throwing a “going-away” barbecue for himself and the others who had agreed to join him.

10

Family and friends convened at his farm in Gibson County, the late October air sweet and cool, the scent of adventure and opportunity on the wind. Crockett dug barbecue pits, and hired men tended the spitted meats while “the boys” were competing at logrolling and other games of strength and agility, and, of course, draining horns of whiskey. As the day wore on it turned into a full-fledged frolic, with dancing, more drinking, and fiddle-playing on into the evening, even through a pouring rain.

11

They reveled late into the night, with Crockett talking up Texas, convinced it was the right place to go. He could scout the land and report back to his family, and if he liked it there as much as he hoped to, perhaps he could convince them, including Elizabeth and her family, to follow him west once more. It was certainly worth a shot, perhaps the last such shot he would ever have.

On the first of November Crockett loaded the horses, packing as he would for an extended autumn-long hunt. It promised to be an expedition, like many of his scouting forays in the past, riding out to new and unknown country, the familiar thud of hoofbeats on the roadway, the acrid scent of horse sweat in his nose, saddle leather squeaking as they trotted along. He’d salted down as much meat as he could carry in saddlebags and packed plenty of powder and ammunition for the hunting, no doubt including as many canisters of the fine Du Pont powder. He must have been happier than he had been in years, finally about to embark on what he loved more than anything else in the world—a journey into a new frontier, with a few friends and his trusty hunting rifle Betsey.

12

He could hardly contain his anticipation of the journey ahead, writing with optimism to his brother-in-law George Patton, “I am on the eve of Starting to the Texes . . . we will go through Arkinsaw and I want to explore the Texes well before I return.”

13

It promised to be a trip of a lifetime, and Crockett had no set schedule for his return; it all depended on what he found when he got there.

Crockett would not be traveling alone, a fact that would have pleased the stoic Elizabeth, for she and David remained amicable if separated. Accompanying him for the long ride to the Southwest would be his nephew, William Patton, with whom Crockett got on well. Also saddled up were two friends, Abner Burgin and Lindsey Tinkle.

14

A small party was better than going solo, especially once they shook free of civilization and headed into open range and Indian country. On the morning of November 1, 1835, the four men swung onto their mounts, heeled their spurs into the flanks of their horses, and waved good-bye to their families and friends.