American Legend: The Real-Life Adventures of David Crockett (36 page)

Read American Legend: The Real-Life Adventures of David Crockett Online

Authors: Buddy Levy

Tags: #Legislators - United States, #Political, #Crockett, #Frontier and Pioneer Life - Tennessee, #Military, #Legislators, #Tex.) - Siege, #Davy, #Alamo (San Antonio, #Pioneers, #Frontier and Pioneer Life, #Tex.), #Adventurers & Explorers, #United States, #Pioneers - Tennessee, #Historical, #1836, #Soldiers - United States, #General, #Tennessee, #Biography & Autobiography, #Soldiers, #Religious

My Dear Sone and daughter

This is the first I have had an opportunity to write you with convenience. I am now blessed with excellent health and am in high spirits, although I have had many difficulties to encounter. I have got through safe and have been received by everyone with open cerimony of friendship. I am hailed with hearty welcome to this country . . . I must say what I have seen of Texas it is the garden spot of the world. The best land and best prospects for health I ever saw ... There is a world of country here to settle ...

53

Crockett appears not to have finished the letter in San Augustine,

54

but instead packed it away in his satchel and ridden back to Nacogdoches, where he honored his acceptance to appear at a dinner celebration and party with the town’s prominent women and other notable citizens. That out of the way, flush with his rekindled fame and notoriety, he made his way to the office of Judge John Forbes at the Old Stone Fort on January 12. There Crockett and those who had ridden with him read over the “oath of allegiance to the provisional government of Texas,” which they had come to sign. Doing so would allow them to vote, and be voted for, in the coming constitutional convention, but also, of course, required that they fight for Texian liberty, apparently a price Crockett was more than willing to pay given the potential upside of land, leadership, military fame, and high governmental station. He would be a fool not to sign up.

But before he did, Crockett took his time, reading over the document carefully. It began, “I do solemnly swear that I will bear true allegiance to the provisional government of Texas, or any future government that may be hereafter declared.” Crockett stopped right there, read it over again, and looked up at Forbes. This would simply not do, as he was unwilling to support “any future government.” That could easily include a dictatorship, and as he ’d shown before, he refused to be yoked to any individual man. In a defiant move, no doubt accompanied by murmurs and chatter in line behind him, Crockett refused to sign unless Forbes agreed to insert the word “republican” just ahead of “government.” Impressed at Crockett ’s intense scrutiny, Forbes willingly consented, and with a stroke of the quill Crockett had signed on as a volunteer, come what may. More than twenty years since he had last carried a firearm against an enemy, Crockett had once again joined the army. His future was now.

55

They would be riding out in just a few days, and Crockett revisited the letter that he had begun in San Augustine. His tone remained confident, reflecting his thrill at the coming adventure and the incredible promise that his future in Texas held. He told them of his taking the oath, and said that “We will set out for the Rio Grande in a few days with the volunteers from the United States,” and then he pointed to his newfound political chance: “I have but little doubt of being elected a member to form a constitution for this province. I am rejoiced at my fate. I had rather be in my present situation than to be elected to a seat in Congress for life.” That last comment illustrated how his short-term memory operated, for not long before he had claimed he was completely finished with politics of any kind. He had not anticipated the reception he would receive in Texas, and Crockett was ever an opportunist. He added the firm indication that he fully intended to prosper, then bring his family to Texas to share the wealth of his bounty: “I am in hopes of making a fortune yet for myself and my family,” he wrote proudly, “bad as my prospect has been.”

56

David Crockett stood on the cusp of fulfilling his dreams, for himself, for his family, and perhaps most important of all, for his ego. He would show those doubters back in Tennessee what he was really made of, winning the wealth he had always craved, winning his family back, and in the offing, reclaiming his own identity, so long subsumed by everyone else ’s desires about who he should be.

FIFTEEN

“ Victory or Death”

I

T WAS TIME TO RIDE, to muster and mount and begin the long march—some 300 miles—toward the Rio Grande. For the last few days, ever since signing the oath that made him a soldier once again, Crockett had seen others follow suit, some inflamed by the call to arms, some, as he was, lured by the land and the freedom it symbolized. The land that stretched out before them appeared vast, subtly undulating grass prairie ground, so limitless that Sam Houston had written of it three years before, commenting in a letter to Andrew Jackson, “I have traveled five-hundred miles across Texas, and there can be little doubt but the country east of the Grand River . . . would sustain a population of ten millions of souls.”

1

Now a steady stream of those souls poured through Nacogdoches, and the steadfast and the hearty took the pledge and armed for inevitable battle.

Officially, David Crockett held no military rank, but that did not keep the small band of volunteers who began to huddle around him from appropriating him as their de facto leader. Abner Burgin and Lindsey Tinkle, with him at the start, appear to have begged off and headed home back to Tennessee, but flanking Crockett were his loyal nephew William Patton, his cousin John Harris, his buddy Ben McCulloch, and other men including Daniel Cloud, Jesse Benton, and Peter Harper. Perhaps to honor their adopted leader, they nicknamed themselves the Tennessee Mounted Volunteers.

2

There was much to do, and Crockett took charge, drawing on his expertise, still there after lying dormant for twenty-odd years, in planning to lead a small band of scouts into hostile and foreign wilderness. He procured a canvas tent to shelter his men from the biting winds and rain they might encounter, though he personally preferred to sleep under the stars whenever possible.

3

Broke as usual, perhaps as the result of buying extra rifles for the Choctaw Bayou hunt,

4

Crockett struck a deal with the government to purchase for $240 two of his long guns, some of his on-hand equipage, and the chestnut he rode, though only a very small percentage of the money was given him in cash—the remainder due him scribbled on a promissory voucher.

5

He organized what further provisions he could, and by January 16 the mustered Tennessee Mounted Volunteers were ready to ride.

Perhaps sensing that it would be his last chance for a good long time, before Crockett left Nacogdoches he had stolen some private time to finish his letter to his daughter, his prose imbued with tenderness and hope, and yet his final words reflect his understanding that there might be cause for his relatives to be concerned about him. He tried to assure them that everything would be fine: “I hope you will do the best you can and I will do the same. Do not be uneasy about me. I am among friends. I will close with great respects. Your affectionate father. Farwell”

6

And with that he slid his boot into the stirrup, slung his forty-nine-year-old frame once more into the saddle, reined his horse tight and clucked the tall steed forward. True to his own motto, he was going ahead, this time to the Texian revolution, riding headlong toward destiny.

CROCKETT AND HIS COMPANY rode La Bahia Road unhurriedly, south toward Washington-on-the-Brazos, stopping to hunt when game flushed from cover or broke from the timber, which now grew sparser and diminished behind them. Some of the men decided to detour and go gander at the rumbling Falls of the Brazos, rumored to be magnificent.

7

Crockett kept on, agreeing to rendezvous with the other boys in Washington, and the marshy terrain they soon encountered would have reminded him of the bogs and swamps he had scouted in Florida. The horses lurched and squelched through miles of mucky pools, the sulfurous stench rising like steam around them, until they finally broke onto the banks of the Rio de Brazos de Dios, the far-reaching River of the Arms of God.

8

When Crockett and the four men still with him crossed the muddy Brazos and rode into town, they found a frontier outpost literally hatcheted from river woods, immense stands of towering oaks and hickories; the newly hewn town of some 100 residents still riddled with the stumps of recent cuttings.

9

Crockett may well have expected to find Houston there, but their paths failed to cross, as Houston was off negotiating a deal with the Comanche not to interfere with the colonists,

10

and he would not arrive in Washington until March 2.

11

They had taken their time getting here, meandering as did the riverbanks they rode. He would hole up in Washington for a couple of days to rest and see what he could learn about the military situation, and find out where he might be needed.

What he learned upon arrival, and what Houston had recently discovered as well, was that the situation in San Antonio de Béxar had become grave. Colonel James C. Neill, who had been left with just a hundred or so men to guard San Antonio, which they had secured in a brief skirmish December 5, scratched out an urgent message to Houston on January 14. He explained that the conditions at the garrison were worsening, and he had received reports that Santa Anna moved north toward the Rio Grande with a large army, and that he could be attacked in as few as eight days.

12

Given the news, Houston had quickly dispatched James Bowie and a modest company of men to Béxar to shore up Neill if he could. Houston also made it clear that he wanted “the old Mexican fortifications in the town demolished so they would be of no use to the enemy,”

13

and that in-cluded the Alamo, an old Spanish mission being used as a fort, if necessary. But when Bowie reached Béxar, he found that Neill had done a superb job fortifying the garrison, buttressing the walls of the Alamo, strengthening the gun emplacements, so that upon reviewing the compound with Neill, the two men decided that in fact Béxar could be held, especially with the cannons seized in December.

14

With an injection of fresh volunteer troops, they reckoned, San Antonio could be defended for a time, anyway.

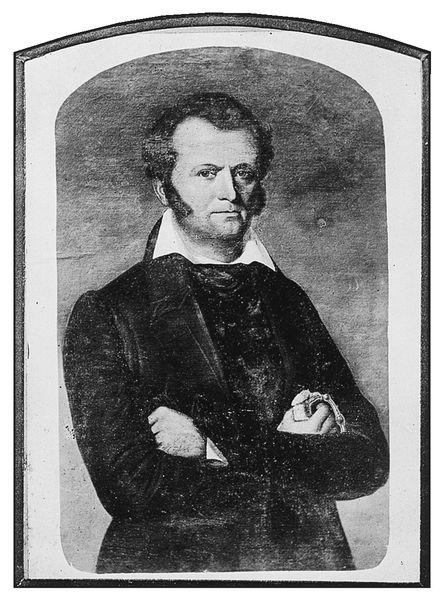

Notorious James Bowie of Louisiana led the volunteers at the Alamo until illness confined him to his quarters. (Portrait of James Bowie from glass plate negative. Lucy Leigh Bowie papers, Daughters of the Republic of Texas Library, San Antonio.)

Crockett was not the kind of man to panic or shirk danger, though upon hearing about the likely convergence of Mexican forces from the north, and Houston’s recently dispatched units heading south, his dander would have been up. He did not rush from Washington, and perhaps awaited specific orders with his small company, including John Harris, his cousin, and fellows Daniel Cloud, B. Archer Thomas, and Micajah Autry, the rest having not arrived from their split as yet.

Crockett rode out to Gay Hill, not far from town, on the afternoon of January 24, and on reaching the homestead of James Swisher he saw a man on horseback arriving with a deer slung behind his saddle, a familiar and intriguing sight for Crockett. It was Swisher’s son, John, then just seventeen but already quite skilled with his rifle. Crockett assisted the youngster in heaving the deer from the horse, complimenting the boy on his handsome trophy and asking to know the details of the shot and kill, the sorts of woodsy stories which always interested him. Impressed with the young man, who perhaps reminded him of his own boyhood, Crockett began calling John Swisher his “young hunter,” and in fun, he even challenged the lad to a shooting contest.

15

The young man was so taken by the attentions that he claimed he “would not have changed places with the president himself.”

16

Crockett spent a few days there, and his hosts recalled that during that time they never let him get to bed before midnight or one in the morning, so enthralled were they with his stories and his manner. “He conversed about himself in the most unaffected manner without the slightest attempt to display any genius or even smartness,” John recalled fondly, adding, “He told us a great many anecdotes, many of which were common place and amounted to nothing within themselves, but his inimitable way of telling them would convulse one with laughter.”

17

The Swisher family was quite honored to have the distinguished man in their midst, if only for a short time: “Although his early education had been neglected, he had acquired such a polish from his contact with good society, that few men could eclipse him in conversation.”

18

As he did with nearly every person he ever met, David Crockett left an indelible impression on the Swishers before it was time to saddle up and ride again.