American Legend: The Real-Life Adventures of David Crockett (40 page)

Read American Legend: The Real-Life Adventures of David Crockett Online

Authors: Buddy Levy

Tags: #Legislators - United States, #Political, #Crockett, #Frontier and Pioneer Life - Tennessee, #Military, #Legislators, #Tex.) - Siege, #Davy, #Alamo (San Antonio, #Pioneers, #Frontier and Pioneer Life, #Tex.), #Adventurers & Explorers, #United States, #Pioneers - Tennessee, #Historical, #1836, #Soldiers - United States, #General, #Tennessee, #Biography & Autobiography, #Soldiers, #Religious

The next morning, Santa Anna began bombarding the fort and he kept the pressure on throughout the day, pointing the bulk of his efforts on the north wall. Dismally low on powder, Travis could do no more than shrug and hold off with any retaliation, which would be token at best. He would need all ammunition and powder for the major assault, which he must have sensed looming. The only shots Travis is said to have fired that day or the next were three signal shots, aimed at any aid en route, denoting that he was still holding down the fort.

24

A few days earlier, Bowie had felt good enough to be lifted on his cot and brought out into the open air of the courtyard, and had even encouraged some of the men to stand strong and proud. But by now he was back in his quarters, his ailments gripping him to the core, clutching him in feverish shakes.

David Crockett may have been thinking of the hunting grounds he had discovered on the Red River, or favorite old haunts back home, as he looked out at the overwhelming odds they were about to face. He had done what he could to shore up the morale of the men, playing music, telling jokes and tall tales, but even his optimism would have been tested by the spectacle of being surrounded by thousands of men, the constant strain of watching the horizon and hoping for recruits to arrive. Crockett wished to be out on the open plain again, and a claustrophobic feeling overtook him as he pondered the walls of the fort now penning them in like cattle herded to slaughter. “I think we had better march out and die in the open air,” he said aloud. “I don’t like to be hemmed up.”

25

But it was only the wishful thinking of a man who longed for the freedom of open country once more, who dreamed of outriding, perhaps conjuring that idyllic Honey Grove, the twice-yearly passing of buffalo, the sweet smell of blossoms and hives dripping with honey.

Santa Anna convened a war council on the eve of March 4. A few of his officers suggested that, if the general were willing to wait for even more artillery to arrive, then the Alamo could be taken with very little loss of Mexican troops.

26

But the tactical Santa Anna craved drama, and more than that, he wished to send a message to both the rebellious “pirates” and his own troops. Attacking now, in great force, “would infuse our soldiers with that enthusiasm of the first triumph that would make them superior in the future to those of the enemy.”

27

He had already said that the attack would serve as a necessary example to Béxar and all of Texas, of the price of rebellion, “in order that those adventurers may be duly warned, and the nation be delivered . . .”

28

His mind was made up, and when the topic of how to treat prisoners of war was broached, Santa Anna scoffed and waved his officers away. His army would take no prisoners.

29

On March 5, the observant hunter Crockett would have noticed that the Mexican camp, its troops and guns, was eerily silent, the menacing electric tension of a calm before a storm. The crumbling fortress had endured twelve consecutive days of near-constant shelling, and Crockett and the rest of the men would have welcomed the respite, a chance for the ringing in their ears to cease. The quiet would give them a chance to think about their families, their goals and dreams for the future, the many trails that had led them here, and, for those who believed, what the afterlife might bring. And the tranquil air would give some of them a chance to sleep, especially those who had been trading watch for nearly two weeks, their eyes burning with sleep deprivation. Travis would send out one last messenger, a youngster named James Allen, with a last-ditch appeal to Fannin to come fast.

30

Travis then made the rounds of the garrison, posting sentries outside the walls and on guard, and then ascertaining that all the men on watch had multiple “loaded rifles, muskets or pistols,” at their immediate reach.

31

Finally, convinced he had done all he could up to now and certainly for today, Travis slumped into bed sometime after midnight.

About the time Travis was being overtaken by exhaustion, Santa Anna and his officers began rousting his men with severe whispers, poking them with staffs or kicking them awake with boots, fingers pressed to their lips, ordering complete silence for the dawn attack.

32

Crowbars and ladders were distributed, and officers made certain that all men in the attack wore shoes or sandals for ascending the walls, to assure they did not give away their positions by yelping out in agony as their bare feet met sharp rocks and thorns or prickly cactus.

33

On his command, which would be given at 5 a.m. March 6, the men were to assault in linear formation, and those in the first waves would have known they would be cut to pieces by musket fire and cannonballs tearing dreadfully at the columns of men.

34

Resolute and following orders of their supreme commander, the men shook from sleep and formed lengthy columns, their sharpened bayonets gleaming in the moonlight. Simultaneously, Sesma saddled his cavalry, their job to survey the perimeter of the Alamo and make certain that no one escaped the attack once it was under way. Though the temperatures had warmed slightly the day before, it was still cold, and the horses and men huffed cottony plumes of breath that mingled with the shimmering moonglow. The men stood shivering, holding weapons or tools, their long moon shadows ghoulish, waiting for the command to move. By 3 a.m. they stood like zombies, waiting for orders in the snap-still air. At 5:30, Santa Anna ordered Jose Maria Gonzalez to sound the call to arms, a sound inspiring the men to “scorn life and welcome death.” Other trumpeters picked up “that terrible bugle call of death,” and the columns began the assault.

35

Travis’s sentries, exhausted from weeks at their posts, stood or sat dozing, leaning uncomfortably against walls or their muskets. None detected Santa Anna’s stealthy death march, the sound of hundreds of horse hooves, or their whinnies and exhalations, the metronomic clank of metal and arms, the panicked voices of frightened foot soldiers reciting their last prayers, until it was too late. Long skeins of light tore across the embattled sky as night fought to become day, the weird moonlight lingering on the plain, bathing the fort in a surreal glow. Santa Anna’s men were upon the Alamo.

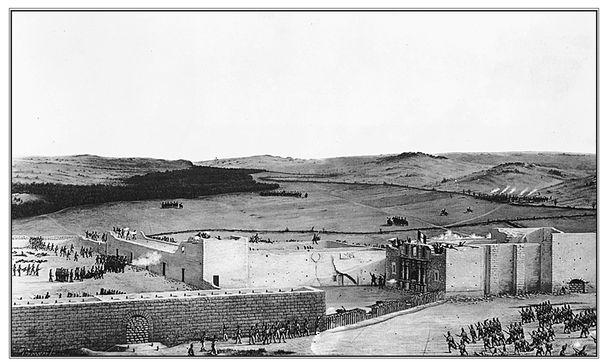

March 6, 1836, Santa Anna’s army storms the Alamo. (

FALL OF THE ALAMO

. Theodore Gentilz. Gentilz-Fretelliere Family Papers, Daughters of the Republic of Texas Library, San Antonio.)

The attackers responded to the bugles and surged forward, shouting “Viva Santa Anna” and “Viva Mexico,” and then, spurred by blood lust and their own code of honor, they also began to chant

“Muerte

[death]

a los Americanos!!”

36

Officer John J. Baugh finally woke to the commotion and sprinted to Travis’s quarters, hollering “The Mexicans are coming!” Travis instinctively clutched saber and shotgun and dashed for the north wall, his slave Joe at his heels as he reached the gun emplacement amid the horrible and confused flashes of enemy gunfire from without and the lowing and baying of terrified horses and cattle from within.

37

Inside, the Alamo awakened to the nightmare; half-dressed men streaked from their cots in the long barracks and scrambled to positions, shooting rifles randomly, igniting cannons and aiming them vaguely at the gray-black lines of men they could make out in the half-dark. The blazing, orange-yellow arcs of cannons whistled and spit skyward, then died out in the distance as the ordnances fell to the ground. Travis climbed quickly to the emplacement and looked down, seeing soldiers leaning ladders against the walls. He turned back to his men in the fort and shouted,

“Come on, Boys, the Mexicans are upon us and we’ll give them Hell!”

For a few minutes, they did. Without proper canister shot, Travis had made do, ordering the men to stuff their shotguns with “chopped up horseshoes, links of chain, nails, bits of door hinges—every piece of jagged scrap metal they could scavenge,” firing these deadly shotgun blasts on the huddled masses of men below.

38

A violent hail of fiery shards sliced down on the columnar waves of charging Mexicans, cutting many to pieces in their tracks. Travis peered over the wall at the surging onslaught, shouting encouragement and ordering another volley of shotgun blasts and a first surge of round shot in the form of nine-pound iron, when his head snapped back, a leaden ball from a Mexican Brown Bess striking him in the forehead and hurling him backward into a motionless heap against one of his own cannons, his gun still clasped in his hands.

39

Crockett was somewhere in the frenzied rush to defend, amidst the cacophony of cries from comrades taking lead balls from volleys thrown by the onrushing waves of the enemy. The inside of the fort flickered, illuminated by gunfire and cannon flare. He would have fought for all he was worth, galvanizing his knowledge of warfare and defense into one last-ditch effort to survive. Crockett no doubt clambered to a post and started shooting, helping expel the initial surge which fell back, taking heavy casualties, but then resurged. Mexican sergeants and officers flogged any recruits trying to retreat, herding new formations on ahead.

40

With a second formation hammering hard at the north wall, forces also pinched like talons from the south and the east, while Santa Anna’s reserves, and his band, lay in wait by the northern battery.

41

Desperate columns, taking incessant grapeshot and ducking under the dreadful whir and whistle of flaming metal flying overhead, convened near the north wall. Crockett and his riflemen fired and reloaded as fast as they could work, grabbing rifle after rifle until all their pieces were empty and they were forced to stop and reload once more, their efforts forcing the oncoming column to angle out and away, toward the southwest corner.

42

A third advance came, and now the Mexicans were mounting the ladders, redoubling their efforts. Two other ragged lines at the east and northwest had breached and reformed, and now all merged into a single swarming mass at the base of the north wall. They were too close for cannon fire, but shotgun spray and rifle bullets peppered them from above. Still, they came, now scaling the rough woodwork repairs that latticed the outer walls. They placed ladders, and into the face of direct fire, up and over they went, droves upon droves of men hoisting each other from the bottom, climbing over one another, stepping on each other’s arms and hands and heads. Soon, the defenders at the top could no longer reload fast enough to repel the sheer numbers mounting the parapet, and they found themselves engaged in hand-to-hand combat, stabbing viciously with bayonets and knives. José Enrique de la Pena was there under Santa Anna’s command, and he remembered the scene vividly:

The sharp reports of the rifles, the whistling of bullets, the groans of the wounded, the cursing of the men, the sighs and anguished cries of the dying . . . the noise of the instruments of war, and the insubordinate shouts of the attackers, who climbed vigorously, bewildered all . . . The shouting of those being attacked was no less loud and from the beginning had pierced our ears with desperate, terrible cries of alarm in a language we did not understand.

43

The Alamo had been breached.

As the north wall fell and the Texians retreated under the onslaught, the fight turned inward, with defenders shooting anything that resembled a Mexican uniform, brandishing tomahawks and long knives, hacking and stabbing wildly with bayonets. Mexicans poured over the south wall as defenders retreated to the open courtyard, while some, hemmed in on two sides now and staring down certain death, leapt from their positions on the palisade or squirted through the corner of the cattle pen.

44

Those who managed to escape were summarily ridden down and slain point-blank in the ditches and chaparral surrounding the fort by Ramirez y Sesma’s men, who killed them with lances.

45

Crockett ’s desire to die out in the open air may have crossed his mind, but he had his hands full fending off the newly breached south wall and the hundreds of Mexicans streaming in. Now soldiers outside used massive timber to bash and ramrod the gates, also breaking through any and all windows and doors. Crockett and his riflemen stood in defiance as long as they could, “then withdrew into the chapel.”

46