American Legend: The Real-Life Adventures of David Crockett (41 page)

Read American Legend: The Real-Life Adventures of David Crockett Online

Authors: Buddy Levy

Tags: #Legislators - United States, #Political, #Crockett, #Frontier and Pioneer Life - Tennessee, #Military, #Legislators, #Tex.) - Siege, #Davy, #Alamo (San Antonio, #Pioneers, #Frontier and Pioneer Life, #Tex.), #Adventurers & Explorers, #United States, #Pioneers - Tennessee, #Historical, #1836, #Soldiers - United States, #General, #Tennessee, #Biography & Autobiography, #Soldiers, #Religious

The Mexicans moved room to room, blasting doors apart with the defenders’ own cannons, entering with bayonets brandished. Reaching the hospital rooms they found the sickly, weak, and debilitated men feebly attempting to defend themselves, the once-strong and fierce knife fighter Jim Bowie among them. He lay in his cot, beneath the covers, perhaps already unconscious, and he offered no resistance as the Mexicans stabbed him repeatedly, then fired on him at point-blank range, spattering his brains across the wall.

47

By now there remained only a handful of defenders still alive inside the Alamo walls, and the Mexicans had but to round them up and slaughter them one at a time. The chapel held the last defenders. The Mexicans blew the chapel open with cannon fire and pressed in, enveloping a small knot of six men who were now surrounded. David Crockett was among the last standing.

48

Santa Anna received news that the Alamo was secured, and soon he entered, scanning the dreadful slaughter in the first pink-orange embers of daylight. Perhaps forgetting the previous chant of

Degüello,

no quarter and no mercy, General Manuel Fernandez Castrillion brought forward Crockett and the others, whom he had ordered his reluctant soldiers to spare. Santa Anna took no time at all to scoff at Castrillion, waving him away “with a gesture of indignation,” and order the immediate execution of David Crockett and those who stood with him that cold morning. Nothing happened for a moment, and it appeared that the men might actually disobey their commander. They had seen enough killing, and these helpless men now posed no immediate threat. But in the dim twilight, the sky and air gunmetal cold, officers hoping to ingratiate themselves with their leader leapt forward, “and with swords in hand, fell upon these unfortunate, defenseless men just as a tiger leaps upon his prey. Though tortured before they were killed, these unfortunates died without complaining and without humiliating themselves before their torturers.”

49

David Crockett was dead.

BY THE TIME all the smoke had cleared and the bodies were counted, Santa Anna’s one-sided victory proved to have come at a very high cost—nearly 600 of his men had been wounded or killed. Commander in Chief Sam Houston marched toward the Alamo, realizing that the pleas from the fort had been legitimate, but by now of course it was too late. Houston took his own sweet time moving south, spending five entire days on a ride that should have taken just two, during which time he camped two nights on the Colorado.

50

On March 11, Fannin received two missives from Houston, the first confirming that the Alamo had fallen, the second ordering Fannin to withdraw, repositioning for defense at Victoria, on the Guadalupe.

51

He was also instructed to blow up the fortress before departing.

Fannin dallied, and his indolence cost him and his men dearly. Mexican General José de Urrea closed in quickly, catching Fannin in retreat on March 18 and surrounding him a day later out on the open plain. By the end of a daylong skirmish Fannin had suffered sixty losses compared to 200 Mexicans, but by the next morning Urrea received significant reinforcements, rendering Fannin and his men defenseless. When Urrea, a humane and decent general, called a ceasefire, Fannin believed he might convince his opponent to offer reasonable terms of surrender, but he had not reckoned on the wrath of Santa Anna, who reiterated his order that rebels and traitors be executed on the spot.

52

Urrea hated to do it, but after seizing all of Fannin’s weapons and ammunition, the sickened Mexican general marched Fannin and his men in four columns out onto the road under the guise of wood-gathering and a journey to Matamoros, and summarily leveled them with musket fire, finishing them off with bayonets and knives until 342 men were slain. A few dozen escaped to report the horrific event.

53

On April 21, 1836, Houston finally entered the fray, advancing on Santa Anna’s fatigued army which, with two recent decisive victories and blood still drying on their hands, understood Houston to be in full retreat mode. Instead, Houston marched two parallel but roughshod columns totaling some 900 men inflamed by the battle cries “Remember the Alamo!” and “Remember Goliad!” The surprise attack stunned Santa Anna and his exhausted troops, who were unprepared to defend themselves in soldierly fashion, and lapsed into panic and confusion.

54

Even Santa Anna himself—who had been sleeping—became disoriented, unable to give useful orders as the Texians advanced in battle frenzy. They continued to chant “Remember the Alamo, remember Goliad”; some were even said to cry out “Remember Crockett!” The attack was so sudden and unexpected that many of the Mexicans simply ran for their lives, but were thwarted by the bayou and the lines of Texians, who gunned them down.

55

The Battle of San Jacinto was really more of a slaughter, a revenge massacre for Santa Anna’s “no quarter” victories at the Alamo and Goliad. Men were shot attempting to swim away in the Buffalo Bayou, others ridden down and impaled with bayonets, and many were shot point-blank in the head. One Texian participant called it “the most awful slaughter”

56

he ever witnessed. It was over in just eighteen minutes. Houston had two horses shot from under him and his ankle shattered by a rifle ball, yet he could take solace in the fact that he’d captured the Napoleon of the West, when Santa Anna was finally rounded up and taken prisoner. Shrewdly realizing that the great general was more useful alive than dead, Houston would hold on to his prize until he could get what he wanted, which was the rest of Santa Anna’s army back in Mexico, on the other side of the Rio Grande.

57

As a result of his success at San Jacinto, Sam Houston joined his old friend from Tennessee, David Crockett, as a hero of Texian independence. Houston would live to be elected twice as the president of the new Republic of Texas and ultimately governor of the state—Crockett would live on as a legend.

58

Back home in Tennessee, it did not take long for the rumors of Crockett’s demise to arrive. In mid-April the

Niles Register,

quoting from the

New Orleans True American,

listed Crockett as having fallen with the fort: “Colonel David Crockett, his companion Jesse Benton, and Colonel Bonham of South Carolina, were among the number slain.”

59

Elizabeth would certainly not have been surprised: he had nearly died afield more than once, had tricked death time and again—she well knew the Christmas gunpowder story, the barrel-staves scrape, all the close calls. The stalwart, now twice-widowed woman knew how to keep scrapping when things got tough, and she would certainly have lowered her head and pressed forward. By early summer, tender and heartfelt letters of condolence began to find their way to her, canonizing the man she knew as well as anyone had—and knew as a man, not a legend. She had known his love for the outdoors, known him to be happiest when in nature, and she would have been especially moved by the letter she received from Isaac Jones of Lost Prairie, Arkansas, the man to whom Crockett had sold his watch, who returned the timepiece out of respect. Jones offered his sympathies, adding that with Crockett’s loss, “freedom has been deprived of one of her bravest sons . . . To bemoan his fate, is to pay tribute of greatful respect to nature—he seemed to be her son.”

60

Although Crockett failed to garner the coveted “league of land” or fortune for his family, Elizabeth was eventually granted his soldier’s share, and in 1854 she and a handful of family members and children followed his tracks from Tennessee to Texas, where they would live out their lives, and Crockett ’s dream, on the vast frontier.

61

Robert Patton Crockett, eldest son by Elizabeth, went earlier, heading to Texas in 1838 to volunteer his services in the army as his father had done. Elizabeth remained true to the memory of her husband, and was said to wear black until her own death, in 1860.

62

John Wesley Crockett followed his father’s trail to the United States Congress, where he served two consecutive terms beginning in 1837, winning the seat left open by the retired Adam Huntsman. John Wesley Crockett picked up where his obstinate father had left off, and, fittingly and ironically, in February of 1841, John Wesley drove through the passage of a land bill in many ways comparable to that which his father and Polk had compromised on back in 1829.

63

Apparently content with that punctuation mark on his father’s congressional career, John Wesley opted to retire at the end of his term in 1843.

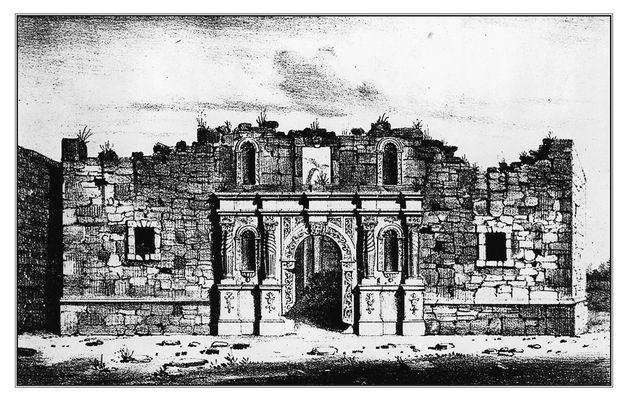

Ruins of the Church of the Alamo, San Antonio de Bexar. (Lithograph by C. B. Graham, after a drawing by Edward Everett. In government report by George W. Hughes, 1846, published as Senate Executive Document 32, 31st Congress. Daughters of the Republic of Texas Library, San Antonio.)

SANTA ANNA WOULD FINALLY SAY of the storming and subduing of the Alamo, which took just a single hour, “it was but a small affair.” He perused the carnage, hundreds of bodies strewn and smoldering, their “blackened and bloody faces disfigured by desperate death.”

64

After briefly praising his troops for their courage, he ordered the dead defenders piled into three heaps, two smallish mounds outside the grounds, and one large central pyre for those slain within the Alamo walls.

65

Soldiers then scoured the countryside to collect dry wood, lugging it back in carts. With sufficient wood gathered, soldiers mounded men and wood in piles, scattered smaller pieces of kindling about, doused the mass with flammable fluids, and pyre by pyre, set the Alamo defenders ablaze. The flames rose high and the fires burned all through the day and then into night, spitting and smoldering for three full days, until vultures began circling over the mission and crowds gathered around the ashes and embers.

66

Fragments of bones and the curling remnants of charred flesh lay among the ashes, and “grease that had exuded from the bodies saturated the earth for several feet beyond the ashes and smoldering mesquite faggots.”

67

Somewhere high above, David Crockett’s spirit drifted freely on the Texas wind, lofted away to immortality by the smoke of his funeral pyre.

Epilogue

DAVID CROCKETT’S DEATH AT THE ALAMO made him a martyr. In dying there and in that way, it was almost as if Crockett had said, “Well then, if I’m not going to make a fortune in this life—I might just as well become immortal and make my fortune in the next.” And that’s exactly what he did. Facts were shrouded in mythology almost immediately following the siege, as bogus reports began to circulate around Texas and abroad that Crockett had not fallen, but had been captured, taken prisoner, and brought to Mexico, where he was toiling away in a mine somewhere.

1

Crockett’s own publishers, Carey & Hart, were quick to capitalize on the fascination and uncertainty regarding the controversial frontiersman. Just two months after the fall of the Alamo, Philadelphia writer Richard Penn Smith wrote, and Carey & Hart published, the wholly fictional and anonymously written

Col. Crockett’s Exploits and Adventures in Texas.

The first-person narrative, ostensibly penned by Crockett, included a very convincing preface, signed by Alex J. Dumas, claiming that the contents were the “authentic diary” of David Crockett discovered among the ruins at the Alamo by a Mexican general who subsequently died at San Jacinto.

2

Staring at an unsold pile of Crockett ’s legitimate (if cobbled together and poorly written)

Tour to the North and Down East,

Carey & Hart hurried

Texas Exploits

off to press, and it was considered genuine for many years, selling thousands of copies.

3

It was not until 1884 that the fabrication was exposed in print, but by that time generations had swallowed the diary as authentic, accepting and incorporating the tales and exploits into lore. A gullible public appeared more than ready to devour these fictions as memoir, and the farce became a virtual keystone on which the Crockett legend would be built.