Among Flowers (5 page)

Authors: Jamaica Kincaid

Two things happened as I was sitting inside by the fire drinking my beer: A beautiful woman, with naturally glossed, long black hair, saw my own braided-into-cornrow hair and she found it so appealing that she came and sat beside me to touch my hair. She picked up my long plaits and turned them over and over, and using gestures, she asked if I could make her own hair look like mine. I did not know how to tell her that my hairdo, which she liked so much, was made possible by weaving into my own hair the real hair of a woman from a part of the world that was quite like her own. And then when the rain came, Dan had gone to make sure that all our things were protected from getting wet. When he returned, I noticed a big, dull maroon-colored spot on his calf. I thought it was a peculiar bruise, but it was a leech enjoying life on Dan's leg. We all shuddered, Nepalese and visitors alike, with varying intensity, at the sight of it.

The rain continued through dinner. Our dining tent leaked. We sat at our table, set with knife, fork, spoon, and paper napkin, and kept shifting around to avoid the water coming through our tent, eating by candlelight when from outside came the sounds of digging; it was our Sherpas making trenches that would guide the water away from our sleeping tents. It was so kind, so considerate. I had not thought of the possibility of drowning in my sleeping bag while traveling in the Himalaya.

That next morning (it was the eighth of October, a Tuesday, but it had no meaning for me, no usual meaning, it was another day), we were woken up with a cup of tea. After washing, eating breakfast, and packing up, we were off at seven-thirty. It was eighty-nine degrees Fahrenheit as we started out and the sky overhead was that magical blue innocent of clouds, and clear, though over in the distance, a thick milk-white substanceâcloudsâcontinued to hide Makalu from my sight. A mile or so on, I would round a bend, and unless I came this way again, I would have missed my chance to see a natural wonder of the world, a wonder I had not known of before. It was then I had a new feeling, a feeling I had never had before. It was something like fear, but I was not actually afraid; it was something like alienation, but I didn't feel apart from the immediate world around me or apart from my friends, Dan and Sue and Bleddyn. I had been away from my home less than a week, I had two children, I could see their faces in my mind's eye, I had come on this journey all because of the love of my garden. The garden, indeed, for here was Dan furiously trying to photograph a bundle of fodder a man was carrying on his back. The fodder turned out to be

Viburnum cylindricum,

a plant he treasures in his garden in Kingston, Washington. It is a beautiful

Viburnum,

with lance-shaped leaves that are deeply veined and white flowers loosely clustered together. It would be too tender for me to grow in Vermont but right for his climate. Dan followed the man for a little while, clicking away with his camera, recording this fact: a garden treasure for him is animal fodder in its native land.

Our porters had been late with our luggage the day before and so when we got to our campsite in Chichila we couldn't change out of hiking clothes right away, and that had caused some irritation and the beginning of our little complaints. That next morning Dan suggested that we pack a change of clothes in our day pack and so not be dependent on the porters for dry clothes when we got into camp. He had remembered from his last trip here that they had a rhythm of their own: it all started out well, but eventually there would be some problem and porters had to be let go and new ones hired in the next village. Now as we walked on toward Num, the town where we would spend the night, a small worry cropped up: our porters seemed not to be as well-disciplined as the other porters with the other groups. They lagged behind and sometimes would disappear completely. We were in open land. The sky could not be more blue. The sun was a hot I had never experienced; it seemed to penetrate into my skin, going in one way and coming out the other. We marched on, sometimes passing the porters, but then they would rush past us carrying our bags, our tents, our chairs and tables, our food, our everything at an incredible speed. When we passed the porters, our hearts sank; when they passed us and rushed on ahead, we thought of the day's end and our nice tents with sleeping bags waiting for us. We came to a little village that appeared to be the Himalayan equivalent of a truck stop. There was a shop, dark inside, and men were coming in and out. There was a lot of shouting and even drunkenness. It interested me greatly to know what was going on. Sunam would not let us linger to see anything or buy anything, but he had not so much control over the porters. We then descended into a forest the floor of which was littered with a chestnutlike fruit, but Dan and Bleddyn couldn't quite agree on what this was, and I could see it was because it had no interest for them. I saw a climbing fern and then I saw my first maple,

Acer campbellii.

It wasn't like the maples I am used to seeing, big-trunked, tall, and with leaves like a geometric illustration. It was slender and modest, and the leaves were only notched near the top, almost imperceptibly so. In the forest, the temperature fell to seventy-eight degrees Fahrenheit, and the cool was welcome. All around us we could hear the gurgle of water coming from somewhere and the ground on which we walked was soft with moisture. Dan was looking for another maple, not the

campbellii,

and he could not find it. He remembered from before that he had found it around where we were but now there was neither the tree nor seeds of it. However, he and Bleddyn found

Paris

and

Roscoea, Tricyrtis, Thalictrum,

and

Lithocarpus,

and something they said was fagaceous, but I had no idea what that could mean. Just outside Chichila they had found some

Rosa brunonii

in fruit, though they were not so very excited about that. We emerged from the forest back into the open sun, and I have to say that I began to flag then. At one o'clock we stopped for lunch in the village Muri. What made Muri a village, other than it said so on the map, I will never know. We ate lunch outside the one-room schoolhouse, a lunch that Cook had made inside the school. We had been walking for five and a half hours. It was eighty-nine degrees Fahrenheit. Many times during our walk we thought we would stop for lunch but we could never find a place that had enough flat space for Cook to make our meals, and water with which to cook our food, and then space for us all to spread out and eat. We ate our lunch, fresh vegetables and tinned fish, and some peopleâinhabitants from Muri or not, we could not knowâwatched us do so. Some of the children had hair that had lost its natural pigmentation; it had been black but had become blond, a sign that some essential nutrient was missing from their daily diet.

From our lunch spot, we could see Num in the distance. It was not far away at all. A couple of hours' walk and that was mostly downhill. We started out, in the usually gingerly fashion, and then soon were confidently marching along. We walked on paths, sometimes along places that could only accommodate one person passing at a time, so someone would step aside, squeezing themselves into the brush or into a substantial rock.

On the way to Num, we passed by a nicely built house, it looked like a domicile I was used to; it had a house, a barn, and some other outbuildings. This scene of house, barn, outbuildings, did not look prosperous; it looked more like toil and eking out an existence. It looked industrious. I stopped for a rest outside a building that looked like a place where the cows would be kept, and I enjoyed this scene of familiar domesticity. Not long after, while walking all by myself, Dan and Bleddyn in front of me, Sue behind me, I heard Sue let out a muted, sympathetic scream. From behind me, she could see that my back was covered with blood, my nice blue high-tech synthetic T-shirt was covered with my red bodily fluid. A careful search was made of my clothes and my body but the leech was not found, and this left me with the feeling similar to one I had experienced when I was young and living in New York City and was always afraid of drug addicts breaking into my apartment and stealing my things so that they could then go and buy the drugs they craved. My fear of leeches became way out of proportion to the danger they actually posed. Every step I took was more dangerous than the leech burying itself in my upper back. Dan took a picture of my bloodied back and later when I took off the shirt, I was shocked at how much blood had stained its surface.

We got to Num, camped in the center of town, and sought out some beer. There was none at first, but then someone had some. The lack of readily available alcohol would come to be evidence of the presence of Maoists, but we did not know that then. The beer was warm. Num never, ever had ice. Num had no electricity. The beer was delicious. We found a seamstress and that was a good thing, for in the three days since we left Kathmandu we had shrunk. In fact, if there had not been a seamstress our clothes would be just fine. But I now see that we were aware that this would be our last chance to participate in life, that part of life in which you needed things done for you, luxurious things; your clothes needed tending, and your clothes were beyond necessary. We employed the seamstress to take in our underwear, fasten buttons, tighten pants, mend something or other. She did it well and we were very pleased.

That night there was a thunderstorm unlike any I had ever heard or lived through before. Dan and I were in our tent, tightly snuggled into our sleeping bags. It started to rain and the rain felt like water missiles directed at our tent. I was sure at any moment Dan and I would be drenched with water and part of our sleep routine would be sleeping in rain. But the tent remained upright. It was the thunder that was really frightening and remains so even in memory. The sound of the thunder was above and below us, far away and near at once, but whatever direction it came from, however near or far, it was not like any thunder I had ever experienced in real life or the imagination. There was that clapping and that roaring sound that I associate with thunder, but in this case it seemed to come from deep within the earth and the mountains that surrounded Num, and suggested that there was a more profound earth with mountains that was beyond Num. The warlike attack of rain and thunder continued throughout the night and I slept through it, and I was anxiously awake during it and then I slept through it again. We woke up to the continuing rain and then saw that we were completely locked into a thick mass of clouds. We could not see anything beyond twenty feet. We began to plan the day ahead, sitting around in Num, waiting for the weather to change days later, for the rain and the clouds that shut us in looked as if they would be that way forever. Books to be read were set out, journals to be updated, little bits of gossip to be retrieved from the depths of our brains. At about ten o'clock, the rain stopped falling, the clouds began to lift, dissolving into tiny wisps, and then the sun came out and shone with a brightness that seemed as if it had been just newly made. The whole transformation was in five minutes, from frightening and wet gloom, to hot sun and bright dry. Camp was immediately closed up and we were on our way again. We said goodbye to the campers we had met at the beginning in Tumlingtar, the ones from Spain and Germany and France. They were going off to Base Camp Makalu and would get there in seven days. They went right, we went left, and I had no thought of ever seeing them again.

W

e left the village of Num at half past ten, the day showing almost no sign of the storm or whatever it was that had gone on during the night. We exited the village by going through someone's backyard. They waved at us, calling out the usual Nepalese greeting, “

Nemaste,

” the equivalent of “Good day,” Sunam had told me. It was a simple enough greeting, but I couldn't pronounce it properly. I never succeeded in getting myself to say it just the way I had heard it. We started going down, and this as usual meant that sometime before the day was over we would be going up. After three days, I knew with fixed certainty that to go up would lead to going down and vice versa. Up was always so hard and I never greeted it with any pleasure. Down became so hard that at the end of our journey, it took me four weeks for my knees to recover. Still, if we were to find anything worth growing in our gardens (this especially applied to me, since I lived in the coldest garden zone) we would have to go up.

I believe I was so glad to be on the path again, walking and not sitting or lying while a terrific storm, a storm, the fierceness of which I was not familiar, raged around me. In any case the going down seemed like not much to me. We had been mostly going up the day before and had gotten up to six thousand feet. Going up had been very hard, so hard that I began to think it a definition of real mountain climbing. It is not. The thing that I had not yet gotten used to was this: behind every rising was another one, higher and then higher it went. The ease with which I was used to going anywhere and everywhere had sunk deep into me. If I wanted to be someplace, I only had to find a way of transporting myself there. The idea that I had to actually get myself from one point to the other, through my own effort, was hard to take in then and hard to take in even now, months later, as I write this. But what had I imagined when I set out to do this? I had thought I would walk of course, I just did not understand the kind of walking that was required of me. And so it was that day, our fourth day out, I felt that my legs were adjusting to this walk, this path, that cut through huge slippery rocks and fallen tree trunks. I walked carefully, I had to, a couple of times; and I fell flat on my bottom because I had made a misjudgment in my steps.

And then suddenly again, there was that dramatic, magical change that I was fast getting used to. We had started out, just after the rain, and it was still chilly, so much so, that we bundled up in sweaters. Suddenly it was hot. We had gone from a moist, cold, dark forest into open woodland. Suddenly it was so hot that Dan wished for a secluded spot, where there was a stream that flowed into a pool so that he could take a bath. He did not find the two together. As we walked along in that whole forest, far away from everything in the world, secluded spot and stream that flowed into a pool never did meet up. Perhaps to make up for not finding such a thing, we walked into a world of butterflies. At first, there were only bright yellow ones, dancing in the blue clear air just above our heads and in front of our faces, and there were many of them, as if someone or something nearby did nothing but produce such wonders. But then many other different-colored ones came by. And they came in combinations of colors that are always so startling when you find them in nature, and only in nature are such combinations of colors, maroon and green, red and gold, red with black, blue and gray, aqua blue and black, that never seem garish. I had a camera with me but I had no interest in photographing them. I couldn't anyway, they were never still. This was such a pleasant antidote to the leech of the day before. I never did run into such a sight again, a swarm of so many different butterflies, but the leech was a constant worry.

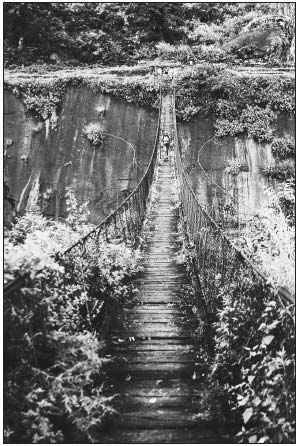

Author crossing one of the precarious bridges spanning the Arun River

Eventually, we could see the Arun River in the distance. We could also see the bridge over which we would cross it. That first bridge was a pleasant dream compared to some of the bridges I had to cross later, but the Arun at that point was wide and probably deep right there, and the bridge was narrow and long and I had never crossed such a bridge before. It was just before we crossed the bridge that I saw some Nepali script and a drawing of a star (as in red star) in bright red ink on the concrete foundation of the bridge. Maoists, I thought, at last here they are, this is a sign of them. They had forever been on my mind; I had weighed their presence and activities in Nepal before I came. Before I came, Dan had told me they were not killing foreigners and instead of saying back to him they are killing people, so we mustn't go, I was only too glad to be a foreigner and so become exempt from their wrath. Still they were killing people, and I have noticed that when someone starts killing people, though at first they draw a line at the kind of people they will kill, eventually that line gets erased as they start killing some other people. I can't really take the word of people who will kill their countrymen but not me. I only believed Dan because I wanted to, in truth I didn't believe Dan at all. I was afraid that if I ran into the Maoists they would kill me. Still, the thought of the garden and to see growing in it things that I had seen in their natural habitat, to see the surface of the earth stilled, far away from where I am from, perhaps I would be lucky and see only the writings of the Maoists, perhaps I would never, ever see them at all.

I crossed the Arun River on that bridge. It was exactly half past twelve and we were at an altitude of 2,044 feet. Everyone was very encouraging. They had all done it before. Sunam and Mingma and Thile did not laugh at me; the porters did not laugh at me. Sunam waited for me at the other end and told me how brave I had been to do it. He was very kind to me and was always helping me to put the best face on everything I did awkwardly. Early on he had shown me our route on the map, and I must have looked strange for he said, with much forced cheeriness, that it would be very beautiful, as if he knew to someone like me the word was a sedative. Once, when I had, after a great deal of huffing and puffing, got to the top of a ridge, only to see yet another ridge and then beyond that a huge mountain, I asked him the name of the mountain I saw ahead of me. He said, “That is not a mountain, that is a hill and it has no name.” Exactly what he said. But of course, there are no hills in Nepal, there are no meadows, there are no valleys, there are only things that might be called hills and meadows and valleys, all of them little interruptions, little distractions in a landscape that is all mountain. I knew there were no hills but when he said that, I became truly silent. Earlier I had asked him about the red markings on the bridge, I had wondered out loud to him (though I whispered it) if that was a sign of Maoists. He said, no, it was just the Nepalese people expressing their opinions in the recent election. Of course, some of those opinions in the recent elections were those of the Maoists. I knew that but I did not say this to him. And another reason I had to take everything he said with a large grain of salt: Whenever people we met seemed to be talking about us, though me in particular (sometimes it was the color of my skin, sometimes it was my hairstyle), if we asked Sunam what they were saying, he would say he didn't understand their language. He would say that they were speaking in a local language that he didn't understand. The mystery of what Sunam did and did not understand became a source of much amusement. What are they saying? we would ask. I don't understand, Sunam would reply. A joke between Dan and me was: “What are they saying?â[a short pause]âI don't understand,” and this would make us laugh until we ached in the last places left in our bodies that were not in pain from our exertions.

At half past one and at an altitude of 3,030 feet and temperature ninety-six degrees Fahrenheit, we stopped and had lunch in a place that was not even on the map. It was on the tiny plateau of a steep climb we had just made. It took us an hour to get there from the crossing of the Arun River and it was less than half a mile. Of course Cook and his assistants were there already when we arrived and they had our hot beverage waiting for us. We had a lunch of potato salad, mushrooms, and boiled melon. A young woman sat on the porch of her house, lovingly combing her own very beautiful, long black hair, trying to make it free of lice. From her exquisite strokes, I could see that she had much practice, which meant that it would never be so. She looked very sad and lost in that way people do when they are doing a good thing but only for their own benefit.

We walked through a neatly arranged village with houses made of wood and painted white but it was too early to stop and, in any case, the village seemed to take up all the flat spaces where we could camp. It was hot, tropical, and I recognized plants from Mexico: bougainvillea,

Dahlia,

marigold, and poinsettia especially. Every house was surrounded by a food garden, and though I know that is unusual, a food garden, the way they grew food, squash vines, for instance, carefully trellised and then allowed to run onto the roof of a nearby building, was so beautiful, it became a garden. And in making this observation, I was reminded again that the Garden of Eden is our ideal and even our idyll, the place where food and flowers are one. After that, food is agriculture and flowers are horticulture all by themselves. We try to make food beautiful and we try to make flowers useful, but it seems to me that this can never be completely so. In this village almost every building had something written on it in red paint and the drawing of the sun in much the same way I had seen on the bridge earlier. I did not ask Sunam where we were, for I suspected it fell into the category of a place with no name, a place where he did not understand the language. We walked on and spent the night on the school grounds of the next village, a village called Hedangna. That village had a center concentrated around a little fountain of water, built not for beauty but for necessity. From the school yard where we camped, we were surrounded by the most stunning view of a massive side of a cliff from which poured white, stiff bands of water. They were waterfalls, but they didn't seem to fall in the way I was used to. It looked as if they had been set down there on purpose, so constant was the flow. It was so stunningly beautiful in its cruelty. For the people who looked at it, myself included at that moment, could die from want of it. It is very hard to get water for use in this place where there was so much of it. Water could be seen everywhere, but difficult to harness for human uses. After a few days, we looked more like the people who lived in this place than as if we did not. We looked as if we longed to bathe and I smelled that way too. As if to remind us of how the day had begun, just before the sun vanished, not set, vanished, a rainbow suddenly arced out of the clouds that were keeping the tops of the mountains ahead of us in a shroud. For all of that, we calculated that we had walked three miles that day, we were only three miles away from Num, and yet it was another world altogether. As if I was looking, in a manner of speaking, at a set of pictures, of the same event but from different angles and seen at different times of the day. Num was only three miles away. I could even see it across the deep valley from which I had come, but the distance seemed imagined even though I could actually see it.

That night, we were surrounded by more children and adults than usual, and Sunam told me not use my satellite telephone. That was how I knew he was worried the Maoists were around. They came to see us, boys and girls in equal number, so it seemed to me; a man carrying a baby, but he could not have been its father, he seemed so young. An old woman came over to me and literally examined me. She picked up my arm and peered into my eyes and touched and poked my skin; then felt my braids and loudly counted them out in her language, a language which Sunam, I am grateful to say now, told me he did not understand. We went to sleep in our tents, Sue and Bleddyn in theirs, Dan and I in ours. Dan read some of a book he said was very bad; I tried to read my Smythe but found I could not concentrate on his adventure, for I was having my own.

That next morning we left our camp at half past seven. It was eighty-three degrees Fahrenheit. We had eaten a breakfast of rice porridge and omelet with onions. How good everything tasted. How good everything looked. The world in which I was living, that is, the world of serious mountains, the highest peaks in the world, over the horizon, if only I would just walk to them, the world of the most beautiful flowers to be grown in my garden, if only I would just walk to where they were growing. I was trying to do so. That morning, I could see that on the top of one of Sunam's “hills with no name” there was snow. The day before, Bleddyn had said to me that I should try to find

Actaea acuminata

because someone named Jamie would give me Brownie points. Dan said we were too low for finding this; Bleddyn said, yes, but soon we would be. I, of course, would have no idea what this plant is even if it were my nose itself. Still, I thought I would look; and much to Dan's and Bleddyn's annoyance, would always say, “What is this?” in my most studentlike voice possible. They were not pleased and I noted they were always way ahead, way out of earshot of me. They found an

Amorphophallus

at an altitude of 4,490 feet and it had seed, which they collected. And that was exciting, though mostly to me, for I had never found an

Amorphophallus

before. I had never even thought of this plant before. It looked like a jack-in-the-pulpit except that the spathe stood upright. Bleddyn thought there was sure to be some

Daphne bholua

growing right around where we were. But we could not find any. Then we came upon a village, again not one found on the map, and there in the yard of one of the houses were sheets of paper hung up on a clothesline, presumably to dry them. Dan and Bleddyn were very excited by this, for

Daphne bholua

is the plant often used for making paper. They ran to the man's house to buy some of the sheets of paper and he must have been very surprised by the sudden increase in his business, but he didn't show, at least not so that I could tell. Dan bought twenty-five sheets, I bought twelve sheets, Bleddyn bought quite a lot because he needed the paper to dry the leaves of specimens he was collecting. After our little shopping spree (and it did feel wonderful to buy something), the burden of which we simply passed on to our porters, there ensued a small disagreement between Dan and Bleddyn over whether the paper was made of

Daphne bholua

or

Edgeworthia gardneri

. This paper, by the way, was not some exotic thing being made for the use of people far away. It was being made for everyday use by the people in the surrounding area. It made me think of a beautiful young woman I had met the day before in the village of Hedangna. She was returning home to her village with a bag of salt on her back. She had gone to Hile, a big town that has bus service to Kathmandu, and purchased a load of salt. It was six days' walk from her village of Ritak, a village way up near the Tibetan border, to Hile and six days back. She carried with her a little pot and some rice and a thin foam-rubber mat. Often we would pass people going in one direction or the other (though, when they were going in our direction, they passed us easily) who carried on their backs a pot and grain of some kind and their foam mattress; sometimes we passed them cooking their food, sometimes we passed people asleep in the path, as if they couldn't go one step further and just lay down where sleep overcame them.