Among Flowers (6 page)

Authors: Jamaica Kincaid

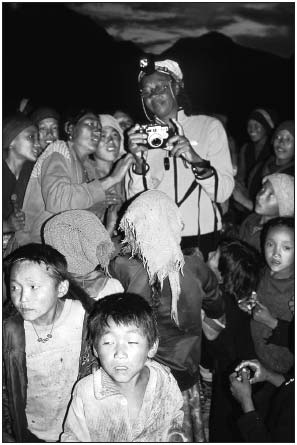

The author's digital camera offers villagers a rare glimpse of their own images.

We were walking now in wide, open, rocky meadows. For a while we walked along a dangerous ledge and there were lots of sighs, on my part. I saw a beautiful yellow

Hibiscus

in bloom; it looked somewhat like

Abelmoschus manihot,

but if it was that, it was the most beautiful form of it I have ever seen. It was a bright, glistening yellow and the blooms were huge. I never found any seed on it. Then we were in deep, moist shade, not exactly a forest, but a shady enough place for there to be found

Codonopsis.

We could smell it though it could not be found immediately. Eventually Bleddyn found a plant with some seed. It was ninety-six degrees Fahrenheit when we stopped to eat our delicious lunch of tinned baked beans, luncheon meat, and spinach. We stopped near a stream that was rushing downhill to meet the Arun, and we sat in it in a place where it made a pool, with all our clothes on.

That afternoon we crossed the Arun River four times, and three of the four bridges were quite sound ones. The one that wasn't I dealt with quietly. That afternoon also we saw some white-haired monkeys way above us in trees, and they made the most wonderful sounds to each other. I was so happy to see them; and this suspicious thought crossed my mind, that I was happy to see them because to see them is to claim them. Claiming, after all, was the overriding aim of my journey. Dan showed me a vine with grapelike leaves and stems covered with golden hairs. It was

Clematis buchananiana,

something new to me. That particular plant had no seed, and though we came across it many times, we never found any with seed and this even I regret.

By the time we made our final crossing of the Arun for the day, we were tired. We wanted to stop and make camp but Sunam said not then. We passed through rice paddies, and untended boggy places. We saw much marijuana growing wild, we saw people smoking the marijuana. Finally, at half past four, seventy-nine degrees Fahrenheit, 3,570 feet altitude, we came to the village of Uwa, the place where we would spend the night and a village under complete Maoist control.

The minute we walked into the village we could see them. There were banners hanging from house to house, and on the banners were portraits of a red sun and, I assume, the same sayings we had seen on the bridge. Sunam had actually reached the village an hour before we did. He usually went ahead of us to make sure our things were all set up for our arrival. But when we got to Uwa, one hour later, the porters were standing around with their burdens at their feet and Sunam was nowhere to be seen. He was actually in negotiations with the head Maoist. The head Maoist either couldn't or wouldn't give us permission to spend the night. There were many consultations. Finally we had to give them four thousand rupees, and at almost six o'clock we were allowed to go and make camp on the school grounds. To get to the school grounds we had to thread carefully through a rice paddy, carefully because we didn't want to ruin the crop and because we didn't want to get our shoes wet. That was done well enough, and we were just about to sink into the deliciousness of the danger we were in, when we realized our shoes were crawling with leeches that were eagerly burrowing into our thick hiking socks, trying to get some of our very expensive first-world blood. I shrieked of course, then took off my shoes and socks, then searched all the parts of my body that I could and asked Sue to search the parts of my body that I could not. She did and I did the same for her.

Things began to look grim. Sunam thought it would be best if he kept my satellite phone. The Maoist had told him that we would not be allowed to pass on through the village. The four thousand rupees were only for spending the night. We began to think of alternate routes. Sunam really began to think of alternate routes. Around that time, Sue and Bleddyn became Welsh and Dan and I became Canadians. Until then, I would never have dreamt of calling myself anything other than American. But the Maoists had told Sunam that President Powell had just been to Kathmandu and denounced them as terrorists, and that had made them very angry with President Powell. I had my own reasons to be angry with President Powell too. In any case I had noticed that all of the bridges I walked on to cross from one side of the Arun to the other had a little notice bolted onto the entrance, thanking a donor for the bridge. The countries mentioned were either Canada or Sweden. I had no idea how familiar Maoists were with people from Canada and Sweden. Canada seemed so broad, non-particular, open-minded. I decided, that if asked, I would say I was Canadian. I didn't feel ashamed at all.

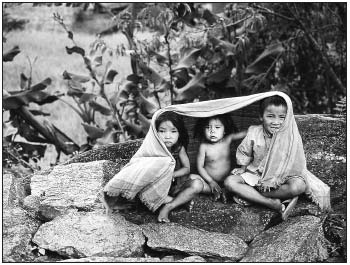

Village children

Whenever we had stopped to spend the night in a village, no sooner had we arrived then it seemed all the children in the neighborhood had come to stare at us. A few adults would come too, but mostly it would be children and they would stare at us as we cleaned ourselves, ate, went to bathroom (a little tent that we carried with us and was almost always the first tent to be set up wherever we were), even just sitting around reading. In this village no one came to look at us. All the children seemed to have walked up to a ledge that was right above us, and they climbed into the trees and began to make the sounds that some monkeys, who were also above us and in the trees, were making. It was meant to disturb us but it didn't at all. Nothing could be more disturbing than sleeping in a village under the control of people who may or may not let you live.

The village was situated in a rather strange place and there must be a good reason why people settled in just that spot. It was surrounded on all four sides by high steep cliffs. It was more like a dam, a place made for storing things, than a place to live. It had three openings through which people could come and go. But the cliffs were so high that they shrank even the vast Himalayan sky when seen from the village. That night we did the usual leech check. There was no laughter from our tents. We got up the next morning with the usual tea brought to us by Cook's assistant and an unusual amount of anxiety. Would they let us proceed or send us back? They let us go. Sunam gave them some more rupees, how much more, he wouldn't say. He made them give him a receipt to show to the other Maoists, if we should meet them, that he had already paid what could be made to seem like a toll, but Dan said with surprising anger, that it was extortion. Sunam had learned from someone that we should avoid spending the night or even going near the village we had planned on spending the night in because the people who controlled that village were even more committed to Maoism and took even stronger objection to the words President Powell had spoken in Kathmandu.

We headed out of Uwa at half past seven, so very glad to be leaving. No one spoke to us, not even to say the usual

Nemaste!

What a great hurry we were in. And we started up again, going up away from the Arun. It was good to be up but by going up high so early in the day, it meant something bad for Bleddyn. He had wanted to take a short hike up the Barun River and collect some seeds. How disappointed he was to see it, a thin streak of milky white coming down the mountain and ending in the Arun, which was way below us. He cursed the Maoists. We had been walking for six days now and there had been nothing substantial to collect. Nothing for me anyway. I would have done this, even if I had not been interested in the garden. Just to see the earth crumpling itself upward, just to experience the physical world as an unending series of verticals going up and then going downâwith everything horizontal, or even diagonal, being only a way of making this essentially vertical world a little simplerâmade me quiet. I saw the people and I took them in, but I made no notes on them, no description of their physical being since I could see that they could not do the same to me. I can and will say that I saw people who looked as if they came from the south (that would be India) and people who looked as if they came from the north (that would be Tibet). I saw some people who were Hindus (they were the same people who looked as if they came from the south), and I saw some people who were Buddhists (they were the same people who looked as if they came from the north).

As usual, we were walking along a ledge and a false step in the wrong direction could land any one of the four of us a few hundred feet down, either in the crown of trees or on sheer rock, for sometimes below us was thick forest, or sheer cliffs at other times. We stopped for lunch after one o'clock. The Arun was in full view and so was the Barun running into it. Even from so far above we could hear the roar of their waters. We stopped for lunch and it was memorable to me because that was the last time we had bread. For dessert, we had toast with marmalade and tea. It was the best toast and marmalade I had ever had, and when eating it I thought, This is all I'll eat for the rest of the time I am here. But when I requested it that night for dinner, I was told that the last of the bread had been eaten at lunch. It dawned on me then that requests were out, and I stopped asking for anything with the expectation that I would receive what I asked for. On again we marched after lunch, feeling a lot better because we could see our village in the distance and also because the collecting was becoming exciting, at least for any gardener who lives in at least two zones warmer than the one in which I make my garden. We were at an altitude of a little under six thousand feet and among the things Dan and Bleddyn collected were some

Hydrangea aspera

subsp.

strigosa, Boehmeria rugulosa, Costus

sp.,

Acer

(maple),

Paris polyphylla, Woodwardia

sp.,

Anemone vitifolia, Rubus lineatus.

It was about three o'clock when we arrived in the village, feeling pleased with ourselves for having avoided the Maoists, but something made Sunam change our camping spot. We had met a man who had just lost the tips of three of his fingers on the left hand. Someone must have told him we were coming for he was waiting for us with his hand outstretched, and he was crying. Dan, who always carries a little first-aid kit in his backpack, cleaned the wound and then put some Mercurochrome and a Band-Aid on the man's fingers. We had a little debate over whether to give him any of our Tylenol to relieve him of pain right away since we could not part with enough that might give him some comfort for many days. This ended with Sunam telling us that the village would not be where we would spend the night. We would have to march on a little further up above the village. Whatever he learned about our presence in the village, he never told us. We just were told that we would be camping a little higher up. We then took a road out of the village, going around it, not through it, and seeing some beautiful houses made of clay, painted white with some kind of stencil decoration around the windows and doors. I had seen something similar two nights ago when we stayed in the village of Hedangna, but there the stencil was done in the color brown while here it was done in blue. Bleddyn came across a pink

Convolvulus,

whose fragrance we could smell long before we saw it. But the

Convolvulus

had no seeds and, after the botonists lamented that fact, we just walked on and hoped to find it somewhere else with seed. We saw it twice again but always it was in flower, never having any seed.

Our way now, having left the village, was a steep walk up a landscape that had not so long ago collapsed. We had to climb up and then cross over a recently ravaged hillside (in any other place, it would be a mountainside), that had perhaps not too long ago been the result of a landslide. The evidence of landslides was everywhere, as if proving what goes up must come down is necessary. We, and by this I mean Sue, Bleddyn, Dan, and me, expressed irritation at this with varying intensity (Dan and Bleddyn minor, Sue almost minor, me loudly) and then marched on. Two men, dragging long thick trunks of bamboo attached to porters' straps wrapped around their foreheads, passed us as they were going the other way. They seemed to take our presence for granted, as if they knew about us before they saw us, or as if our presence was typical, or as if we did not matter at all. We marched on; by this juncture we were marchingâthe leisureliness of walking was not possible once we came in contact with the Maoists. When we got to the top, as usual, it was not at the place of destination. What had seemed to us as the top of the mountain was only the place where the avalanche began. The mountain continued up and it was as if the face of the mountain had decided to fall down starting in its middle. We had to go up some more because, for one thing, Cook, who was always ahead of usâhe could walk so fastâcould not find any water coming out of the mountain. And also we needed to find some level ground on which to cast our tents, forming our little community of the needy, dependent, plant collectors and the Nepalese people, whose support we could not do without. We kept going up, each turn up above seeming to hold the desirable flatness and water too, for how could that not be so when everywhere we looked we could see a milky white and stiffly vertical flowing line of a waterfall. But Cook went flying up and then went flying down to Sunam, and there were consultations. On our way up, past the place where the avalanche began, we met a herdsman, though before that we had met his cows. At first we made way for the cows because we thought we were in the cows' home and perhaps we should be respectful of them. But the cows remained so cowlike, stubborn and potentially dangerous, if you only considered their horns, and in this case

they

seemed to really consider their horns. The herdsman managed them beautifully, guiding them down and away from us, taking them into the steep bush-covered slopes away from the path they were used to traveling, just to keep us calm. I would not have thought about this incident of the herdsman and his cows again but I saw him the night after this and three nights after this again far away, for me, from all these difficulties.