Among the Bohemians (45 page)

Read Among the Bohemians Online

Authors: Virginia Nicholson

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Social History, #Art, #Individual Artists, #Monographs, #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural

1. I have never desired and will never desire anything else but happiness.

2. Happiness is the feeling given by the consciousness of absolute freedom.

3. No one can be free so long as he has material possessions.

4. Therefore nomadic life rather than settled.

But in the end Brenan was defeated by hardship.

He never reached China, nor fulfilled his ambition to follow in the steps of Marco Polo and join a

nomad tribe in Outer Mongolia.

Nevertheless, the journey was a liberation.

Radley School, the Home Counties, his parents, material gain, bourgeois values – all were left behind as he walked slowly eastwards beside his donkey, with his cartload of poetry and mind-altering substances.

This was travel for travel’s sake, not a means of getting somewhere, or a holiday, or even an exile, but a way of life in itself.

*

Such slow progress appealed to primitive instincts.

The purist disdained the aid of wheels; walking had all the advantages.

It was exhilarating; it revived the heart-rate, the appetite and the intellect.

The finer points of churches and inns rewarded one’s leisurely pace; natural beauties enhanced one’s pleasure.

Gerald Brenan and his generation were much influenced by W.

H.

Davies’s

Autobiography of a Super-Tramp

(1908).

Feeling hemmed in by the shackles of civilization, he was among many creative individuals who felt that the life of the lonely wayfarer held the answer to existence.

Magazines like

The New Age

idealised free love and the open road; the gypsy and the tramp became heroes to ardent Neo-pagans and nature lovers, who took up hiking and camping out with fervour.

For Paul Nash and his girlfriend planning a tour of the Lake District, part of the fun was the certainty that their vagabond life would electrify their conventional families.

They planned to walk or go in ‘a cart or buggy of some sort’, ‘putting up at odd inns, or sleeping under hedges’.

They paddled, and Paul sketched.

They saw starfish, curlews and cliffs, and picked wild raspberries.

There were wild woods and stony hills; ‘there was all that the heart of man could reasonably desire’.

Such adventures gave one a strong sense of identity with the ‘wandering minstrel, the troubadour, the gypsy.

One could be Villon, or Christian in

Pilgrim’s Progress,

Goethe or the Scholar Gypsy.

Gwen John and Dorelia McNeill set out on their great walking adventure in 1903.

With their paints and brushes they set sail for Bordeaux in August, intending to get to Rome.

For four months the ‘crazy walkers’ made their way on foot through western France, sleeping rough covered in portfolios of pictures for warmth, fending off attempts on their virtue, revelling in beautiful sunsets and distant views of the Pyrenees, painting portraits and singing for money, living off bread and grapes.

It was November before they reached Toulouse, by which time Rome seemed unattainable, so they gradually made their way back to Paris.

The poet Philip O’Connor, living a dependent life with his unsympathetic-sister, decided one day that he had had enough.

He robbed the gas meter

and departed with the proceeds.

For the next five months O’Connor tramped the roads of England, sleeping in barns or under haystacks, wretched and hungry but grimly determined to stay clear of ‘civilization’.

He met other vagrants, and scraped some pennies by collecting the money for a tramp wheeling a wind-up gramophone on a pram.

They shared a tent together, where the old fellow had a go at seducing him, ‘but the machinery was not suitable’.

After a friendly goodbye kiss O’Connor headed on his way:

Paul Nash sketched himself and Bunty

Odeh on their walking tour of Cumbria.

Walking had a saddening but soothing effect on me… I liked roads and moving… I liked very much the absence of the gymnastics of ‘social life’.

I felt ‘the truth’ would come too.

Tramps here and there were very nice to me…

Moreover tramps were spattered with the road, with the roughness of sleeping out, with the spiritual

finesse

hidden within the grossness arising from lack of employment; their eyes were wild, darting, aimed directly by the purposive intelligence, and there hovered nothing about them of that greasy, insulating caution of expression, tartiness of behaviour, meanness of gesture, incumbent upon hard workers for their daily bread…

I was moved and thrilled too by their smell of distance and space, one of the greatest spiritual elegancies available to man, which polishes him like a knife.

One man under his sky is an eternal image…

O’Connor got the boat to Ireland.

But in the busy streets of Dublin he panicked, began to feel he was going mad and presented himself at a lunatic asylum.

The doctor firmly rejected him – no chance of food and shelter there – so he went to the workhouse, but was forced into shovelling stones to make enough money for food.

The Salvation Army gave him shelter for a few days, and then got a friend to send him the fare home.

His adventures on the road were over.

*

That eternal image – one man under his sky – is ineradicable from the Bohemian landscape.

In his guise as the Toad, Augustus John, influenced by George Borrow and by his mentor John Sampson, ardently adopted the gypsy life, strongly identifying with those ‘children of nature’.

Augustus learnt their language, their customs, wore their clothes, admired their beauty and mystery, supported them against intolerance.

He was far from alone in this commitment, and indeed was to become a leading light of the Gypsy Lore Society, whose journal, launched in 1888, was the voice of a wonderful assortment of like-minded gypsophiles the world over.

For in a society increasingly dominated by inward-looking, bureaucratic capitalists, the gypsies’ lawless independence held a captivating glamour.

The visitations of Eastern European gypsies to England in the second half of the nineteenth century fuelled the ardour of stay-at-home dreamers to forsake comforts and set out on the roving life.

Around the turn of the century there was a ferment among writers and artists eager to sample gypsy life for themselves.

Titles began to appear like Gordon Stables’s

Leaves from the Log of a Gentleman Gypsy – In Wayside Camp and Caravan

(1891), Elisabeth von Arnim’s

The Caravanners

(1909), or Marion Russell’s

Five Women and a Caravan

(1911).

Such works extolled the ‘wee wayside inns’, bacon and eggs eaten in the open air, healthful slumber, and the feeling of being ‘at home with all Nature’.

I can never forget this first experience of sleeping in the open… [wrote Marion Russell].

The rustling of wild things in the wood near me, the softness and sweetness of the air, seemed to develop a mood which brought me into communion with Nature, and vague thoughts as to the meaning of things came in waves approaching, so that I almost grasped them, and then receded, leaving only a faint impression of their meaning… I had the first faint dawning of what the meaning of Eternity might be…

The caravan craze touched a significant sector of Bohemian society in search of eternity, birdsong and an economical holiday, if only for a week or two every summer.

Caravan-loads of artists began to appear on lanes across England, sometimes across France.

One could hire fully equipped caravans by the week for a progress around the New Forest, though it was more affordable, Robert Graves discovered, to borrow a horse-drawn van from the local baker.

In such a van he and Nancy and their three small children set off from Islip one August heading for the Sussex coast.

The reality didn’t match up to the ideal, for, mistaking them for real gypsies, some of the farmers whose land they tried to camp on were distinctly unwelcoming.

The van too proved to be of flimsy construction, causing one of the children to fall out and get hurt.

Then the weather conspired against them, and soon their wagon was draped with the baby’s damp nappies, impossible to dry in the downpour.

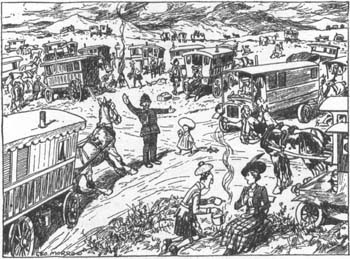

Gentleman gypsies mocked by

Punch,

19 june 19:1.

Evelyn Waugh had one of the worst holidays of his life sharing a caravan with a friend at Beckley near Oxford.

It rained and the vehicle leaked.

Waugh took himself off to the church and sat down to read Gibbon, then they walked to Oxford and got drunk.

He did not repeat the experiment.

But Waugh’s incorrigible friend Brian Howard, an unlikely candidate for the gypsy life, was in raptures over his caravan holiday in Scotland: ‘It’s more beautiful than words can describe, and I feel so well!

I cook; wash up;

wash myself in icy water in little burns; rise at 8; sleep at 10…’ In fact the gypsy life seems to have been particularly popular with the classier end of Bohemia; perhaps playing at Carmen held an illicit charm for the debutante that eluded the genuinely disadvantaged.

Another friend of Waugh’s, Lady Eleanor Smith, daughter of the Earl of Birkenhead, became obsessed by gypsydom.

She set aside her career as a fashionable gossip columnist to write first

Red Wagon

(1930), followed in quick succession by

Flamenco

(1931),

Tzigane

(1935) and

The Spanish House

(1938) – Brontё-esque novels pulsing with swarthy passions.

Flamenco

is the tale of a Spanish gypsy girl who tries in vain to expunge her Romany origins.

She brings up her child as a gentleman – but nothing can alter the fact that he has Romany blood in his veins, and Camila has no power to obliterate the memories of her former life:

She would [never] talk to him of life on the road, but of hunting, shooting, and books.

He would lose, she thought, much that was beautiful – the blaze of stars sprinkled thick across the sky, the harvest-moon… summer dawns… [etc.

etc.]… and for a moment she pitied him, until she thought of lashing bitter rain, of sleet that bit like the teeth of wolves, of empty bellies, and of bodies stiff and numb with weariness… and of the road, the accursed, damnable, seductive road that had no end, that sooner or later maimed and killed all those whom it had once enslaved.

*

The ineluctable advance of technology in the twentieth century changed the world for everybody.

Even the most uncompromising Bohemian could not ignore its onward march, while for many of an adventurous spirit the motor car and the aeroplane brought welcome opportunities to get further away, and faster.

Speed itself had a pure appeal for many artists who felt temperamentally challenged to take risks in all aspects of life.

When Stevenson wrote ‘Faster than fairies, faster than witches’ in 1885, train travel still seemed magical in its rapidity.

But by the first decades of the twentieth century even the

Train Bleu

had lost its ability to make one’s hair stand on end.

Being a passenger meant, too, to be passive.

The coming of the automobile at the beginning of the twentieth century provided the experience-hungry artist with a range of ever-escalating thrills that their predecessors could never have imagined.

By the mid-twenties a writer or artist who was not in financial difficulties might find themselves at the controls of their very own motor car, possessed of the ability to go where the spirit moved, and fast:

‘Glorious, stirring sight!’ murmured Toad, never offering to move.

‘The poetry of motion!

The

real

way to travel!

The

only

way to travel!

Here to-day – in next week to-morrow!

Villages skipped, towns and cities jumped – always somebody else’s horizon!

O bliss!

O poop-poop!

O my!

O my!’

His caravanning days over, Augustus John exchanged a picture for a new yellow Buick at the earliest opportunity.

After half an hour’s instruction, he piled in a group of friends and set off for Alderney Manor in bottom gear.

There was a small contretemps with a barrel organ, and they had to disentangle themselves from a train at one point on the journey down, but apart from this they arrived without incident – still in bottom gear.

After this there was no stopping Augustus.

His driving was to become legendary as, equipped with one bottle of gin and another of whisky, he speeded down England’s highways, oblivious to steamrollers, pedestrians, junctions and lampposts.

The Buick grew to be, as Michael Holroyd says, ‘a magnified version ofhimself’.

Though battered and dented, though its starting mechanism was temperamental and its action explosive, it nevertheless seemed indestructible.

Augustus ran his friends over, and got run over by his friends.

He barged into ploughed fields, over hedges and through closed gates.

Time and again he and Dorelia emerged unscathed from amid masses of twisted steel.

John and his car seemed invulnerable.