Among the Bohemians (46 page)

Read Among the Bohemians Online

Authors: Virginia Nicholson

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Social History, #Art, #Individual Artists, #Monographs, #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural

Motoring made so much possible that had seemed prohibitive in the past.

No longer confined to views in the immediate locality, an artist could load up easel and canvas and drive off in search of new landscapes, new motifs.

This was marvellous liberty; but even in those early days, the drawbacks of speed and convenience were becoming evident.

It began to dawn on Vanessa Bell that not only could she go where she wanted, but other motorists might also go where

they

wanted.

‘Now that everyone owns them one is never safe…’ So many unwelcome visitors drove up to Charleston that she had to paint a large notice and stick it up at the bottom of the track, saying:

To Charleston

OUT

Cars were wonderful, conceded Richard Aldington in his autobiography, but he too had reservations.

The activity of driving was in itself enervating, one missed everything there was to see, and its effects were already devastating the countryside:

England is a small country with a wonderful network of roads, so that three decades have already been long enough for the motor car to suburbanise most of the areas which industrialism had not touched.

It isn’t much fun to walk there

*

In 1929 Bunny Garnett took his first joy-ride in a two-seater biplane over the Huntingdonshire fens near his home.

The experience proved completely addictive, and three years later he wrote

A Rabbit in the Air

(1932), from notes that he kept while learning to fly:

The sense, first of power, and then of complete abandonment to the will of the machine, is wonderful.

The slowly rotating earth coming towards you as you hang over it, is a precious jewel; there is a feeling of freedom which was first experienced by the revolted angels cast out of Heaven.

They came down in spins.

Over the two years that Bunny spent taking flying lessons he alternated between suicidal despair at his incompetence and muffed landings (‘I would do well to shoot myself) and radiant feelings of exaltation, drugged with oxygen and the poetry of power and freedom.

No thrill could ever again compare in intensity.

Even the death of his close friend Garrow Tomlin, killed while practising spins in his plane, failed to dampen his enthusiasm.

For the rest of his life Bunny watched the skies from the perspective of one who has ploughed the clouds alone.

Ethel Mannin, though she never took the controls herself, was another passionate air-traveller for whom the experience reawakened earthbound sensibilities:

Nothing of the earth was visible; we were in a new world in which the sky was blue and the sun shone, and where gigantic white mountains rose up out of a billowy white sea.

It was like a child’s dream of heaven, and wanted only white-robed angels with golden harps to complete the picture… I have known few experiences as exciting or as beautiful.

A tiny minority of intrepid passengers travelled in commercial aeroplanes before the Second World War; they were noisy monsters with a roar so loud that flyers had to plug their ears with cotton-wool.

Once in the air they lurched and rolled like bobbing corks.

Every few minutes they ‘dropped’ like a lift.

Landing could be terrifying.

Ladies in fact rarely flew, and Ethel Mannin frequently found herself the only woman on board.

The Grasshoppers Come

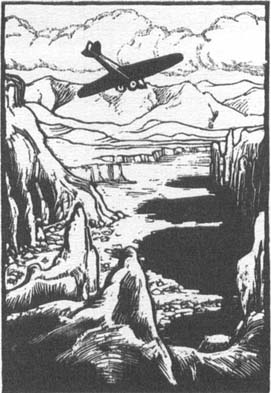

was David Garnett’s second book about flying.

His wife, Ray, illustrated it with her woodcuts.

Long distance flights happened in stages.

Ethel Mannin’s five-hour journey from Croydon to Frankfurt had two stop-offs, the first at Brussels, the next at Cologne, where she had an hour’s wait for the German plane which was to carry her on to Frankfurt.

In the aerodrome cafe the nice pilot took advantage of this opportunity to get into conversation with her.

They had lunch together and he flatteringly recognised the author of

Confessions and Impressions,

which his wife had read:

His wife would be so interested to hear that he had met me, and why had I such a down on marriage… I said because I regarded freedom as the most important privilege of the human being, and how late did he think the ‘plane would be arriving in Frankfurt.

He said about an hour, and surely I regarded love as more important than freedom…

For an hour they talked together of life and love, ‘always the most interesting conversation between a man and a woman’, until Ethel’s flight for Frankfurt was ready to take off.

She left him with regret.

*

It would be naive to wish to turn the clock back to a time when one could sit in an airport café and philosophise with the pilot.

Ethel Mannin’s travel writings can make us nostalgic for her sense of a ‘brave new world’ full of opportunities for exploration.

It is growing hard to imagine how fresh, how enchanted, how remote some of those destinations must have seemed to pioneers like her.

The dream of seeing vineyards and houses with green shutters can come true for almost anyone living in this country now.

In her biographical novel

Jigsaw

(1989) Sybille Bedford wrote:

What was it like that French Mediterranean coast between Marseilles and Toulon, Toulon and Fréjus, in the Nineteen-twenties?

Le Petit Littoral, the unfashionable part of the Côte d’Azur

(not

the Riviera) with its string of fishing ports and modest resorts – Cassis, La Ciotat, Saint-Cyr, Bandol, Sanary, Le Lavandou, Cavalaire, Saint-Tropez?

The sea and sky were clear; living was cheap; there were few motor cars,

there were few people…

Some of this changed soon.

In that very 1926 Colette discovered the aestival Midi, the clarity of the mornings, the stillness of the sun-struck monochrome noons, the magic of the scented nights.

She bought a summer house at Saint-Tropez, La Treille Muscate; clans of artists and writers followed with their entourages…

And the rest is history – a history which repeated itself across Europe, in the Balearic Islands, on the Italian Riviera, on the Costa del Sol, in Cornwall.

It has taken less than a century for villages like Puerto de Pollensa, St Tropez and St Ives to metamorphose from primitive fishing communities into coach tour destinations.

Though artists are by no means the only culprits, we must accept the paradox that many enchanted islands have been damaged by the very outpourings of those who loved them best.

Searching vainly for unspoilt territory, the artist may eventually conclude that only one realm still remains intact where the committed Bohemian traveller can retain a sense of identity.

On the road, his restless quest for truth, beauty and meaning eternally finds shape – encapsulated in the image of a solitary man walking, slowly, across a distant landscape.

9. Evenings of Friendliness

What do Bohemians want out of life? – Is a party an occasion for th

observation of the rules of Society? – How can one entertain with no

money? – Must guests know each other, or their hosts? – What kind

of behaviour is acceptable at parties? – How have pubs and

clubs changed their status? – Is it necessary to stay sober? –

Is it all worth it in the end?

What is life

for

?

Sooner or later, in one form or another, the basic question arises.

Bohemians in the early years of the twentieth century, though a tiny minority of society, seem to have been very clear about a number of things that life was

not

for.

It was not for making money, not for status, nor social advancement, nor political power.

It was not for God, not for property, not for fame.

It is easy to say, then, that such people lived for art.

But if that were all, many of their lives would be overcast with a sad sense of waste and disappointment.

So few of them were geniuses, so few of them produced work with any claim to immortality.

Who still reads Geoffrey Taylor’s poetry or Ethel Mannin’s collected journalism?

The general public are on the whole ignorant of the art of Daintrey and Kramer.

And yet evidently significant and important changes in society were generated by exactly such people, who at their best, and despite poverty and hardship, felt themselves to be heroes, on the winning side in life.

Artists fought tooth and nail for liberty on so many fronts, emotional and sexual, aesthetic, social, political.

Slowly but surely, feminism was winning ground.

A new freedom was entering the relations between the sexes.

In the upbringing of their children they espoused permissiveness; they let the light into their homes, garlic into their food, colour into their clothing.

By the twenties people like Bunny Garnett were beginning to feel that ‘the forces of intelligence and enlightenment were winning’:

I was sure that the dark ages were over; the persecutors drawn from Church and State, if they had not been routed, were being sapped from within.

The ice age of Victoria and the vulgarity of the Edwardians were over and a generation was

growing up which would enjoy – as many of us were enjoying – uninhibited freedom…

The twenties were years of joy, of freedom and of enlightenment.

It was above all in the conduct of relationships that people like Bunny experienced such release for the first time.

Social life, high days and holidays, parties and gatherings, were the heart of Bohemia, its glory, and arguably its

raison d’être.

*

Bohemia has always celebrated camaraderie.

Murger’s

Scènes de la Vie de Bohème

is full of descriptions of Latin Quarter parties, where poets and painters made merry for a few sous.

When they were in funds they ate and drank, when they were not they danced and burnt the chairs to keep warm; the fires of their friendship were quenched only by the tears of their passion.

To many English readers, this spontaneity was irresistible.

La Vie de Bohème

showed the way, and in

Bohemia in London,

Arthur Ransome describes the English equivalent.

The painter’s day ends as often as not with an impromptu gathering of artists, poets and actors at somebody’s studio.

You may have to supply your own chairs if you want to sit down.

A piano helps, or a witty model telling funny stories.

The room fills up with tobacco smoke.

There is chess, and chat, and the gathering breaks up late.

Another night Ransome finds himself at Gypsy’s place in Chelsea.

The guests are picture dealers and artists, models and actors.

They clamour for Gypsy to sing them a song, but first she offers them drinks:

‘Who is for opal hush?’ she cried, and all, except the American girl and the picture dealer, who preferred whisky, declared their throats were dry for nothing else.

Wondering what the strange-named drink might be, I too asked for opal hush, and she read the puzzlement in my face.

‘You make it like this,’ she said, and squirted lemonade from a syphon into a glass of red claret, so that a beautiful amethystine foam rose shimmering to the brim.

‘The Irish poets over in Dublin called it so…’ It was very good, and as I drank I thought of those Irish poets, whose verses had meant much to me, and sipped the stuff with reverence as if it had been nectar from Olympus.

Enthroned in a chair covered with gold and purple embroidery, Gypsy tells Caribbean folk tales in the old Jamaican dialect which she had learnt at her nurse’s knee.

She sings, and recites Yeats’s poetry.

Then a beautiful Scottish

girl performs sea shanties while incense rises over the piano and perfumes the room; Ransome feels he has returned to the days of the troubadours.

This was ‘my first evening of friendliness in Chelsea’; there were to be many more.

Ransome luxuriated in those companionable hours spent talking, drinking and smoking.

For him, to be among compatible, spontaneous, tolerant, informal friends was simple heaven.

Those qualities gave a certain coherence to the ramshackle, amorphous network of Bohemian life.

Money, status and material things were blissfully irrelevant if the atmosphere was one of trust, if one shared a common aim of enjoyment, and a mutually serious concern – the pursuit of art.

Yet ‘evenings of friendliness’ are by their nature ephemeral.

How can one recapture the laughter, the talk, the glances, the heat and hubbub of an evening in the Cafe Royal in 1905, or a binge at Mallord Street in 1915?

How can one bring back the atmosphere of a ‘studio rag’ in St John’s Wood in the twenties, recapture the beery disreputableness of the Fitzroy Tavern, or invoke the guttering clientele of the Gargoyle Club in the thirties?

*

It is hard to characterise the flickering, fitful social scene that was Bohemia during those decades, without briefly recalling the sombre backdrop against which it was played out.

For decades the upper and middle classes had held a tyrannous stranglehold over the conduct of everyday social life in this country.

Those twin pillars of the social edifice, status and advancement, dominated the architecture of nineteenth-century social life.

They were designed to ensure that whims and idiosyncrasies were limited within the walls of respectability and propriety.