An Accidental Tragedy (2 page)

Read An Accidental Tragedy Online

Authors: Roderick Graham

I have kept the modernisation of spelling and grammar to the minimum required for clarity and have dated the turning of the year at 1 January. There were three principal currencies in use during Mary’s lifetime – Scottish merks, crowns and pounds; English pounds, shillings and pence (£, s, d) and French livres tournois and crowns – and, unfortunately, there is no convenient factor by which we can multiply sums to convert to modern values. However, by the end of the sixteenth century an English professional – teacher, shopkeeper, or parson – could live comfortably on £20 annually (£90 Scots, 160 livres, 100 French crowns).

Since weaponry was an integral part of male life, some explanations may be necessary. All males carried a dagger, which in Scots was called a ‘whinger’, and occasionally a long sword or rapier. In battle, swords were either of the rapier variety or the basket-hilted broadsword. The claymore was a two-handed sword used best on horseback. The 12-foot-long Scottish pike was used in a phalanx or ‘schiltron’ formation to repel cavalry. Firearms were, apart from cannon, relative newcomers and were mainly an early form of musket called variously ‘arquebus’, harquebus’, ‘hagbut’ or ‘hackbut’. To avoid unnecessary confusion I have called them arquebus throughout.

Acknowledgements

Above all I must thank my publisher, Hugh Andrew, who suggested to me that he felt the time to be ripe for a balanced biography of Mary Stewart. Without his initial support, this book would never have been written. A place beside Hugh Andrew must be given to my wife, Fiona, for listening, with every sign of cheerful interest, to two years’ worth of often repetitious conversation about Mary. Fiona then took on the task of initial copy-editing, brushing aside my irritation when she pointed out, for example, that Mary was unlikely to have been crowned on two different dates. It was a labour of Hercules, carried out smilingly, and I thank her for it.

Andrew Simmons, as managing editor at Birlinn, gave help and encouragement in huge quantities, along with the most tactful of suggestions, while providing eagle-eyed editors to clarify my sometimes presumptuous narrative. Laura Esslemont and Peter Burns ransacked picture libraries to make a pleasure out of a chore.

Dr Jenny Wormald of St Hilda’s College, Oxford and the University of Edinburgh, read the manuscript and made extremely helpful suggestions. Michael Lynch, Professor Emeritus of Scottish History at the University of Edinburgh, read the manuscript for historical veracity and gracefully suggested corrections. Owen Dudley Edwards, formerly Reader in History at the University of Edinburgh, gave invaluable information on the various canonisation campaigns with breathless enthusiasm.

Technical help from the Royal Armouries at Leeds on Henri II’s fatal joust and a weather report for the night of Darnley’s murder from the Nautical Almanac Office filled in two vital blanks.

Medical advice from Professor I.M.L. Donaldson, Dr Morrice McCrae and Dr Peter Bloomfield helped with diagnoses made at a distance of 500 years. Kenneth Dunn, Senior Curator of Manuscripts at the National Library of Scotland, corrected my attempts at Latin translations, and the issue staff, both there and at the library of the University of Edinburgh, found books and manuscripts with their customary skill and helpfulness.

However, none of these people can be held responsible for the way in which their advice and information have been presented and any errors are mine.

Family Trees

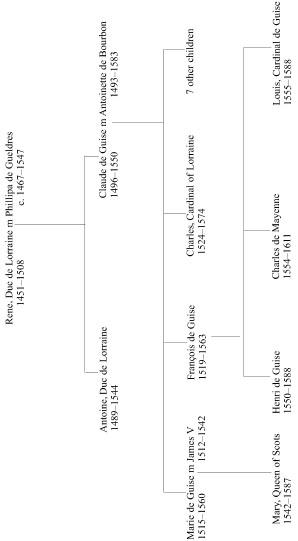

Guise

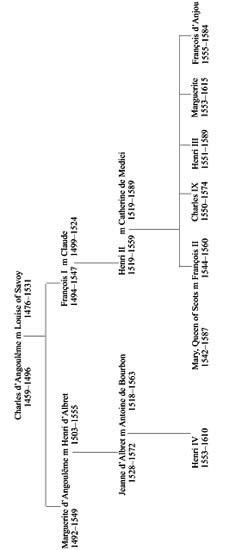

Valois

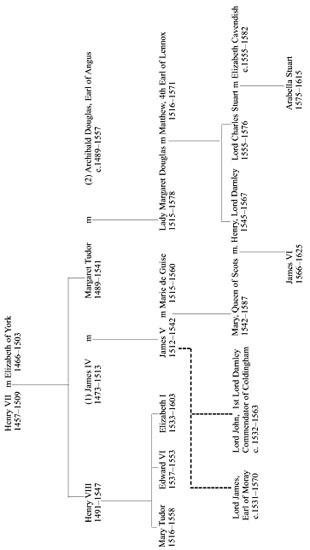

Tudors/Stewarts

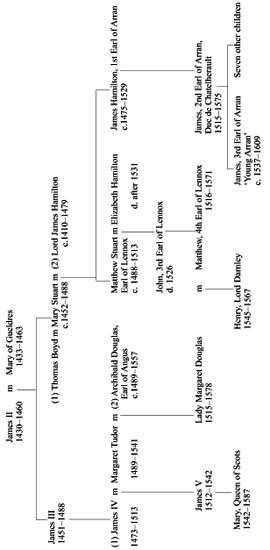

Lennox/Arran

PART I

Scotland 1542–48

CHAPTER ONE

As goodly a child as I have seen

Early in the morning of 8 December 1542 armed messengers left the warmth of the Linlithgow Palace guardrooms at the gallop, their breath steaming in the sudden chill and their horses’ hooves striking sparks from the frozen cobbles outside the forecourt. Behind them the new white walls of the south façade gleamed in a reflection of the snow-covered ground. After only a few yards they passed the church of St Michael before plunging down the steep hill into the town, where they took their separate icy roads. Heavy snowfalls had blanketed the country in one of the worst winters of the century. The horsemen were all carrying the urgent news that Marie de Guise, Queen of Scotland, was safely delivered of a child. As her previous two children had died, more than usual care had been taken over the birth of this child in a first-floor room in the palace, and the messengers had been standing by since her labour had begun.

Of these messengers, by far the most important was the man heading for the royal hunting lodge of Falkland Palace, where James V was lying, gravely ill. With little daylight and only one prearranged horse stage, the messenger would lodge for the night twenty miles distant at Stirling before turning east across Fife. His package was heavily sealed, secured in a saddlebag, and he did not know its precise contents, although the rumours in the guardrooms had all been of the queen’s successful confinement. Since he had been given two loaded pistols as well as his broadsword and dagger, he knew it was a vital despatch and that, given the rumoured condition of the king’s health, speed was of the utmost importance.

In Stirling, he slept in his clothes with his sword by his side and a pistol on top of his package under his pillow. Early next day he left Stirling while it was still dark to cover the thirty-five miles to Falkland Palace, where he finally delivered his despatch. It was immediately unsealed by a courtier, who read the document, frowned, and took the news to King James, now lying in his bed in his sickroom. At first the news was good in that the queen had survived childbirth and was safely delivered of a healthy child. The bad news which followed was that the child was a girl, to be called Mary. It was her mother’s name, and 8 December was also the feast of the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin. It is possible that Mary was actually born the day before and the record was subsequently changed to allow what would be seen as a happy coincidence of dates.

James V had not been with his queen, but since royal fathers were seldom present at their wives’ confinements, this was not unusual. What was unusual was that, a few days earlier, James had been personally leading a raiding force of 18,000 Scotsmen in a crossing of the English border at the Solway Firth. To invade Henry VIII’s England at this time was like poking a stick at a very angry bear, and James knew it.

On the expedition, James had set up his headquarters twenty miles north of the border at Lochmaben, and the raiding party set out under the command of Oliver Sinclair, James’s loathed favourite, to cross the River Esk. Raiding parties were not unusual in the Border area, where a precise delineation of the frontier was impossible to achieve, and widespread cattle and sheep stealing, combined with kidnap and extortion, were carried out under patriotic banners. The area was generally known as the ‘Debatable Lands’ and even today, for imaginative tourists, its undoubted beauty is tinged with the feeling that hostile horsemen may be lying in wait just over the next hill.

The raiders entered England and burnt property belonging to the Grahams, but achieved nothing except to warn the English that a Scots army was nearby. The English deputy warden of the West March caught up with the Scots who were re-crossing the

River Esk on their way home. With ‘spears of the borders to prick at them [he] set upon their hinder ends and struck down many’. The Scots were then trapped by the rapidly rising tide in the Solway Estuary and the retreat turned into a total shambles. The incoming tide drowned many, while others were trapped in the marshes of Solway Moss or simply surrendered to whoever they could find to prevent their certain slaughter. One sorry remnant was overtaken in Liddesdale and sent home barefoot, clad only in their shirts. In the bitter November weather few survived. The English pursuit continued until 12 December, being now justified as retribution for a cattle raid. Their haul, apart from prisoners, amounted to 1,018 cattle, 4,240 sheep and 400 horses.

It was when James realised the extent of the losses that he fell into a deep depression and turned north, accompanied by only his personal retinue. There are reports that he first travelled to Tantallon Castle on the south-eastern coast of the River Forth to say farewell to his mistress, who was being cared for by the wife of Oliver Sinclair, but he certainly rode to Edinburgh and put some of his personal affairs in order before visiting his wife, Marie, awaiting the birth in Linlithgow.