An Evening with Johnners (4 page)

Read An Evening with Johnners Online

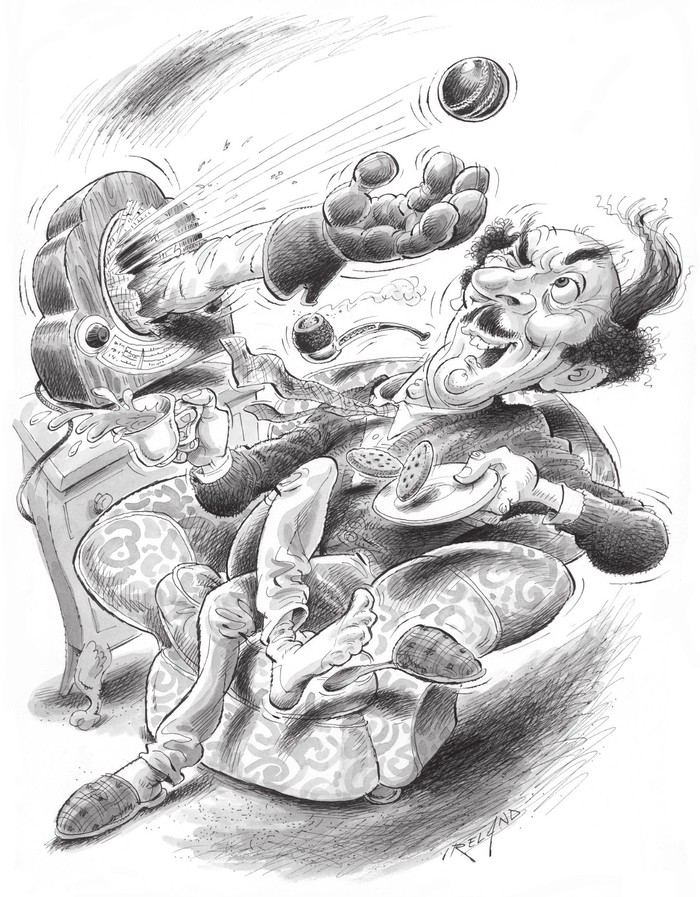

Authors: Brian Johnston

I

remember my first broadcast. I’d only been there about a fortnight when they discovered an unexploded bomb in the lake in St James’s Park. They drained the lake and there was this huge great sausage of a German bomb and it was announced they were going to blow it up at eleven o’clock one morning and my boss said, ‘Right! You can do your first broadcast. You go down there. We’ll

interrupt the news and you can describe the blowing up of the bomb.’

So we went down with the engineers and we were standing on a little bridge when a policeman came up and said, ‘What are you doing?’

I said, ‘We’re going to commentate on the blowing up of the bomb.’

‘Not here, you’re not,’ he said, ‘it’s far too dangerous. Go in there.’ And he pointed to the ladies’ loo.

So I went in and stood up on the seat and looked through the louvred windows and I did the commentary from there. I always say I came out looking a bit flushed!

At that time I didn’t have anything to do with cricket at all. But I was so happy, because I loved the theatre and my job was to do radio broadcasts live from musicals like

South Pacific, Annie Get Your Gun, Oklahoma

and

Carousel.

I used to commentate from a box and describe anything visual on stage which the listener might not understand. So I got to know all the stars of all the musicals.

Then every Tuesday we used to go to a music hall

[Round the Halls]

and broadcast three acts live from there, and I got to know all the variety artists such as Arthur Askey, Tommy Trinder and Jimmy Edwards. So I was absolutely in my seventh heaven.

I

t wasn’t until March, two months later, when the telephone rang and a friend of mine called Ian Orr-Ewing, with whom I had played cricket before the war, rang up and said, ‘Help! I am just out of the Royal Air Force, I’m now in charge of sport on television, we’ve got two Test matches this summer against the Indians, at Lord’s and The Oval, and we’ve got no commentator. I know you can play. I know you can talk a bit. Would you like to be the commentator?’

So, on that little bit of luck, for the next twenty-four years I did all the Test matches on television in this country. After that they got browned off with all my jokes so they sacked me and I went straight across to radio and I’ve been on

Test Match Special

for another twenty-four years. Just on that one telephone call.

I

did a lot of television and radio in those days and people often say, ‘Which is the easier of the two?’ Candidly, radio is by far the easier, as long as you’ve got the gift of the gab, powers of description, moderately good

English and a reasonable voice. You can be yourself but you have to be the eyes of anybody sitting in an armchair at home or in their car, of blind people, or of someone listening on the beach. You’ve got to paint a picture for them and tell them all you can see, so that they can imagine what it is like.

That’s the job of a radio commentator but, of course, on television the camera shows all that, so you’ve merely got to dot the i’s and cross the t’s and explain perhaps who someone is if they might not recognise them. You have to edit yourself before you say anything. You think, ‘Shall I speak or shan’t I?’ and to me that is unnatural. We used to have a golden rule which went, ‘Only speak when you can add to the picture’ and I learnt that the hard way.

I

n 1954 the Queen and Prince Philip went on a tour of Australia and when they came back the BBC decided to televise their return. They were going to go up as far as the Tower Bridge in the Royal Yacht

Britannia

, get into a launch and travel up to Westminster Pier where they would come ashore and go back to Buckingham Palace in the Irish State Coach.

Before these sorts of events you always talk over with your fellow commentator who’s going to say what.

Richard Dimbleby was going to be on Westminster Pier, so it was decided that he was going to talk about the people waiting to greet the Queen: the Queen Mother, Princess Margaret, the Lord Lieutenant, the corgis and so on, and he would describe her coming ashore.

But when she got into the Irish State Coach he would pass over to me halfway down Whitehall, where I would be waiting. I would explain about the Irish State Coach and the Escort, the names of the horses and that sort of thing.

So came the great day and I heard Richard in my headphones just as we’d planned. But as he was beginning to get to the end of his preparation, he looked up the river and said, ‘I can’t see the Queen arriving yet, it’s a bit misty up there. Still, perhaps as we’re waiting, I’ll tell you something about the Irish State Coach. It weighs thirteen tons, it was given to Queen Victoria, it’s made of gold and it is used on state occasions.’

So I was crossing out my notes, as I was listening. Then he said, ‘The Queen still isn’t here but you might be interested to know the names of the horses. The front one is called Monty, the second one Eisenhower, and they were given to the Queen by Queen Wilhelmina. Well, it must be the mist up there … but anyhow, the Escort today are the Blues in front, commanded by Lieutenant Harcourt-Smith and in the rear are the Life Guards with their white plumes and red tunics …’ and so on.

I was going mad, crossing things off on my bits of paper. Then he said, ‘Ah, here she comes!’ and he did all that he was meant to do, and described her coming ashore and the people being presented.

When she got into the coach he said, ‘Over to Brian Johnston halfway down Whitehall,’ and do you know, the next day people said to me, ‘You did the best television commentary I’ve ever heard. Better than Richard Dimbleby.’

I realised why because, when they came past me, I watched in silence on my monitors as they went into Trafalgar Square, turned left under Admiralty Arch and went about two hundred and fifty yards up the Mall. As they approached Buckingham Palace I said, ‘Over now to Berkeley Smith at Buckingham Palace.’

That’s all I said! But what else could I say? They knew the Queen, they knew Prince Philip, they knew the horses and the Escort and they knew all about the Irish State Coach. So that was a lesson which I don’t think many people follow nowadays, and perhaps they talk too much.

A

nd I learnt another thing from that television time. In 1952 I was chosen to be one of the commentators for the King’s funeral, which wasn’t quite my cup of tea. I thought, Look, you can’t get out of it with a joke if you

make a mess of things. You must get off to a good start. So for the first, and the last, time in my life I decided to write out my opening.

I found out that the procession was going to be led by five Metropolitan Policemen mounted on white horses, so I wrote it down. We had about a week before the funeral and I learnt it every night before I went to sleep.

On the day, Richard Dimbleby was in St James’s Street. He described the procession coming past and as it wended its way up Piccadilly and was approaching Hyde Park Corner he said, ‘Over now to Brian Johnston at Hyde Park Corner.’

My television producer in my headphones said, ‘Go ahead, Brian. Good luck,’ and I said, ‘Yes, here comes the procession now, led by five Metropolitan Policemen mounted …’ and on the word ‘mounted’ I luckily looked up and they

weren’t

on white horses.

It was no good pretending they were because at least there was black and white television in those days, even if not colour. So very lamely I said, ‘Here they are … mounted on horseback.’

My producer, and remember this was a serious occasion, shouted in my ear, ‘What on earth do you think they are mounted on? Camels?’