An Intimate Life (16 page)

Authors: Cheryl T. Cohen-Greene

Intense pain radiated from the top of my neck to below my shoulder blades. It kept me from standing up straight. The pickup truck had crashed into us, making our van summersault across the median, into the southbound lane. All four tires were blown and the rubber splayed out in black, jagged tongues. I heard sirens getting louder. Did this mean they were getting closer?

At the hospital they took X-rays of my back and found that I had three compression fractures between my shoulder blades and damage to the base of my neck. I realized later that Jessica had been protected by the truckload of stuffed animals we had packed for her. The impact tossed her around like a rag doll, but, fortunately, she careened from stuffed giraffe, to stuffed pig, to stuffed elephant. I was told that Eric was okay, but when he was around four he was treated for a neck problem that I attributed to the car wreck. Michael wore his seat belt and escaped with only a bruise on his foot. The doctor wrote me a prescription for Darvon and told me to take the next appointment I could find with an orthopedist.

Since our camper was totaled, Bobby, one of our friends in San Francisco, drove down to Hollister to pick us up. The five of us climbed into his van. Jessica sat on Michael’s lap and Eric was in my arms for the two-and-a-half-hour trip north. Even the slightest bump or start made my neck scream, so I popped another Darvon. In retrospect, it seems like I should have asked the doctors if it was safe to keep nursing Eric while I took pain medication. Luckily it turned out that it was, but I didn’t ask because at the time I assumed doctors were all-knowing and infallible.

We arrived at Bobby and Peggy’s around 7:00 PM and I hobbled to bed. As I lay there staring up, the back of my head pressed flat against the mattress and the pillow flung to the floor, I worried about the toll my injuries might take on my sex life. What if I was hurt so badly that sex would be too painful, or what if I was no longer able to move enough to have it? I shook Michael awake.

“Huh . . . what . . . are you okay?” he said.

“I’m scared. I’m scared I won’t be able to have sex again. So, let’s try. Let’s please try.”

“Now? I thought you could barely move.”

I turned over onto my side. A bolt of pain shot down my neck and into my back. I bit my cheek to keep from screaming.

“Okay, get behind me and, please, let’s do it,” I gasped.

Michael wedged himself up against me.

“Ow, oooh, ow,” I whispered and my eyes misted.

“Are you okay?” Michael asked.

“Yes. Okay.”

I turned my hips and lifted my leg a little so he could slide his penis into me.

“I’m afraid this will be the last time,” I said.

“This isn’t going to be the last time, Cheryl.”

“I know, but if it is . . . ”

“Cheryl, it’s not the last time.”

The next day I could barely move and Michael had to help me stand. Peggy found an orthopedist at a nearby hospital who could see me that day. Michael slipped a muumuu-style dress over my head and helped me to the car.

The orthopedist informed me that I had fractures in three of my vertebrae and a break at the base of my neck where it met my shoulders. Luckily, my spinal cord wasn’t damaged. I felt so fortunate at that moment even though I would need to be in a brace for six months. The doctor disappeared for a few minutes and when he came back he held something that looked like a cross between a corset and a straightjacket. It was made of canvas and had rods that held it straight in the back. It closed in the front with Velcro-covered straps and was crisscrossed in the back with strings to tighten it. Normally, it would have covered my breasts and gone down to the base of my spine, but because I was still nursing Eric I couldn’t have my breasts covered. The doctor fitted it just below them. I gasped in pain as he pulled the strings to tighten it to my body.

Despite our inauspicious start, we did our best to get settled in the Bay Area. Michael began house-hunting and soon rented a bungalow across the bay in Berkeley. Julius sent us money, again. We still had several hundred dollars left from our original thousand and we used it to buy a 1954 Cadillac Coupe de Ville. Because it was yellow on the bottom and black on top, we dubbed it “the yellow submarine.” After the accident, I wasn’t taking any chances. The car may have been out of style, but it was safe. I felt like I was driving a moveable bunker and that’s exactly what I wanted.

Michael was floundering and I was in no shape to hold a job, so we went on welfare. Between it and an occasional cash infusion from Julius and Sadie, we scraped by month to month. Our new home was across the street from an elementary school and I enrolled Jessica in kindergarten. I furnished our house mostly with Goodwill buys, reconnected with some other friends who had also gone west, and did my best to keep my spirits up.

The accident was terrifying and traumatic, but it eventually led me in one positive direction. As 1970 rolled around, I started to slowly recover my strength and mobility. I took yoga classes and did other exercises, but I was still inactive compared to my pre-accident days. I put on weight. Since my teenage years I’d always thought I was too fat, and it only got worse after the accident. This was the Twiggy era and curves had gone the way of car fins. I had never been clinically overweight, but as I was forced into a more sedentary lifestyle I felt out of shape. My new, fuller figure aggravated my body image issues and sometimes sent me into bouts of panic.

Every afternoon I waited on our front steps for Jessica to come home from school. She would come out in mid-afternoon, wave to me from across the street, and look both ways with her teacher and classmates. When it was clear to cross, she ran toward me with her arms flung out. It was the best time of my day, and it wasn’t unusual for me to go out earlier than necessary to wait for her.

My schedule coincided with a neighbor’s. She was a thickset woman with a heavy blonde braid that hung down to her waist. She’d always come by on her bike as I settled down on the steps with a book. As she cycled, her wide thighs pumped up and down and her large breasts jiggled, seemingly unrestrained by a bra. The rack on her bike was crammed with paintbrushes, colored pencils, and other art supplies, so I figured she was a student at the nearby art college. She looked to be around my age and we often smiled at each other.

One day as she pedaled slowly down the street I waved and said hello. She stopped and we started to chat.

“Are you an artist?” I asked.

“I’m taking classes at the art school and I also do some modeling,” she said.

Modeling? The only models I’d seen were the wispy creatures who wore haute couture and haunted the pages of fashion magazines, the ones I wanted to look like.

This savvy, self-confident woman must have sensed my doubt. I hoped I hadn’t offended her.

“I do nude modeling for the painting and sculpture students, and I’m more in demand than skinny women. They love all my curves and creases,” she answered.

Suddenly I saw an opportunity. If she could model, so could I. I could earn some extra money and maybe even start to feel better about my body.

“How’d you get involved in that?” I asked.

“Oh, the school always needs models. It’s a great way to earn some money, especially if you don’t want a straight job.”

I summoned up my courage and asked, “Do you think I could do it?”

“Sure. They’d be happy to have you.” With a cobalt blue pencil she scrawled a phone number on the corner of a piece of drawing paper, tore it off, and handed it to me.

Within a year I was modeling regularly for students at local art schools and for a few full-fledged artists. I began to develop first an acceptance and then an appreciation of my body. Occasionally I saw flashes of excitement on the artists’ faces, which surprised and delighted me. My body hadn’t changed, but my perception of it sure was shifting. When I looked at their paintings and sketches of me, I saw them through the artists’ eyes. The bulges that I thought were so awful actually began to look appealing.

Holding poses for lengthy periods also gave me plenty of time to think, and I started to reflect on the fluid nature of beauty. It was hard not to. I was coming to peace with a body that I had thought of as a misfortune for a long time.

For the first time in my young life, I started to think about how the notion of beauty isn’t fixed, and how impossibly slippery the idea of the perfect body is. In those days, the waif was the ideal. A couple of decades earlier Marilyn Monroe could lay claim to the perfect figure. I did a little research and discovered Lillian Russell, a sex symbol in the late 1800s, who, at times, tipped the scale at two hundred pounds.

It was the beginning of a process of freeing myself from unrealistic, highly manufactured standards of beauty and perfection. Slowly, I started to realize that a perfect body probably can’t be reliably defined, and even if it could, I didn’t need perfection to feel good about the body that carried me through life.

I could not have known it then, but several years later this process would help me when I worked with one of the few women clients in my surrogacy career.

FIVE GENERATIONS. CLOCKWISE: My father, his mom (my Nanna Fournier), her Mom, (my Great Grandmother) and her Mom, (my Great, Great Grandmother) holding me in late 1944.

My Mother at 19 in December 1943.

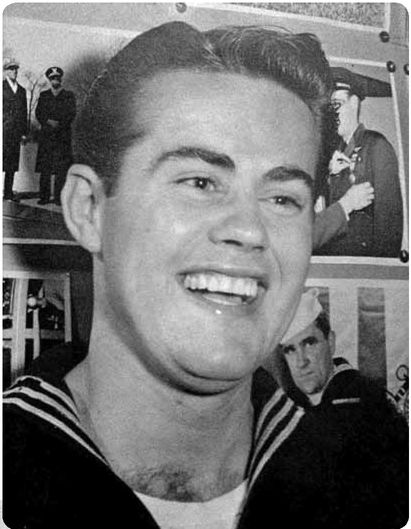

My Dad at 22 in 1943.

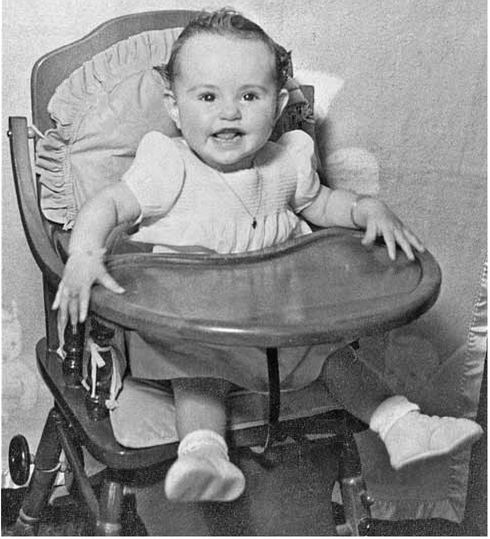

Me at 8 months in 1945.