An Intimate Life (19 page)

Authors: Cheryl T. Cohen-Greene

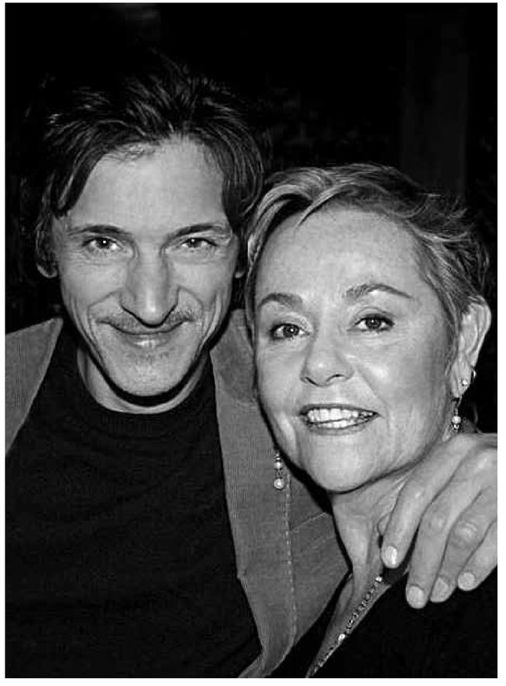

John Hawkes and me on June 8, 2011.

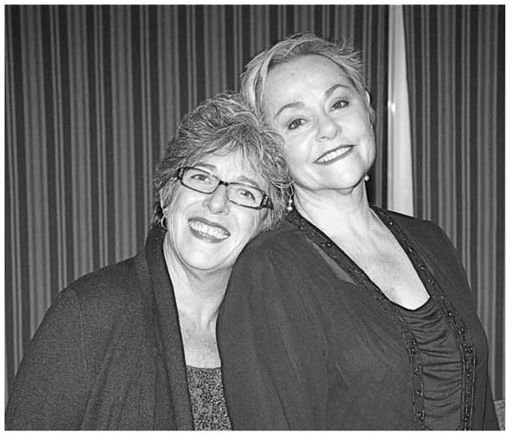

My Cousin Susan and me before the party following the premiere of “The Surrogate” on January 23, 2012 at the Sundance Film Festival in Utah.

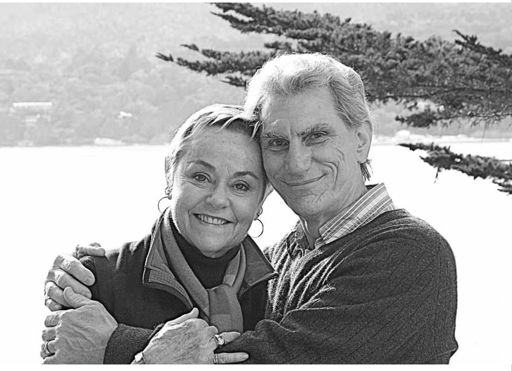

Bob and I at our annual family Oyster Fest at Tomales Bay, October 2011.

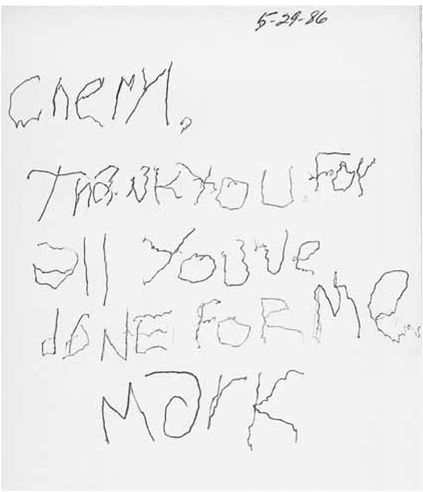

Mark O’Brien wrote me this card after our last session.

Mark O’Brien sent me this Christmas card in 1998. He died on July 4, 1999 from post-polio syndrome.

My friend and confidant for nearly half a century, Marshasue Cohen in 2004.

9.

past perfect: mary ann

A

s far as I could tell, Mary Ann’s body was nearly perfect. She had long legs, a slim waist, and a stomach as flat as a baking sheet. Only her breasts, which were too big for her lithe frame, looked off and that was because they had been surgically enlarged. Jodie, Mary Ann’s therapist, had described her as a stunning woman with body image issues, and when she walked into my office for our first session in 1988 that first part was obvious.

Up to this time I had only seen a few women clients. Most heterosexual women who seek the services of surrogates are referred to males, since so much of the work is about modeling a healthy sexual partnership. Mary Ann’s difficulty in the bedroom sprung solely from a body image issue that her therapist believed I could help her address. As a surrogate, I looked forward to the challenge of working with a woman who struggled with an issue that affects so many of us. It would be a different dynamic and I would have to tailor the protocol to her needs, but I had a definite sense that I could help my new client.

When Jodie described Mary Ann to me, it seemed as though she were talking about a younger version of myself. Here was a woman who was both deeply insecure and profoundly uniformed about her body. I often thought about how much I would have benefited from the solid, nonjudgmental advice I hoped to share with Mary Ann.

At our first appointment, Mary Ann sat across from me on my office sofa. We chatted for a few moments before I brought up the concern that had brought her to see me.

“As you know, Jodie gave me some background on the issue that brings you here today. Can we start by talking a little about it?” I said.

“Okay,” Mary Ann said.

I paused for a few seconds to see if she would continue. When she didn’t I said, “Body image issues are very common, especially in women. I struggled with them for a long time.”

“I’m not sure if it’s a body image issue or if there is something really wrong with me.”

“I understand from Jodie that you’ve been examined by your doctor and he doesn’t see any abnormalities, so I think we can assume that this is a perception issue, rather than a medical one.”

“So, you think it’s normal.”

“Do I think what’s normal?”

“Having a vagina that’s uneven.”

I wasn’t surprised to hear that this was at the root of her struggles. I could only assume she’d never seen another woman’s labia. I did, however, want to understand why she assumed hers were abnormal. “Yes,” I started, “but what you’re talking about is not your vagina. It’s your labia, and many women’s are uneven.”

Much of my work with Mary Ann would center on education, starting with anatomy. I explained to her that the vagina is internal and can only be seen with a speculum. The vulva, which includes the clitoral hood, clitoris, vestibule, labia minora, and labia majora, is the external part of the female genitalia.

Mary Ann was worried because the left side of her inner labia was longer than the right—or at least that is what she believed. She had never actually looked closely at her vulva, but when she felt it she could discern an asymmetry.

I planned to walk Mary Ann through a couple of exercises and show her some educational materials, but first I wanted to understand why she was so troubled by what she perceived as an imperfection. What did it really mean to her that her vulva was not “perfect?”

When I asked her about this she said it made her feel like she was secretly ugly to her husband and that it ate into her self-esteem to be anything short of physically flawless. Mary Ann prided herself on maintaining a beautiful body. At thirty-eight she had never had children. Regular tennis matches and Jazzercise had toned her muscles and sculpted the delicate curves in her five-foot, eight-inch frame. She obviously pegged a lot of her self-worth on what she looked like and I hoped that our work together would help to change that.

Surrogacy work takes many forms. It always includes a mix of education, exploration, and sexual play, but the balance between them shifts according to the client and his or her needs. For Mary Ann, my task would be to help her better understand that bodies—including vulvas—come in all different shapes and sizes, and that she was not at all abnormal or freakish. I wanted her to see that she comfortably fit into the spectrum of body types and to change her belief about being far outside of what was normal. I also hoped that I could help her dispense with Madison Avenue–generated standards of perfection, but that was, strictly speaking, beyond the scope of our work together.

Joania Blank’s

Femalia

is a book that I often turn to in my work. It is a remarkable collection of color photographs that show the vulvas of thirty-two women. The differences between each one can be startling at first sight. Some of the models’ vulvas are pink; others are brownish. Some labia are long, some are short; some are even and some are uneven.

I slid the volume off of my bookshelf and sat next to Mary Ann on the couch.

“Ready?” I asked.

I cracked it open and slowly we went through the thirty-two pictures.

“Wow,” Mary Ann said as we thumbed through the pages. She asked me to hold on before passing over one photo of a woman whose inner labia hung down beyond the outer lips in two lush crescents.

“I never thought they could be that long,” Mary Ann said.

We flipped through a few more photographs until we came to one that showed a woman with inner labia that hung about an inch longer on the right side than on the left.

“Is that normal—really?” Mary Ann asked.

“Absolutely. Lots of women have asymmetrical labia. It’s just one of the many natural variants of female genitalia,” I assured her.

“Really?”

“Really, and remember this is just a very small group of women. It doesn’t represent all of the variety that’s out there. It’s no more unusual than having one foot that’s slightly larger than the other. You probably wouldn’t feel bad if that were the case, right?”

Mary Ann paused and looked down.

“No, but I thought that maybe I had damaged my vagi—vulva by masturbating.”

“You haven’t. I can assure you of that. It’s just your unique shape and our goal is to help you become a little more comfortable with it.”

She touched the photo with her fingertip as if to reassure herself of what she was really seeing.

We paged through the rest of

Femalia

. Even though I had gone through it countless times I was moved, as I often am, by the beauty and diversity of women’s vulvas. For Mary Ann it was the first time she’d seen a nonclinical, real-life representation of female genitalia and it was as eye-opening for her as it is for most of us. I hoped she was beginning to question the standard of perfection that she had fixed in her mind and that the range of normal was widening for her.

As we looked at the last of the women profiled in

Femalia

, I asked Mary Ann if she wanted to take a second look at any of the photos. She asked to go back to the woman whose labia hung unevenly.

“I just can’t believe it. I wonder if mine is this uneven,” she said.

“We can find out,” I said.

I explained the mirror exercise. In this case, I suggested we both participate, and that each of us closely examine each body part, from head to toe, and share our thoughts and feelings. I would go first and then it would be Mary Ann’s turn.

This exercise is valuable for a number of reasons. It offers clients an opportunity to really examine and think about their bodies. For some, it marks the first time they have ever carefully looked at their whole body. So many of our ideas about our bodies come from unreliable sources. If we’ve been told that certain areas are bad or ugly or too big or too small, we can believe that without ever really looking to see if the physical reality aligns with our opinion. This exercise offers clients a chance to start formulating their own understanding of their bodies and to compare their beliefs to what they see in front of them. Each client gets something different from this exercise. I thought it would be particularly important for Mary Ann to try to take a dispassionate look at her body, especially after viewing the eye-opening photographs in

Femalia

.