Arabian Sands (11 page)

Authors: Wilfred Thesiger

A few days later we passed some tracks. I was not even certain that they were made by camels, for they were much blurred by the wind. Sultan turned to a grey-bearded man who was noted as a tracker and asked him whose tracks these were, and the man turned aside and followed them for a short distance. He then jumped off his camel, looked at the tracks where

they crossed some hard ground, broke some camel-droppings between his fingers and rode back to join us. Sultan asked, ‘Who were they?’ and the man answered, ‘They were Awamir. There are six of them. They have raided the Junuba on the southern coast and taken three of their camels. They ‘have come here from Sahma and watered at Mughshin. They passed here ten days ago.’ We had seen no Arabs for seventeen days and we saw none for a further twenty-seven. On our return we met some Bait Kathir near Jabal Qarra and, when we exchanged our news, they told us that six Awamir had raided the Januba, killed three of them, and taken three of their camels. The only thing we did not already know was that they had killed anyone.

Here every man knew the individual tracks of his own camels, and some of them could remember the tracks of nearly every camel they had seen. They could tell at a glance from the depth of the footprints whether a camel was ridden or free, and whether it was in calf. By studying strange tracks they could tell the area from which the camel came. Camels from the Sands, for instance, have soft soles to their feet, marked with tattered strips of loose skin, whereas if they come from the gravel plains their feet are polished smooth. Bedu could tell the tribe to which a camel belonged, for the different tribes have different breeds of camel, all of which can be distinguished by their tracks. From looking at their droppings they could often deduce where a camel had been grazing, and they could certainly tell when it had last been watered, and from their knowledge of the country they could probably tell where. Bedu are always well informed about the politics of the desert. They know the alliances and enmities of the tribes and can guess which tribes would raid each other. No Bedu will ever miss a chance of exchanging news with anyone he meets, and he will ride far out of his way to get fresh news.

As a result of this journey I found that the country round Mughshin was suffering from many years of drought. If there had been grazing we would have found Arabs with their herds, but we had just travelled for forty-four days without seeing anyone. I asked my companions about floods and they told me that no water had reached Mughshin from the Qarra mountains

since the great floods twenty-five years before. It was obviously not an ‘outbreak centre’ for desert locusts. I now decided to travel westwards to the Hadhramaut along the southern edge of the Sands,

1

where I would be able to find out if floods ever reached these sands from the high Mahra mountains along the coast. No European had yet travelled in the country between Dhaufar and the Hadhramaut.

I had met with one of the Rashid sheikhs, called Musallim bin al Kamam, on my way to Mughshin, and had taken an immediate liking to him. I had asked him to meet me with some of his tribe in Salala in January, and to go with me to the Hadhramaut. I found bin al Kamam and some thirty Rashid waiting for me when I arrived in Salala on 7 January. I decided to keep Sultan and Musallim bin Tafl with me from the Bait Kathir and agreed to pay for fifteen Rashid, but bin al Kamam said that thirty men would come with us and share this pay. He explained that the country through which we should pass was frequently raided by the Yemen tribes. He had news that more than two hundred Dahm were even then raiding the Manahil on the steppes to the east of the Hadhramaut.

The Rashid were kinsmen and allies of the Bait Kathir, both tribes belonging to the Al Kathir. They were dressed in long Arab shirts and head-cloths which had been dyed a soft russet-brown with the juice of a desert shrub. They wore their clothes with distinction, even when they were in rags. They were small den men, alert and watchful. Their bodies were lean and hard, trained to incredible endurance. Looking at them, I realized that they were very much alive, tense with nervous energy, vigorously controlled. They had been bred from the purest race in the world, and lived under conditions where only the hardiest and best could possibly survive. They were as fine-drawn and highly-strung as thoroughbreds. Beside them the Bait Kathir seemed uncouth and assertive, lacking the final polish of the inner desert.

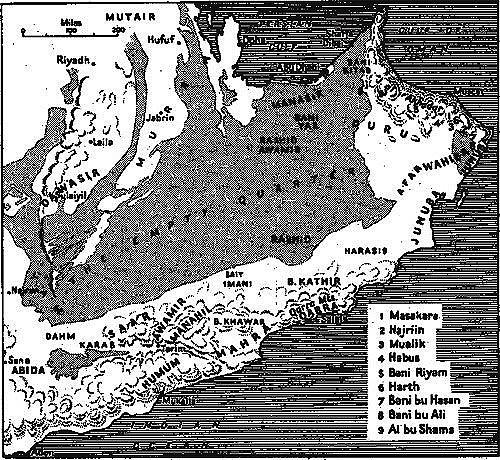

The Rashid and the Awamir were the tribes in southern Arabia who had adapted themselves to life in the Sands. Some of their sections lived in the central sands, the only place in the Empty Quarter with wells; others had moved right across

the Sands to the Trucial Coast. The homelands of both the Rashid and the Awamir were on the steppes to the north-east and to the north of the Hadhramaut. The Bait Imani section of the Rashid still lived there, and we should pass through their territory on our way to the Hadhramaut. The Manahil lived farther to the west, between there and the Awamir. Beyond the Awamir were the Saar, bitter enemies of the Rashid. The Mahra, divided into many sections, lived in the mountains and on the plateau along the coast; beyond them were the Humum to the north of Mukalla.

The Bedu tribes of southern Arabia were insignificant in numbers compared with those of central and northern Arabia, where the tents of a single tribe might number thousands. In Syria I had seen the Shammar migrating, a whole people on the move, covering the desert with their herds, and had visited the summer camp of the Rualla, a city of black tents. In northern Arabia the desert merges into the sown and there is a gradual transition from Bedu to shepherds and cultivators. Damascus, Aleppo, Mosul, and Baghdad exert their influence on the desert. They are visited by Bedu, who see in their bazaars men of different races, cultures, and faiths. Even in the Najd the Bedu have occasional contact with towns and town life. But here scattered families moved over great distances seeking pasturage for a dozen camels. These Rashid, who roamed from the borders of the Hadhramaut to the Persian Gulf, numbered only three hundred men, while the Bait Kathir were about six hundred. But these Arabs were among the most authentic of the Bedu, the least affected by the outside world. In the south the desert runs down into the sea, continues into the kindlier deserts of the north, or ends against the black barren foothills of the Yemen or Oman. There were few towns within reach of the southern Bedu, and these they rarely visited.

My ambition was to cross the Empty Quarter. I had hoped that I might be able to do so with these Rashid after we had reached the Hadhramaut, but I realized when I talked with them that by then it would be too hot. I was resolved to return, and was content to regard this first year as training for later journeys. I knew that among the Rashid I had found the Arabs for whom I was looking.

It was on this journey that I met Salim bin Kabina. He was generally known as bin Kabina, ‘the son of Kabina’, who was his mother. In other parts of Arabia it is common practice to call a man the son of his father; here it is more usual to use his mother’s name. Bin Kabina was to be my inseparable companion during the five years I travelled in southern Arabia. He turned up while we were watering thirsty camels at a well that yielded only a few gallons an hour. For two days we worked

day and night in relays. Conspicuous in a vivid red loin-cloth, and with his long hair falling round his naked shoulders, he helped us with our task. On the second day he announced that

he was coming with me. The Rashid sheikhs advised me to take the boy and let him look after my things. I told him he must find himself a camel and a rifle. He grinned and said that he would find both, and did. He was about sixteen years old, about five foot five in height and loosely built. He moved with a long, raking stride, like a camel, unusual among Bedu, who generally walk very upright with short steps. He was very poor, and the hardships of his life had marked him, so that his frame was gaunt and his face hollow. His hair was very long and always falling into his eyes, especially when he was cooking or otherwise busy. He would sweep it back impatiently with a thin hand. He had a rather low forehead, large eyes, a straight nose, prominent cheek-bones, and a big mouth with a long upper lip. His chin, delicately formed and rather pointed, was marked by a long scar, where he had been branded as a child to cure some illness. He had very white teeth which were always showing, for he was constantly talking and laughing. His father had died two years before and it had fallen on young bin Kabina to provide for his mother, young brother, and infant sister. I had met him at a critical moment in his life, although I only learnt this a week later.

We were walking behind the camels in the cool stillness of the early morning. Bin Kabina and I were a little apart from the others. He strode along, his body turned a little sideways as he talked, his red loin-cloth tight about his narrow hips. His rifle, held on his shoulder by its muzzle, was rusty and very ancient, and I suspected that the firing-pin was broken. He was always taking it to pieces. He told me that a month earlier he had gone down to the coast to fetch a load of sardines, and on the way back his old camel had collapsed and died. He confessed: ‘I wept as I sat there in the dark beside the body of my old grey camel. She was old, long past bearing, and she was very thin for there had been no rain in the desert for a long time; but she was my camel. The only one we had. That night, Umbarak, death seemed very close to me and my family. You see, in the summer the Arabs collect round the wells; all the grazing gets eaten up for the distance of a day’s journey and more; if we camped where there was grazing for the goats, how, without a camel, could we fetch water? How could we travel from one

well to another?’ Then he grinned at me and said, ‘God brought you. Now I shall have everything.’ Already I was fond of him. Attentive and cheerful, he eased the inevitable strain under which I lived, anticipating my wants. His comradeship provided a personal note in the still rather impersonal atmosphere of my desert life.

Two days later an old man came into our camp. He was limping, and even by Bedu standards he looked poor. He wore a torn loin-cloth, thin and grey with age, and carried an ancient rifle, similar to bin Kabina’s. In his belt were two full and six empty cartridge-cases, and a dagger in a broken sheath. The Rashid pressed forward to greet him: ‘Welcome, Bakhit. Long life to you, uncle. Welcome – welcome a hundred times.’ I wondered at the warmth of their greetings. The old man lowered himself upon the rug they had spread for him, and ate the dates they set before him, while they hurried to blow up the fire and to make coffee. He had rheumy eyes, a long nose, and a thatch of grey hair. The skin sagged in folds over the cavity of his stomach. I thought, ‘He looks a proper old beggar. I bet he asks for something.’ Later in the evening he did and I gave him five

riyals,

but by then I had changed my opinion. Bin Kabina said to me: ‘He is of the Bait Imani and famous.’ I asked, ‘What for?’ and he answered, ‘His generosity.’ I said, ‘I should not have thought he owned anything to be generous with’, and bin Kabina said, ‘He hasn’t now. He hasn’t got a single camel. He hasn’t even got a wife. His son, a fine boy, was killed two years ago by the Dahm. Once he was one of the richest men in the tribe, now he has nothing except a few goats.’ I asked: ‘What happened to his camels? Did raiders take them, or did they die of disease?’ and bin Kabina answered, ‘No. His generosity ruined him. No one ever came to his tents but he killed a camel to feed them. By God, he is generous!’ I could hear the envy in his voice.

We rode slowly westwards and watered at the deep wells of Sanau, Mughair, and Thamud. There should have been Arabs here, for rain had fallen, and there was good grazing in the broad shallow watercourses which run down towards the Sands across the gravel plains. But the desert was empty and full of

fear. Occasionally we saw herdsmen in the distance, hurriedly driving their animals away across the plain. Some of the Rashid would get off their camels and throw up sand into the air, an easily visible signal and the accepted sign of peaceful intentions. They would then ride over to ask the news. Always it was of the Dahm raiders who had passed westwards a few days before. They were in several parties, returning to then-homelands in the Yemen with the stock they had captured. Sometimes we were told that they were three-hundred strong, and sometimes that they were a hundred; all we knew was that they were many and well-armed. Some Manahil women with a herd of goats told us that forty of them had slaughtered eight of their goats for food three days before. They described how the raiders had lain on the sands and milked the goats into their mouths. These women knew some of the Rashid who were with me and urged us to be careful, but we boasted that we were Rashid, and

‘Ba Rashud!’

(the Rashid war-cry) we were not afraid of the Dahm, who were dogs and sons of dogs. The women answered, ‘God give you victory.’

It was late one evening. We had watered that day at Hulaiya, and now we were camped on a plain near some acacia bushes, among which our scattered camels were grazing guarded by three men. Half a mile away to the west were limestone ridges, dark against the setting sun. The Rashid were lined up praying, their shadows long upon the desert floor. I was watching them and thinking how this ritual must have remained unchanged in every detail since it was first prescribed by Muhammad, when suddenly one of them said, There are men behind that ridge.’ They abandoned their prayers. ‘The camels! The camels! Get the camels!’ Four or five men ran off to help the herdsmen, who had already taken alarm and were hurriedly collecting the grazing camels. Bin Kabina started towards them, but I called to him to remain with me. We had seized our rifles and were lying behind the scattered loads. A score of mounted men swung out from behind the ridge and raced towards our animals. We opened fire. Bin al Kamam, who lay near me, said, ‘Shoot in front of them. I don4 know who they are.’ I got off five rapid shots, firing twenty yards in front of the racing camels, which were crossing in front of us. The dust

flew up where the bullets struck the hard sand. Everyone was firing. Bin Kabina’s three rounds were all duds. I could see the exasperation on his face. He lay a little in front of me to the right. The raiders sought cover behind a low hill. Our camels were brought in and couched. ‘Who were they?’ There was general uncertainty. It was agreed that they were not Dahm or Saar. Their saddles were different. Some said they were Awamir, perhaps Manahil. No, they were not Mahra; their clothes were wrong. A Manahil who was with us said he would go forward and find out. He got up and walked slowly towards the low hill, silhouetted against the glowing sky. We saw a man stand up and come towards him. They shouted to each other and then went forward and embraced. They were Manahil and a little later they came over and joined us. They told us that they were a pursuit party following the Dahm, had seen our camels and had mistaken us for yet another party of Dahm raiders. They had realized their mistake when they heard us shouting to the camel guards, for our voices were not the voices of the Dahm. We had bought a goat that morning, which we had meant to eat for dinner; instead we feasted the Manahil, who were now our guests.