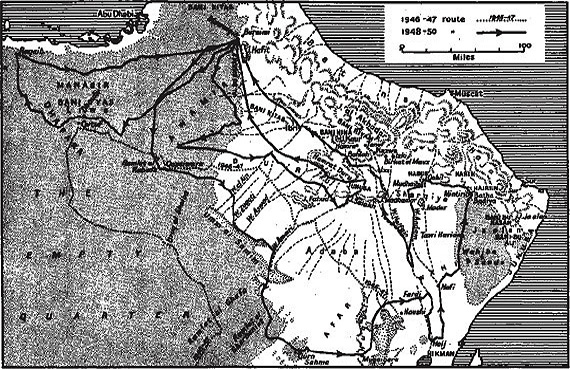

Arabian Sands (44 page)

Authors: Wilfred Thesiger

When I first entered the sands I was bewildered by the utter unfamiliarity of my surroundings and frightened by the feeling that I had only to be separated from my companions to be completely lost in the maze of dunes. Now, like any Rashid, I regarded the Sands as a place of refuge, somewhere where our enemies could not follow us, and I disliked the idea of leaving the shelter they afforded. Nevertheless, it was essential to leave them now and turn eastwards across the Duru plains to avoid finding ourselves on the wrong side of the Umm al Samim quicksands.

Von Wrede was the first European to mention quicksands in the southern Arabian desert. He claimed that in 1843 he had found a dangerous quicksand known as Bahr al Safi in the

Sands north of the Hadhramaut. Bertram Thomas was sceptical of von Wrede’s claim to have discovered the Bahr al Safi and thought that it would eventually be identified with Umm al Samim, of which he had heard from his guides. I myself had travelled through the Sands where von Wrede claimed to have seen his quicksands, and I was convinced that they did not exist there. Many Bedu whom I questioned had heard of the Bahr al Safi. Some identified it with Umm al Samim, others with Sabkhat Mutti, and yet others thought it was somewhere in the Najd; not one suggested that it was to be found in the Sands north of the Hadhramaut. To me it seemed probable that the legend of the Bahr al Safi had grown out of Bedu stories of Umm al Samim. I was determined on this journey to fix the position of these quicksands, which I was certain were here – 750 miles east of the Hadhramaut.

After some discussion we decided to water again at the nearest well in the Wadi al Ain before going southwards along the eastern side of Umm al Samim. I was against visiting these wells, fearing trouble with the Duru, but Salim was confident that he could pass us through their country and, as the Rashid were anxious to spare their camels a long waterless march, I was overruled.

We arrived at the Wadi al Ain after three days and found a little sweet water near the surface. Some Duru were camped near by. We would have preferred to go on after filling our water-skins without attracting the attention of the Duru, but the weather was bitterly cold, blowing a northerly gale, and several of our camels were staling blood. We were afraid that we should lose them if we went on before the wind dropped; here at least there were a few bushes to give them a little shelter.

Early next morning we saw a party of about twenty mounted men approaching, two riders on each camel. They dismounted two hundred yards away where a low bank gave some protection from the wind. They were obviously a pursuit party and we realized that we were in for trouble. Bin al Kamam turned to Salim and asked ‘Who are they?’ and Salim answered ‘God destroy them! It is Sulaiman bin Kharas and others of the Dura sheikhs.’ He watched them for a while and then said,

‘Come, Hamaid, we had better go and find out what they want.’

The Dura rose to greet them and they all sat down in a circle. Soon we heard raised voices. I suggested that we should go over to them, but bin al Kamam said, ‘No, stay here. Leave it to Salim and Hamaid; they are Ghafaris.’ Meanwhile more Dura arrived, among them Staiyun and his son Ali, both of whom came over to us. Bin Kabina started to make coffee and someone placed a dish of dates for them to eat in the shelter of our baggage, but even there the wind soon filled the dish with sand.

Old Staiyun said, ‘The sheikhs are determined to stop any Christian from travelling in our country, but you stayed with me two years ago and are my friend. I and my son will now take you wherever you wish to go, regardless of what the sheikhs may say.’ I thanked him and asked if he had realized who I was when I stayed with him. ‘No,’ he answered, ‘we often wondered who you were and where you came from, but it never occurred to us that you were a Christian.’ After he had drunk coffee, he said, ‘Come. Let us go over to the sheikhs.’ We picked up our rifles and followed him. I greeted the Dura, who now numbered about forty, and followed by my companions, walked down their line, shaking hands with each of them in turn. Then, after we had exchanged the news’, we sat down opposite them, Staiyun and Ali sitting beside me. Salim and bin Kharas went on with their argument. Salim said furiously, The Junuba are accepted as

rabia

by the Dura. By what right do you stop us?’ Bin Kharas shouted back, ‘The customs of the tribes do not apply to Christians.’ He was a thickset man with angry bloodshot eyes, dominant and aggressive. Old Staiyun now joined in: ‘Why do you make all this trouble, bin Kharas? There is no harm in the man. He is known among the tribes and well spoken of. I know him; you don’t. He stayed with me for ten days and did me no harm. On the contrary he helped me. He is my friend.’ Hamaid interposed: ‘Umbarak is Zayid’s friend. He has lived among the tribes for years; he is not like other Christians, he is our friend.’ But bin Kharas shouted, Then take him back to Zayid. We don’t want him here. Take him back at least to Qasaiwara and don’t bring him this way again or we will kill

him.’ Old Staiyun leant forward and said angrily, ‘You have no right to talk like this. God Almighty! I myself will take him through our country in defiance of you and all the other sheikhs. You can’t stop me.’ I looked at the Rashid. Apparently unconcerned, they sat in silence, their eyes moving from speaker to speaker. Bin Tahi poked holes in the ground with his stick; otherwise they hardly moved. They were facing their enemies and very conscious of their dignity. Everyone else started to argue, and five of Staiyun’s relations got up and joined us. Bin Kharas, however, silenced the others, and then declared loudly, ‘We will have no infidel in our land. God’s curse on you, Salim, for, bringing him here,’ and several of those sitting near him voiced their approval of his words. The argument went on and on. More Duru rode up, dismounted, and joined the crowd. Everyone had something to say, and they said it at length and usually several times over. Salim had thrown his head-cloth on the ground as a gesture of defiance, and was now bareheaded in the cutting wind that was blowing clouds of sand into our eyes. Eventually two men who were sitting with bin Kharas took him aside. When they came back he muttered ungraciously, ‘AH right, you may take the Christian southwards along the edge of Umm al Samim until you are out of our country, but you may not water at any of our wells.’ At once the crowd broke up, for all were anxious to get back to the shelter of their encampments. Only Staiyun and Ali stayed with us. As we watched Sulaiman and the others ride away, bin al Kamam said, ‘You cannot trust the Duru. Too many people who travel with them die of snake-bite.’ I remembered how al Auf had used this same expression when I first entered the Duru country two years before. I wondered how we should get back through their country. Unless we could return through the mountains there was no way round it.

Next morning the wind had dropped. We filled all our water-skins, for Staiyun, who offered to come with us, thought that we might meet with further opposition when we tried to water in the Amairi. I asked him to take us along the edge of Umm al Samim so that I could see the quicksands. He said, ‘All right, but there is really nothing to see.’

We travelled across interminable gravel strewn with limestone fragments and bare vegetation, until at last we came to the shallow watercourse of the Zuaqti, defined by a sprinkling of herbs shrivelled by years of drought. Beyond, a tawny plain merged into a dusty sky, and nothing, neither stick nor stone, broke its drab monotony. Staiyun turned to me: There you are. That is Umm al Samim.’

I remembered my excitement two years before when al Auf had first spoken to me of these quicksands as we sat in the dark discussing our route across the Sands. Now I was looking on them, the first European to do so. The ground, of white gypsum powder, was covered with a sand-sprinkled crust of salt, through which protruded occasional dead twigs of

arad

salt-bush. These scattered bushes marked the firm land; farther out, only a slight darkening of the surface indicated the bog below. I took a few steps forward and Staiyun put his hand on my arm, saying, ‘Don’t go any nearer – it is dangerous.’ I wondered how dangerous it really was, but when I questioned him he assured me that several people, including an Awamir raiding party, had perished in these sands, and he told me once again how he had himself watched a flock of goats disappear beneath the surface.

We watered in the Amairi and the few Duru who were there did not interfere with us. In order to link up my present compass-traverse with that which I had made three years earlier in the Sahma sands to the east of Mugshin, I was anxious to visit the Gharbaniat sands to the west of Umm al Samim. Some Duru had told us that these sands were full of oryx; but in any case the Rashid were happy at the idea of visiting them, since they expected to find grazing for their camels there. However, Hamaid refused to agree, saying that he and Salim had come to Qasaiwara not to wander about in waterless sands which offered nothing but hardship, but to take me to Yasir at Izz. Salim had already made trouble. A few days earlier he had suddenly demanded extra money, declaring that he would go no farther with us unless I gave it to him. We had paid no attention but, loading our camels, had started off without him. He had said no more at the time, but I suspected that he had instigated this new trouble. I was

tempted to get rid of him for I disliked him, but the Rashid warned me that, if I did, he, knowing our plans, would thwart us when we tried to enter Oman. I agreed and eventually bin al Kamam took him aside with Hamaid and finally persuaded them to come with us.

Staiyun left from here to return to his encampment, but first he found an Afar to act as our guide until we reached the Wahiba country. This man offered to take us across the southern tip of Umm al Samim. We all disliked the idea of setting foot on it, but he assured us he knew a safe path which would save a long detour, an important consideration as the next well was far away. We started at dawn. For three hours we moved forward a few feet at a time across the greasy surface, trying to hold up the slipping, slithering camels, so that they should not fall down and split themselves. Often our weight broke through the surface crust of salt, and then we waded through black clinging mud which stung the cuts and scratches on our legs. Incessantly the half-bogged camels tried to stop, but we dragged and beat them forward, fearful lest, if they ceased to move, they would sink in too deep to get out again. Uneasily, I remembered stories of vehicles which had sunk out of sight in similar quicksands in the Qatara depression during the war. The others, too, were obviously nervous and bin Kabina voiced our thoughts when he said, T hope to God the whole surface doesn’t break up; I don’t want to drown in this muck.’ It seemed a very long time before we reached the safety of a limestone ridge which marked the firm ground on the far side. From there we saw the Sands: wide-sweeping, warm-coloured dunes dotted with grazing for our camels.

In the evening we discussed where we should go to look for oryx and, as we could not agree, I suggested jokingly that someone should read the sands. Bin Kabina answered, ‘None of us knows how to do it,’ but bin Tahi said, ‘How do you know that? I am an expert at it. My readings always come true. Look, I will show you.’ He smoothed the sand in front of him and with two fingers made a row of dots which he marked off in spans with his hand. Muttering to himself and occasionally stroking his beard, he counted whether there

was an odd or an even number of dots in each span. Then he made some marks in the sand, wiped out the row of dots and started again, still muttering. On various occasions I had watched Arabs reading the sands, and the method which bin Tahi now used seemed identical with theirs. The others watched intently. Finally he announced, There are oryx to the south near Sahma.’ As this pronouncement confirmed the view which he had previously expressed, bin Kabina, who wanted to go to the west, immediately asked, ‘How did you work that out?’ The others were equally sceptical and soon forced the old man to confess that he knew as little about divining as they did. ‘Well, anyway, I made you think I did,’ he chuckled. Bin al Kamam then asked, ‘Where do you want to go, Umbarak?’ and I said, ‘Let’s go to the south. Who knows, perhaps bin Tahi will prove to be right after all.’ And to this the others agreed.

We rode southwards for fifty miles to the edge of Sahma, but though we found fresh tracks we saw no oryx. Near Qurn Sahma we passed an Afar boy whose camels had been stolen by Jumaan, the same man whom we had chased a few weeks earlier near Liwa. The boy, mounted on a half-grown colt, was following his tracks and was already short of water. We advised him to return and collect a proper pursuit party. When he refused, we gave him water and wished him luck, feeling, however, that he would stand little chance if he caught up with Jumaan, for he had only three rounds in his belt and his rifle was an ancient and obviously unreliable weapon.

We arrived nine days later at Farai on the edge of the Wahiba country after watering at Muqaibara, a little-used well on the northern edge of the Huquf, where the bitter water was nastier than any I had ever drank. We had emptied our water-skins the night before and had some difficulty in finding the well, since our Afar guide was confused by dunes, three or four feet high, which he said had not been there when he passed that way ten years earlier. To me it seemed that these tongues of sand were the only landmarks on the level plain that we had been crossing for the past two days.