Arabian Sands (48 page)

Authors: Wilfred Thesiger

I was disappointed that I had been turned back when I had so nearly reached the Jabal al Akhadar, for I would have given much to have explored this mountain. 1 knew, however, that it would be useless to return and try again the following year. Travelling in the desert, we had always been able, when held up, either to profit from the rivalries of the tribesmen, or, if turned back, to reach our destination from another direction. The Rashid who accompanied me were Bedu, at home anywhere in the desert, even in country which was new to them or where the tribes were hostile, but they knew nothing of either the Jabal al Akhadar or of the Arabs who lived there. I had realized even before we had started from Muwaiqih that I could only travel in this mountain with the permission of Sulaiman bin Hamyar. I had reached him, and he had refused me leave to go there.

We arrived back at Muwaiqih ten days later, after travelling by night for the last part of the journey, in order to avoid the Al bu Shams who were on the watch for us. I stayed there for a few days with Zayid before I left for Dibai, taking bin Kabina and bin Ghabaisha with me, for I knew I would not come back and I wanted to have them with me until I left Arabia. On our way to Dibai we stopped for a night in an oil camp that had sprung up near the coast while I had been away in Oman. The ‘camp boss’ told me that they were nearly ready to drill for oil.

Dibai, where we stayed with Edward Henderson and his assistant, Ronald Codrai, in their house beside the harbour, was happily still unchanged. At the oil camp bin Kabina and bin Ghabaisha had not been allowed to share the empty tent which had originally been allocated to me in the ‘European lines’, and I had therefore spent the night with them in the ‘native lines’. Henderson and Codrai, however, were quite willing to treat them as their guests, and gave us a room together. Henderson asked me what to do about food and I suggested that he should make no alterations. As we went in to lunch I said to bin Kabina, ‘While I was with you in the desert

I fed and lived as you do; now that you are our guests you must behave as we do.’ They watched carefully to see how we used the knives and forks and managed with singularly little trouble. They were far more self-possessed than most Englishmen whom I had seen feeding with their hands for the first time. Afterwards I said to them, ‘Your hosts wish you to have whatever you want while you are here. They have asked me to find out whether you prefer to eat our food or whether you would rather have Arab meals.’ Bin Kabina smiled and answered, ‘We shall, it is true, be more comfortable and able to eat more if we feed as we are accustomed, but, Umbarak, do not mention this if it would cause embarrassment. We don’t know your customs, and you must help us now as we helped you in the desert.’

We dined that night with the Sheikh of Dibai on the far side of the creek. The lad I hired to row us over asked if he should wait to bring us back and I told him to return at ten o’clock. As we were coming back to the landing-stage bin Ghabaisha suddenly said, ‘Umbarak, we have done an awful thing,’ and when I asked what was wrong he answered, ‘We have forgotten to bring back any food for our travelling companion.’ Puzzled, I asked whom he meant, and he said, ‘The boy who brought us over.’ I assured him that the boy would not expect it, as the customs of the town were different from the customs of the desert, but bin Ghabaisha shook his head and said, ‘We are Bedu. He was our travelling companion. Did he not bring us here? and we forgot him. We have fallen short.’

On our first day there bin Kabina accidentally shut himself up in the sitting-room and was unable to get out until he attracted my attention by hammering on the wall; but soon both of them were perfectly at home and were fiddling with the wireless and playing Henderson’s gramophone. Henderson and Codrai were endlessly good-natured, particularly as in the early morning it amused my companions, who got up at dawn, to burst into their rooms exhorting them. ‘Up and pray! Up and pray! as they beat the beds with their camel-sticks.

One morning they came back before breakfast from the

suq

in a state of great excitement. As they buckled on their cartridge-belts they told me that a kinsman of theirs had been arrested by the Sheikh of Sharja and that they must go immediately to his assistance. I asked how they proposed to get to Sharja, which was twelve miles away, and bin Ghabaisha said, ‘We will hire a car; give us some money; you know how much a car will cost.’ I suggested that they should wait and get a lift in a lorry which I knew Henderson was sending there later in the morning, but they were impatient: ‘We cannot wait; we must go now, at once. Tell Henderson to send the lorry now.’ I asked, ‘Who is the man? Do I know him? What is his name?’ and bin Kabina said, ‘I don’t know his name, but he is a kinsman of ours. Is that not enough?’ ‘Is he a Rashid?’ I asked. ‘No, he is a Sharaifi.’ By now I knew enough of tribal geneologies to realize that this small and obscure tribe was only very distantly connected with the Rashid, but bin Ghabaisha said, ‘What does it matter? He is a kinsman and in trouble; we must go to his help. Would you have us desert him, Umbarak, when there is no one else to help him?’

They went off in the lorry and came back in the evening. The man had been released before they got to Sharja.

Having come to Dibai by car they had no camels to worry about and were content to remain for a while enjoying this new experience. It would give them something to talk about when they got back to the desert. Meanwhile, they found it pleasant to sit about, fully fed, and with nothing to do but wander into the

suq

and gossip in the shops. I asked bin Kabina if he would care to live here permanently, and he said, ‘No. This is no life for a man. What is there to do?’ I noticed that when they chatted together in the evenings it was of the desert that they spoke, rather than of the things they had seen during the day.

I have often been asked, ‘Why do the Bedu live in the desert where they have to put up with the appalling conditions which you describe? Why don’t they leave it and find an easier life elsewhere?’ and few people have believed me when I have said, They live there from choice.’ Yet obviously the great Bedu tribes of Syria could at any time have dispossessed the weaker cultivators along the desert’s edge and settled on their land.

They continued instead to dwell as nomads in the desert because that was the life they cherished. When I was in Damascus I often visited the Rualla while they were camped in summer on the wells outside the city. They urged me to accompany them on their annual migration, which would start southward for the Najd as soon as grazing had come up after the autumn rains. Only in the desert, they declared, could a man find freedom. It must have been this same craving for freedom which induced tribes that entered Egypt at the time of the Arab conquest to pass on through the Nile valley into the interminable desert beyond, leaving behind them the green fields, the palm groves, the shade and running water, and all the luxury which they found in the towns they had conquered.

Knowing that I should not come back, I advised bin Kabina and bin Ghabaisha to return to their homelands in the south as soon as the weather got cool. Already they had many blood-feuds on their hands, and I feared that they would inevitably be killed if they remained in these parts. The following year I heard that bin Kabina had collected his camels and gone back to Habarut; bin Ghabaisha, however, remained on the Trucial Coast, where his reputation became increasingly notorious. Henderson wrote and told me how he was woken in the early hours to find bin Ghabaisha on his doorstep seeking sanctuary with a badly-wounded man in his arms. They had been raiding camels on the outskirts of the town. Henderson sent the wounded man to hospital in Bahrain, and bin Ghabaisha went there with him. Two years later I saw a report by the Political Resident which stated that the Sheikh of Sharja had succeeded at last in capturing ‘the notorious brigand bin Ghabaisha who had been Thesiger’s companion’ and that he was determined to make an example of him. I was relieved when I heard soon afterwards that the Sheikh had released him after receiving an ultimatum from the Rashid and Awamir.

One evening the Political Officer who had taken over from Noel Jackson came to dinner. He led me aside and said, ‘I am afraid, Thesiger, that I have a rather embarrassing duty to perform. The Sultan of Muscat, his Highness Sayid Saiyid Bin Taimur has demanded that we should cancel your Muscat

visa. I have been instructed to do so by the Political Resident. I am afraid I must therefore have your passport.’ I replied, ‘All right, I’ll get it; but you realize I’ve never had a Muscat visa.’

Although we joked during dinner about a ‘visa for Nazwa,’ I realized that it would not be long before visas really were required, even for travel in the Empty Quarter. Even now I was probably barred from going back there. To reach the Sands, I had to start from somewhere on the coast, and I could no longer land in Oman or in Dhaufar; even if I returned to the Trucial Coast my presence would probably be regarded as an embarrassment by the Political Resident. I recalled that the previous year the Aden Government, hearing that I was planning another journey, had sent me a telegram advising me for my own sake not to enter Saudi territory. Although I had no political or economic interest in the country few people accepted the fact that I travelled there for my own pleasure, certainly not the American oil companies nor the Saudi Government. I knew that I had made my last journey in the Empty Quarter and that a phase in my life was ended. Here in the desert I had found all that I asked; I knew that I should never find it again. But it was not only this personal sorrow that distressed me. I realized that the Bedu with whom I had lived and travelled, and in whose company I had found contentment, were doomed. Some people maintain that they will be better off when they have exchanged the hardship and poverty of the desert for the security of a materialistic world. This I do not believe. I shall always remember how often I was humbled by those illiterate herdsmen who possessed, in so much greater measure than I, generosity and courage, endurance, patience, and lighthearted gallantry. Among no other people have I ever felt the same sense of personal inferiority.

On the last evening, as bin Kabina and bin Ghabaisha were tying up the few things they had bought, Codrai said, looking at the two small bundles, ‘It is rather pathetic that this is all they have.’ I understood what he meant; I had often felt the same. Yet I knew that for them the danger lay, not in the hardship of their lives, but in the boredom and frustration

they would feel when they renounced it. The tragedy was that the choice would not be theirs; economic forces beyond their control would eventually drive them into the towns to hang about street-corners as ‘unskilled labour’.

The lorry arrived after breakfast. We embraced for the last time. I said, ‘Go in peace,’ and they answered together, ‘Remain in the safe keeping of God, Umbarak.’ Then they scrambled up on to a pile of petrol drums beside a Palestinian refugee in oil-stained dungarees. A few minutes later they were out of sight round a corner. I was glad when Codrai took me to the aerodrome at Sharja. As the plane climbed over the town and swung out above the sea I knew how it felt to go into exile.

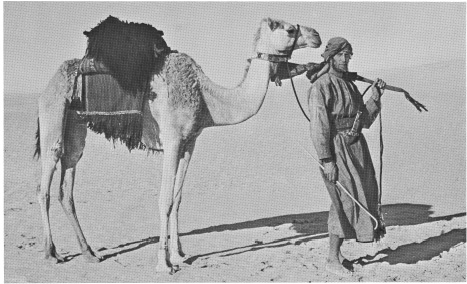

1. Bin Kabina

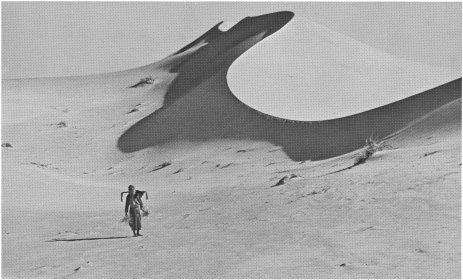

2. The author during the second crossing of the empty quarter