Ardennes 1944: Hitler's Last Gamble (24 page)

Read Ardennes 1944: Hitler's Last Gamble Online

Authors: Antony Beevor

That afternoon a misleading report reached Hodges’s headquarters that Spa itself was threatened. General Joe Collins, who was sitting next to the First Army commander, heard its chief intelligence officer whisper to Hodges:

‘General, if you don’t get out

of town pretty quickly, you are going to be captured.’

‘The situation is rapidly deteriorating,’

the headquarters diary noted. ‘About three o’clock this afternoon there were reports that tanks were coming up from Stavelot headed towards Spa. Only a small roadblock and half-tracks stood between them and our headquarters.’ Hodges rang Simpson, the Ninth Army commander, at 16.05.

‘He says that the situation is pretty bad,’

Simpson recorded. ‘He is ready to pull out his establishment. He is threatened, he says.’ Spa was evacuated, and the whole of First Army staff moved to its rear headquarters at Chaudfontaine near Liège, which they reached at midnight. They learned later that, as soon as they left Spa,

‘American flags, pictures of the President

and all other Allied insignia were taken down and that the mayor released 20 suspected collaborationists out of jail.’

Earlier that evening two officers from the 7th Armored Division, who had just returned from leave, found that their formation had left Maastricht. Setting out to find them, they first went to Spa and in Hodges’s abandoned headquarters they gazed in astonishment at the situation maps which had not been removed in the rush to evacuate. They took

them down and carried on to St Vith, where they handed them over to Brigadier General Bruce Clarke. Clarke studied the maps in dismay. They revealed, as nothing else could, the First Army’s failure to understand what was going on.

‘Hell, when this fight’s over,’

Clarke said, ‘there’s going to be enough grief court-martialling generals. I’m not in the mood for making any more trouble.’ He promptly destroyed them.

Peiper, in an attempt to find an alternative route, had sent off a reconnaissance force of two companies south of the Amblève to Trois-Ponts, a village on the confluence of the Amblève and the Salm. It appears that they became hopelessly lost in the dark. From Trois-Ponts the road lay straight to Werbomont. Peiper, having forced the Americans out of Stavelot, left behind a small detachment on the assumption that troops from the 3rd Fallschirmjäger-Division would arrive, and then set off for Trois-Ponts himself.

The 51st Engineer Battalion, which had been based at Marche-en-Famenne operating sawmills, had received orders the evening before to make for Trois-Ponts to blow the three bridges there. Company C arrived while Peiper’s force was attacking Stavelot and set to work placing demolition charges on the bridge over the Amblève and the two bridges over the Salm. They also erected roadblocks across the road along which the Peiper Kampfgruppe would come. A 57mm anti-tank gun and its crew were pressed into service, as was a company of the 526th Armored Infantry Battalion on its way to St Vith to join up with the rest of the 7th Armored Division.

At 11.15 hours, the defenders of Trois-Ponts heard the grinding rumble of tanks approaching. Peiper’s vanguard included nineteen Panthers. The crew of the 57mm anti-tank gun were ready and its first round hit the track of the leading Panther, bringing it to a halt. The other tanks opened fire and destroyed the gun, killing most of its crew. At the sound of firing the engineers blew up the bridges. Peiper’s route to Werbomont was blocked. The defenders in houses on the west bank opened fire on panzergrenadiers trying to cross the river. Using various ruses, including a truck towing chains to make the noise of tanks and infantrymen firing bazookas to imitate artillery, the defenders convinced Peiper that their force was much stronger than it was.

Furious at this setback, Peiper decided to return to Stavelot and take the road along the north bank of the Amblève instead. His column

thundered along the road towards La Gleize. The steep, forested slopes on the north side of the valley allowed no room for manoeuvre. Peiper still felt that, if only he had enough fuel,

‘it would have been a simple matter to drive through to the River Meuse early that day’

.

Finding no resistance in La Gleize, Peiper sent off a reconnaissance group who discovered a bridge intact over the Amblève at Cheneux. They were seen by an American spotter aircraft flying under the cloud. Fighter-bombers from IX Tactical Air Command were alerted and soon dived into the attack, despite the bad visibility. The Kampfgruppe

lost three tanks and five half-tracks. Peiper’s column was saved from further punishment by the early fall of darkness at 16.30 hours, but the Americans now knew exactly where they were. The 1st SS Panzer Corps, which had been out of radio contact with Peiper, also found out by intercepting the Americans’ insecure transmissions.

Peiper pushed on under the cover of darkness but when the lead vehicle reached a bridge over the Lienne, a small tributary of the Amblève, it was blown up in their faces by a detachment from the 291st Engineer Combat Battalion. Peiper, who suffered from heart problems, must have nearly had a stroke at this further setback. He sent a tank company to find another bridge to the north, but just as they thought they had found one unguarded, they were attacked in a well-executed ambush. It was in any case a fruitless diversion because the bridge was not strong enough for their seventy-two-ton Königstiger tanks. Thwarted and with no more bridges left to try, the column turned round with great difficulty on the narrow road and returned to La Gleize to rejoin the Amblève valley to Stoumont three kilometres further on. Peiper halted the column to rest for the night before attacking Stoumont at dawn. This at least gave civilians in the village the chance to get away.

Peiper had no idea that American forces were closing in. A regiment of the 30th Infantry Division already lay ahead, blocking the valley road another two and a half kilometres further on, and the 82nd Airborne was starting to deploy from Werbomont. The trap was also closing behind him. A battalion from another regiment in the 30th Infantry Division, strengthened with tanks and tank destroyers, relieved Major Solis’s men north of Stavelot, and that evening fought its way into the northern part of the town.

While the 82nd Airborne had rushed on ahead to Werbomont, the 101st started to mount up back at Mourmelon-le-Grand. A long line of 380 ten-ton open trucks were waiting to take up to fifty men apiece. Roll calls by company took place. Men bundled up

‘in their winter clothing looked like an assembly of bears’

. Many, however, lacked greatcoats and even their paratrooper jumpboots. One lieutenant colonel, who had just arrived back from a wedding in London, would march into Bastogne still in his ceremonial Class A uniform. The division band, which had been ordered to stay behind, formed up in angry mood. Its members asked the chaplain whether he could speak to the commander of the 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment, to persuade him to allow them to go. He said that the colonel was too busy, but tacitly agreed that they could always climb aboard with the others. He knew that every man would be needed.

The first trucks left at 12.15 with airborne engineers, the reconnaissance platoon and part of divisional headquarters. The orders were to head for Werbomont. Brigadier General McAuliffe left almost immediately, and two hours later the first part of the main column set off. Altogether 805 officers and 11,035 enlisted men were going into battle. Nobody knew exactly where they were headed, and many thought it strange that they were not going to parachute into battle, but were being transported in like ordinary ‘straight-leg’ infantry. Packed into the open trucks, they shivered in the cold. The column did not stop, and as there was no room to move to the back to relieve themselves over the tailgate, they passed around an empty jerrycan instead. When darkness fell later in the afternoon, the drivers switched on their headlights. The need for speed was deemed to be greater than the risk of encountering a German night-fighter.

When McAuliffe reached Neufchâteau, thirty kilometres south-west of Bastogne, an MP flagged down his command car. He was given a message from Middleton’s VIII Corps headquarters to say that the 101st Airborne had been attached to his command, and that the whole division should head straight for Bastogne. The advance party, unaware of the change of plan, had already gone on to Werbomont, forty kilometres further north as the crow flies. McAuliffe and his staff officers drove on to Bastogne and, just before dark, found General Troy Middleton’s corps headquarters in a former German barracks on the north-west

edge of the town. The scenes of panic-stricken drivers and soldiers fleeing on foot heading west were not an encouraging sight.

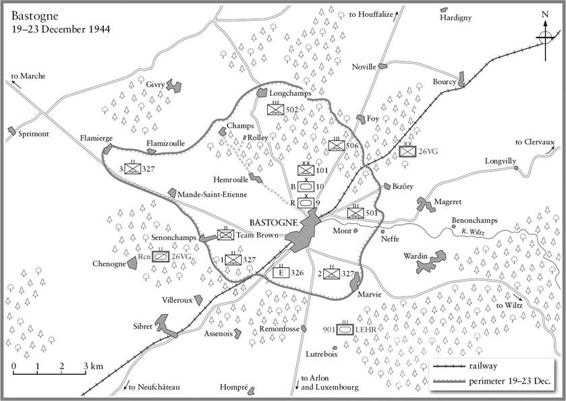

McAuliffe found Middleton briefing Colonel William L. Roberts of Combat Command B of the 10th Armored Division, one of the two formations which Eisenhower had ordered to the Ardennes that first evening. Roberts had a better idea of how desperate the situation was than McAuliffe. That morning General Norman Cota had sent him an urgent request to come to the aid of his battered 28th Division near Wiltz, where the 5th Fallschirmjäger-Division was attacking. But Roberts had received firm orders to go straight to Bastogne, so was forced to refuse. The Panzer Lehr Division and the 26th Volksgrenadier had already broken through just to the north, heading for the town.

‘How many teams can you make up?’

Middleton asked Roberts.

‘Three,’ he replied.

Middleton ordered him to send one team to the south-east of Wardin, and another to Longvilly to block the advance of the Panzer Lehr. The third was to go north to Noville to stop the 2nd Panzer-Division. Although Roberts did not like the idea of splitting his force into such small groups, he did not contest Middleton’s decision. ‘Move with the utmost speed,’ Middleton told him. ‘Hold these positions at all costs.’

In the race for Bastogne, hold-ups on the roads caused tempers to flare in the XLVII Panzer Corps. But the main setback to the timetable had been caused by the courage of individual companies from the 28th Infantry Division. Their defence of road junctions along the north–south ridge road known as ‘Skyline Drive’, at villages such as Heinerscheid, Marnach and Hosingen, had made a critical difference.

‘The long resistance of Hosingen’,

Generalmajor Heinz Kokott acknowledged, ‘resulted in the delay of the whole advance of 26th Volksgrenadier-Division and thereby of Panzer Lehr by one and a half days.’ Company K’s defence of Hosingen until the morning of 18 December, as the commander of Panzer Lehr also recognized, had slowed his division so much that it

‘arrived too late in the Bastogne area’

. This proved decisive for the battle of Bastogne, when every hour counted.

General Cota in Wiltz knew that his division was doomed. He ordered unsorted Christmas mail to be destroyed to keep it from the Germans, so letters, cards and packages were piled up in a courtyard, doused with gasoline and set on fire. During the afternoon, the remnants of the 3rd Battalion of the 110th Infantry fell back towards Wiltz. The hungry and exhausted men formed up to defend the howitzers of a field artillery battalion south-east of Wiltz, while Cota prepared to pull his divisional command post back to Sibret, south-west of Bastogne.

That morning, in mist and drizzle, the spearhead of the Panzer Lehr had finally crossed the bridge over the River Clerf near Drauffelt while the 2nd Panzer-Division crossed at Clervaux, having been delayed by the defence of the town and its castle. Congestion was then caused by tanks breaking down – the Panthers were still the most susceptible to mechanical failure – while the horse-drawn artillery of an infantry division struggling on the same muddy track as armoured formations produced furious scenes.

The commander of Panzer Lehr, Generalleutnant Fritz Bayerlein, a short and aggressive veteran of North Africa and Normandy, blamed his corps commander for having allowed this chaos. Congestion was so bad that the marching infantry of the 26th Volksgrenadier reached Nieder Wampach at about the same time as the panzer troops in their tanks and half-tracks. When vehicles bogged down in the mud, infantrymen took their heavy machine guns and mortars off the vehicles and carried them on their shoulders.

As darkness was falling on 18 December, and the Panzer Lehr advanced on Bastogne, Bayerlein witnessed a tank battle going on near Longvilly.

‘Panzer Lehr, with their barrels turned northward,’

he wrote, ‘passed by this impressive spectacle in the twilight which, cut by the tracer bullets, took on a fantastic aspect.’ In fact one of his own units was involved. Middleton had ordered Combat Command R of the 9th Armored Division to defend the main routes

to Bastogne from the east

. After some initial skirmishes against roadblocks and outposts in the late afternoon, the Shermans and half-tracks of Task Force Rose and Task Force Harper were caught between the spearhead of the 2nd Panzer-Division, a 26th Volksgrenadier-Division artillery regiment, and a company of tanks from the Panzer Lehr. Once the first tanks to be targeted had burst into flames, the panzer gunners kept firing at the other vehicles silhouetted by the blaze. Bayerlein attributed their success to the accuracy and longer range of the Mark V Panther’s gun. American crews abandoned their vehicles whether hit or not, and escaped towards Longvilly.