Ardor (36 page)

Authors: Roberto Calasso

Tags: #Literary Collections, #Essays, #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural

XIII

RESIDUE AND SURPLUS

In that place therefore the blessed god, all-present, sleeping on the ocean, cloaked his night with thick darkness. But a surplus of luminous quality awakened him and he saw the empty world.

—Mah

ā

bh

ā

rata

, 3.272.40–41ab

The whole of Indian tradition, in its various branches, is influenced by a

doctrine of residue

, which can be embodied in three words, corresponding to three successive stages:

v

ā

stu

,

ucchi

ṣṭ

a

, and

ś

e

ṣ

a.

It has a key role as a doctrine, similar to that of

ousía

in classical Greece, in that it suggests the inadequacy of sacrifice (but instead of sacrifice we can also say:

of any system

) in supporting the whole of existence. Something always remains outside—indeed,

has to

remain outside, because, if it were included in the system, it would disrupt it from within. On the other hand, the sacrifice or any system makes sense only if it extends to everything. A compromise therefore had to be established with what was left

outside

, what was left

behind.

So Rudra became V

ā

stavya, the ruler of the place and of the residue. This was the place the gods had left behind to get to the sky. But this place was the whole earth. So the whole earth was the residue.

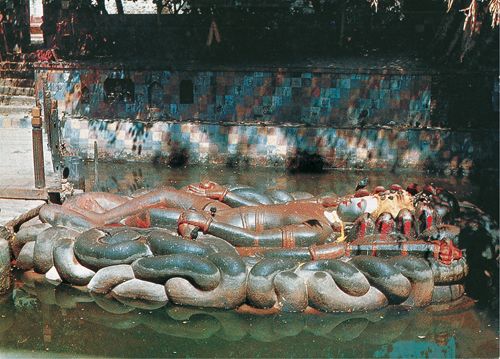

The passage from one epoch to the other was described as being like an enormous fire, a funeral sacrifice in which the fire consumed the whole earth. In the end, all that remained was ash, floating on the waters. Once again, the residue. This ash took the form of a snake, called

Ś

e

ṣ

a, Residue, and also Ananta, Infinite. What at the beginning had been thrown away turned out to be limitless, invincible. The snake arranged its coils into a soft bed so Vi

ṣṇ

u could lie on it. The god slept—or meditated or dreamed. One day a surplus of

sattva

, that luminous thread woven within all that exists, shook him and woke him. And another world sprang forth while a long lotus stalk sprouted from his navel. At the top, a magnificent pink bud came into blossom. And resting on it was another god, Brahm

ā

, who looked about him with his four faces and was puzzled, since “sitting at the center of that plant, he didn’t see the world.” Looking about in all directions he saw the vast lotus petals and then waters and sky, far away. The petals prevented Brahm

ā

from seeing the other god, Vi

ṣṇ

u, from whose navel the stalk had sprouted. Brahm

ā

would one day drop down into that porous fiber to make a new world start.

* * *

The question of residue arises when at last “by means of the sacrifice the gods rose up to the sky.” It could have been the happy ending to their troubled time on earth. But it was not to be so, for that moment marked the beginning of a convulsive, coruscating sequence that the

Ś

atapatha Br

ā

hma

ṇ

a

recounts in its masterly style: “The god who rules the cattle was left behind here: so they call him V

ā

stavya, because he was left behind on the sacrificial site (

v

ā

stu

). The gods continued to practice

tapas

in the same sacrifice through which they had ascended to the sky. Now the god who rules the cattle and had been left behind here saw [all this and said]: ‘I have been left behind. They are leaving me out of the sacrifice!’ He pursued them and with his [weapon] held high he rose up to the north, and the moment when this happened was that of the Svi

ṣṭ

ak

ṛ

t [He-who-offers-well-the-sacrifice]. The gods said: ‘Don’t shoot!’ He said: ‘Don’t leave me out of the sacrifice! Leave an oblation aside for me!’ They replied: ‘Let it be so!’ He withdrew and didn’t shoot his weapon; and injured no one. The gods said to themselves: ‘All portions of the sacrificial food we have prepared have been offered. Let us try to find a way of putting aside an oblation for him!’ They said to the officiant: ‘Lay out the sacrificial plates in the proper succession; and fill them, making an extra portion, and make them once again fitting to be used; and then cut a portion for each.’ So the officiant lay out the sacrificial plates in the proper succession and filled them up, making an extra portion, and he made them once again fitting to be used and cut a portion for each. This is the reason he is called V

ā

stavya, because a residue (

v

ā

stu

) is that part of the sacrifice that remains when the oblations have been made.”

* * *

Sacrifice is a journey above all for the gods—the only way of reaching heaven. But who did the gods sacrifice to, when they rose up to heaven? The elements for the sacrifice had been obtained—desire, to remain in heaven;

tapas

, which the gods practiced; and the material for the oblation (ghee). But there was no one to sacrifice to. Heaven was apparently empty. On this point the texts, so complete in every other detail, are silent. One might suspect, then, that the sacrificial act was effective regardless of whom it was for. Indeed, one could arrive at the ultimate conclusion: that it was all the more effective because the recipient of the sacrifice was not there. One day, K

ṛṣṇ

a taught a doctrine no less paradoxical, in the

Bhagavad G

ī

t

ā

: of sacri

fi

ce where desire is eliminated. This is suggested as a path for mankind, a path that never reaches its destination and one therefore to be continually pursued. But the gods had set their minds on a journey that was to be taken only once. And so they had no wish to renounce desire. If anything, they were more concerned about something else: wiping out their tracks so that people couldn’t follow them: “They sucked the sap of the sacrifice, as bees suck honey; and after having drained and wiped out its traces with the sacrificial post, they hid themselves.” Spiteful gods. But they were equally spiteful toward one of their own. They had abandoned him on earth, at the very place of the sacrifice. He was a god they preferred not to name—and who is not indeed named anywhere in the whole passage except at the end, with a clever device in which his name appears as one of his epithets: Rudra, the Wild One. We can, thus, already see the strange impatience, tinged with fear and hostility, that the gods felt for two divine figures: firstly Praj

ā

pati, the father, who in having intercourse with U

ṣ

as had performed an act that was “an evil in the eyes of the gods,” and then Rudra, this strange god, whom the other gods want to be rid of, for mysterious reasons that are never explained, at the point when they become fully fledged gods, inhabitants of the sky. Even if the texts are more reticent over Rudra than over any other god, the essential points seem clear: the Devas want to get away from Rudra, they want to leave him behind at the

place

(

v

ā

stu

) of the sacrifice, which is also the

residue

(

v

ā

stu

) of the sacrifice. But once the gods have risen to the sky, the whole earth can be seen as a

residue

of the sacrifice. And this residue is powerful and can attack the gods. And so its lord, who is Rudra, retains the capacity to

injure

the gods, as he threatens to do by shooting his unnamed weapon, presumably an arrow. For the gods, therefore, it is not enough to perform an effective sacrifice. They have to

reach a pact

with Rudra, who will otherwise strike them. And a pact, for the gods, is always a new division of portions. This time a division has to be made that includes

Rudra’s portion

:

la part du feu.

And that portion, by definition, will be the

excess

, that surplus which the gods can forgo, so as to ward off Rudra’s attack.

The question remains: how could the gods possibly think of leaving Rudra out of the sacrifice? And why did they want to leave him out? “They did not truly know him,” says the

Mah

ā

bh

ā

rata

, thus revealing what older texts had been silent about. Perhaps they did not know him because in Rudra there was an element resistant to knowledge, of pure intensity, prior to meaning. The gods, though, had based their work—the sacrifice—on the pervasiveness of knowledge itself, on its transparency. They left Rudra out because they rightly suspected that he would have undermined their enterprise from within. But certainly not because Rudra was extraneous or hostile to the sacrifice. When Rudra appeared in the north of the sky, striking terror, bow in hand, his hair tied at the back of his neck in a black shell, the other gods saw straightaway that his lethal weapon was made of the same substance as the first and the fourth type of sacrifice. They also saw that the string of his bow was made of the invocation

va

ṣ

a

ṭ

, which is heard every day in the sacrifices.

This much we can gather, but none of the texts give the reason for Rudra’s initial exclusion. A reason, though, that will become much clearer when Rudra becomes

Ś

iva in another eon and another story cycle, and the tale of his exclusion becomes the tale of

Ś

iva’s exclusion by Dak

ṣ

a from the sacrifice: another event that the gods would seek to hide, since it describes their own defeat. And here a suspicion arises: that the sacrifice claims to be everything, but fails to be so. Every sacrifice

leaves out

or

leaves behind

something that may turn against it: its site, its residue.

Ś

iva is excluded by Dak

ṣ

a because he has offended the brahminic laws, twice showing disrespect: in taking away Dak

ṣ

a’s daughter Sat

ī

and, in a certain moment, not standing up in front of him. But at the same time

Ś

iva cannot be regarded as being

against

the sacrifice. Nor can Rudra, who is called “king of the sacrifice” and “he who brings the sacrifice to its completion.” It would therefore seem that the sacrifice performed by the Devas conflicts with a further sacrifice, that of Rudra and of

Ś

iva, which threatens to harm and cancel out the first—and it may perhaps be the sacrifice that happens

in any case

, that forms part of the cycle of life, of its breath, and can sweep away everything, even the gods. Invasive and ever-present, this sacrifice doesn’t follow an explicit doctrine, but is nevertheless performed. This happens all the time, whether we like it or not, just like the breath within us, which is a continual drawing in from the outside world and a continual expulsion into the outside world, even when it is not subject to yogic discipline. It can therefore be thought of as a continuous sacrifice, which coincides with life itself. When this form of sacrifice appears, there is no choice but to come to an agreement with it, to allow it its irreducible role. Only such a recognition enables the ordinary sacrifice of the gods to be

done well

, as is suggested by the term Svi

ṣṭ

ak

ṛ

t, which is applied to this moment. In a certain way, then, the figure of Rudra and subsequently of

Ś

iva, into whom he is transformed, is the most radical criticism of sacrifice to be found in the world of the gods. But it is a criticism that doesn’t destroy. Indeed, in the end it provides confirmation, further extending the field of sacrifice to cover everything, encapsulating within it all residue.