Are Lobsters Ambidextrous? (5 page)

Read Are Lobsters Ambidextrous? Online

Authors: David Feldman

The beauties of white as proper background even inspired one Local 277 member, Liz Weber, to burst into verse:

…and although we strive for neatness,

getting paint on our clothes is our one weakness.

So what if those colors tend to cling—

we’re in style because…

White goes with everything!

Even if a painter isn’t thrilled with pigment-stained whites, compared to other colored garb, they are a washroom delight. Traditionally, painters used bleach or lye to remove paint from their uniforms: Those that started with dark uniforms ended up with bleached-out, dingy, light-colored ones anyway.

Some other painters we consulted mentioned two other advantages of whites: They are cheaper than dyed fabrics and, because of their color, reflect light rather than absorb it, a small comfort to painters working in the sun-drenched great outdoors.

Submitted by Angelique Craig of Austin, Texas. Thanks also to Howard Livingston of Arlington, Texas; Laura Arvidson of Westville, Indiana; Cristie Avila of Houston, Texas; Tom Rodgers of Las Vegas, Nevada; Adam Rawls of Tyler, Texas; and Karen Riddick of Dresden, Tennessee

.

Why

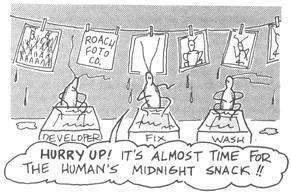

do roaches run away when a light is turned on in a darkened room?

Just as a sunflower is genetically programmed to turn toward the sun, many plants and animals are phototropic—they are genetically programmed to turn away from and avoid the sun. Cockroaches are nocturnal animals, and most species instinctively scurry when exposed to light.

The urban roach has adapted well to its environment. While we are asleep, dreaming away, the roach is free to loot our kitchens as if they were no-cost supermarkets. By roaming at night, it also avoids the rodents that might eat it during the day. At night, the only foes roaches have to worry about are Raid and Combat.

It is impossible to know for sure, since we can’t interview a roach, to what extent the roaches are bothered by the light per se, or whether the scurrying is a genetically programmed response to help roaches avoid predators. Randy Morgan, entomologist at the Cincinnati Insectarium, told us that the speed of a given roach’s retreat is subject to many factors, including its species, the humidity, and how hungry it is.

But why assume that the roach is running because of the light? Maybe it is running away from

you!

Cockroaches have poor eyesight; their main method of detecting danger is by sensing vibrations around them. Robin Roche, entomologist at the Insect Zoo in San Francisco, told

Imponderables

that roaches have two hornlike structures on their back called cerci. The cerci have hairs that are very sensitive to wind currents. So when you enter the kitchen for your midnight snack, chances are the roach senses you not from sight, or by sound, but by feeling the air currents your movement has generated.

At the very least, the roach knows something is moving around it; when you flip the light switch on, an automatic physiological response ensues. If it hasn’t already bidden a hasty retreat, it decides that the better part of valor is to sneak back into the crevice it came from. When you go back to bed, it knows those bread crumbs will be right where you left them before, and it can snack away later in peaceful darkness.

Submitted by Jill Davies of Forest, Mississippi

.

If

moths are attracted to light, why don’t they fly toward the sun?

There is one little flaw in the premise of this Imponderable. Even if they were tempted to fly toward the sun, they wouldn’t have the opportunity—the vast majority of moths are nocturnal animals. When’s the last time you saw one flitting by in daylight? Actually, though, the premise of this question isn’t as absurd as it may appear. For details, see the next Imponderable.

Submitted by Joel Kuni of Kirkland, Washington. Thanks also to Bruce Kershner of Williamsville, New York

.

Why

are moths attracted to light? And what are they trying to do when they fly around light bulbs?

Moths, not unlike humans, spend much of their time sleeping, looking for food, and looking for mates. As we’ve already learned, most moths sleep during the day. Their search for dinner and procreation takes place at night. Unlike us, though, moths are not provided with maps, street signs, or neon signs flashing “

EAT

” to guide them to their feeding or mating sites.

Over centuries of evolution, moths have come to use starlight, and particularly moonlight, for navigation. By maintaining a constant angle in reference to the light source, the moth “knows” where to fly. Unfortunately for the insects, however, humans introduce artificial light sources that lull the moths into assuming that a light bulb is actually their natural reference point.

An English biologist, R.R. Baker, developed the hypothesis that when moths choose the artificial light source as their reference point, and try keeping a constant angle to it, the moth ends up flying around the light in ever-smaller concentric circles, until it literally settles on the light source. Baker even speculates that moths hover on or near the light because they are attempting to roost, believing that it is daytime, their regular hours. Moths have been known to burn themselves by resting on light bulbs. Others become so disoriented, they can’t escape until the light is turned off or sunlight appears.

So don’t assume that moths are genuinely attracted by the light. Sad as their fate may be, chances are what the moth “is trying to do” isn’t to hover around a porch light—the only reason the moth is there is because it has confused a soft white bulb with the moon. The moth would far rather be cruising around looking for food and cute moths of the opposite sex.

Submitted by Charles Channell of Tucson, Arizona. Thanks also to Joyce Bergeron of Springfield, Massachusetts; Sara Anne Hoffman of Naples, Florida; Gregg Hoover of Pueblo, Colorado;

Gary Moor of Denton, Texas; Bob Peterson, APO New York; and Jay Vincent Corcino of Panorama City, California

.

Why

do some nineteen-inch televisions say on the box: “20

IN CANADA

”?

Do televisions grow when exposed to the clean air in Canada? Are Canadian rulers more generous? Do televisions bloat when transported over the border?

None of the above. What we have here are two bureaucratic mechanisms that have agreed to differ. In Canada, the size of a television is measured by determining the size of the picture tube from one corner to its opposite diagonal corner. But in the U.S., the

viewable

picture is measured: from one corner of the picture itself to its opposite along the diagonal. Those cropped corners on the monitors reduce the viewing size by approximately one inch.

The picture tube is always a little bigger than the measurable picture, which is why Canadians might think they are getting ripped off when they try to confirm the measurements of their sets. Steve Sigman, vice-president of consumer affairs for Zenith, told

Imponderables

that the television picture shrinks naturally with age. Luckily, the shrinkage materializes along the edges of the monitor. By supplying a little extra picture tube, the manufacturer insures that the consumer will get the whole image for a long time.

Submitted by Mary Mackintosh of Sacramento, California

.

Why

does an old person’s voice sound different from a middle-aged person’s?

To unravel this Imponderable, we spoke to our favorite speech pathologist, Dr. Michael J. D’ Asaro, of Santa Monica, California, and Dr. Lorraine Ramig, who has published extensively on this very subject. Both of them named three characteristics of the aged voice and found physiological explanations for each:

1. The elderly voice tends to be higher in pitch. This characteristic is much more noticeable among men because hormonal changes at the onset of menopause work to lower the pitch of older women. As we age, soft tissues all over our body shrink in size. The vocal cords are no exception. As we learned in

Why Do Clocks Run Clockwise?

, there is a direct correlation between the mass of the vocal cords and pitch: The larger the vocal cords, the lower the pitch.2. The elderly voice tends to be weaker in strength. D’ Asaro points out that another characteristic of aging is increased stiffening of joints, which reduces amplitude of motion:

In the voice mechanism, the result is reduced volume, especially if the respiratory system is also reduced in capacity. The shortness of breath reduces the motive power of the voice, the exhaled breath.

Ramig adds that the degeneration of vocal folds compounds the problem of creating enough air pressure to fuel a strong voice.

3. Many elderly people experience quavers or tremors in the voice. Again, many old people experience tremors in other muscle groups, as they age, as part of a decrease in nervous system control. Tremors in the laryngeal muscles produce the Katharine Hepburnish vocal quavers we associate with old age. Frequently, serious neurological disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease, are also responsible for severe tremors in the voice.

Ramig told

Imponderables

that not every old person experiences these symptoms, so we asked her if there could be a psychological component to the stereotyped notion of the aged

voice. She responded that in many cases, there very well might be. Certainly, the strong, unwavering voices of numerous elderly actors and singers betray their age. Do these young-sounding performers have different anatomical equipment than others of their age? Does their constant training and projection of their vocal equipment help maintain their laryngeal muscles in fighting trim? Or does their active lifestyle keep them from succumbing to the apathy of some of their age peers? These are the types of further Imponderables that will keep Ramig and her fellow researchers knee-deep in work for years to come.

Submitted by Herbert Kraut of Forest Hills, New York

.

Why

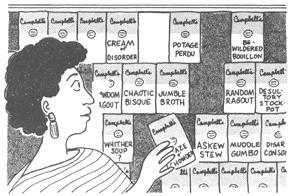

is there usually no organization in the shelving of soup cans in supermarkets?

Few grocery store experiences are as frustrating as trying to find your can of split pea soup amid a sea of red and white. Ninety percent or more of most soup sections are filled with Campbell Soup Company products, and our correspondent wondered why soup lovers weren’t given a break.

Perhaps, our reader speculates, the soups could be arranged alphabetically. But then would cream of mushroom soup be filed under “C” or “M”?

No, organization by genre seems more logical. Indeed, this is what Campbell tries to do. Unfortunately, although Campbell suggests a shelving plan for retailers, grocers ultimately have “artistic control” over how and where the soup is shelved.