Aristocrats (59 page)

Ardglass Castle had come from Lord Charles Fitzgerald, Ogilvie’s first pupil at Black Rock. Lord Charles had been estranged from the family since he voted for the Act of Union and accepted a government post. When he died in 1810, Ogilvie had paid off his creditors and taken over the estate. The humble teacher who had turned stepfather now became inheritor.

Ogilvie was no longer interested in estate management. He wanted to be a master of the water not the earth. After he took on the estate he turned his attention to the harbour at Ardglass, designing and building a long retaining wall out into the sea. This pier, as he called it, was a massive structure over half a mile long and fifty feet in height. It made Ardglass harbour into a safe haven where wandering ships and navy patrols could find shelter from the murderous waters of the Irish Sea. The sea roared against the pier’s walls in storms, black and frothing grey at the surface. Within the pier’s protective arm was the harbour, where battered vessels rested.

Ardglass pier was a structure of the mind as well as a massive physical presence. The maniacal fervour that Ogilvie put into its building belonged to the new, Victorian, age. Curling 3,000 feet out into the sea, and rising many feet above it, the pier was eloquent of the desire for domination and control. Ogilvie, and many who came after him, no longer saw the sea as something sublime and terrible, beyond man’s mastery. It had become an unconquered place, an element that impeded trade, separated man from man and offered resistance to those who sought to control it. So it must be surveyed, mapped, civilised and brought into harbour. As stone after stone was lowered to the seabed beyond Ardglass, it was not just a

retaining wall that was being constructed, it was a way of seeing the world. Yet the sea was resistant, chafing at the restraint, fighting back and remaining, for all man’s best efforts, dangerous and estranging.

Ardglass was Ogilvie’s monument to himself, a confident and even aggressive testimony to his will to succeed in a hostile environment, against all the odds, and on his own terms. ‘I am sorry that I undertook it at so late a period in my life,’ he grumbled. But he went on, and after the harbour was finished he built a life-boat station as well, with a life-boat to save those who could not make it to the harbour’s safety.

Like his pier, Ogilvie endured, living almost until the dawn of the new age. He died at the age of ninety-two, five years before Victoria came to the throne, and crossed over to another shore from which no human ingenuity could find return.

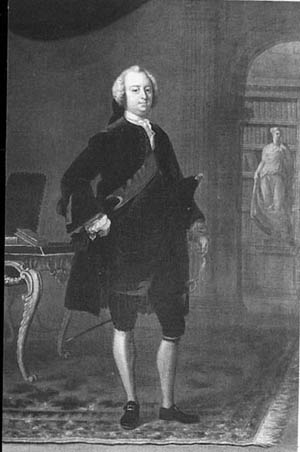

The Lennox girls’ father, Charles, second Duke of Richmond, painted by Charles Philips in the late 1740s as a courtier and collector.

Louise de Kéroualle, Charles II's ‘young wanton’ and subsequently Lennox family matriarch.

The second Duke of Richmond with Sarah his wife by Godfrey Kneller, early 1720s. The Duchess wrote to her husband, ‘I love you exceedingly’ and he called her ‘the person in the whole world I love the best’.

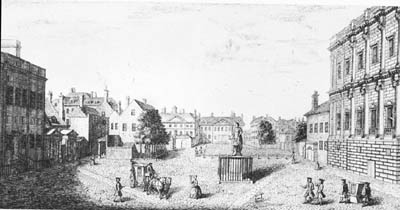

The Privy Garden in 1741, much as it would have looked to Caroline as she ran away from home in 1744. Richmond House is to the right of the trees in the middle distance.

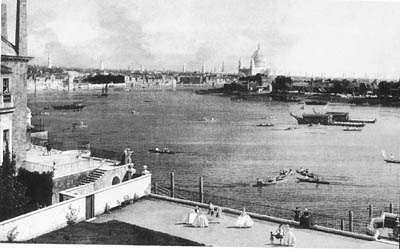

The Thames from Richmond House Terrace by Canaletto, 1747.

Looking the other way from Richmond House, Canaletto’s view of the Privy Garden, with a servant bowing to the Duke of Richmond by the gate of the stable yard.

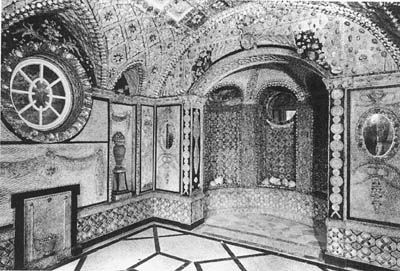

The shell house at Goodwood, designed by the Duchess and her daughters in the 1740s.

Caroline, voluptuous in Turkish masquerade costume shortly before her elopement. ‘Her eyebrows and forehead are charming,’ Emily wrote.

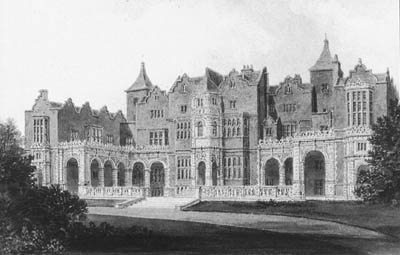

The north front of Holland House, sketched in 1898, but much as it was when Caroline and Henry lived there.

Henry Fox as a self-promoting gigolo, painted in Rome by Antonio David in 1732, when he was on tour with his mistress, Mrs Strangways-Horner.