Arnold Weinstein - A Scream Goes Through The House (11 page)

Read Arnold Weinstein - A Scream Goes Through The House Online

Authors: What Literature Teaches Us About Life [HTML]

We find in Munch's work an astonishing kind of creatural grammar, a syntax of sorts, that seems to say: our affective and experiential lives are punctuated by key episodes of explosive, unhinging feeling, episodes that attend the temporal trajectory of the body as it moves from birth to death, with all the varieties of sickness and mania and fear and desire in between. What seems to undergird this body of work is a conviction that our episodes of upheaval have a special graphic character and can be represented in painting, lithograph, and woodcut. Munch's fame, I would submit, hinges on these qualities, this fidelity to feeling that surfaces over and over in his work; it has earned him a reputation for precariousness, neurosis, melodrama, and even posturing, but it is time to reconceive these matters, and to appreciate his power as por-trayer, not only of libido and affect, but of the social pathways such forces take, pathways of a new human geography.

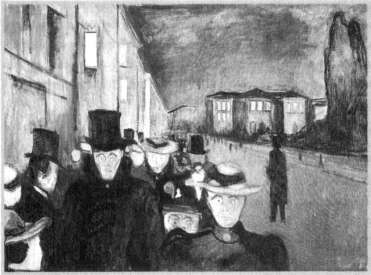

Evening on the Karl Johan,

Edvard Munch, 1892.

The irresistible segue from Blake and Baldwin to Munch passes through the painter's famous

Evening on the Karljohan,

done in 1892 and fully illustrative of the mature Munch style. A century after Blake diagnoses his fellow Londoners, and well before Baldwin depicts Harlem suffering, Munch passes in review the citizens of Christiania (today's Oslo). He does not focus on the chimney sweeper or the soldier or the harlot or the teacher or the musician or the addict, to make his indictment; instead, he renders the parade of proud burghers themselves, making their ritual procession down the main thoroughfare, the Karl Johan, to see and to be seen, a consummate moment of social vindication, meant to shore up these citizens in their sense of gravity and purpose. Munch had dealt with crowd scenes earlier, in his realist portrayal of the

Military Parade on the Karljohan,

and in a pointillist version as well.

But none of these earlier forays prepares us for the march of zombies that we encounter here. On the one hand, Munch's crowd is a new

urban constellation, with a form and synergy that accompany the growth of city populations and that intrigue the nineteenth-century artist and writer: Poe's "Man of the Crowd" and Baudelaire's "Les Foules" ("Crowds") testify eloquently to the explosive albeit anonymous energies to be found here, the sort of thing already at hand in the mass uprisings of the French Revolution. But merely to mention this activist model of the crowd is to measure how radically different Munch's rendition is. These denizens of Christiania would appear to be ghouls, the walking dead, and if we seek parallels with literary figures, one might invoke Thoreau's contemptuous reference to "the mass of men who lead lives of quiet desperation," except that this mass is represented by Munch in surreal, ghastly form now.

Above all, Munch reveals here his soon-to-be trademark style of vacancy and blankness, of white, featureless, hollowed-out faces, spectral countenances with gaping, staring pinpoint eyes, frozen and hieratic in their ghostly parade. No rippling energy in sight here, not even any signs of the picturesque variety that engaged other writers and artists. Instead, Munch has, as it were, plunged into the interior, has laid waste to any psychologizing or affective signs, has produced a spectacle as eerie and depleted and ghostly as some of the arctic landscapes in Melville's sublime chapter in

Moby-Dick

on "The Whiteness of the Whale," where he too elects to go "in," to peel away all the colorful surface trappings that give point to our variegated phenomenal world, so as to settle into the Nothingness that is his real interest.

Munch is Melville's fellow traveler in this regard, and his spectral citizens seem risen from the dead, like some kind of Last Judgment where the dead resurface (resurface as surface), put on their frock coats and top hats and fine gowns, while remaining dazed mannequins, moving (being moved?) in mass formation, but will-less and soulless. We are tempted to fast-forward to the great Fascist crowds of the 1930s, but Munch's emphasis is on the spectral, insubstantial character of these denizens, already prefiguring T. S. Eliot's "hollow men." Their performance gives the lie to all notions of stability, solidity, and solidarity

(virtues they seek to display), and the self-congratulatory belief system that finances such rituals and parades has been eaten away entirely, turned inside out.

Munch's breakthrough here is to have worked through negation and erasure, to have refrained from all surface notation, in such a way as to yield a result of shocking power and violence.

Evening on the Karl Johan

jolts us in his depiction of modern life, because it forgoes any minute particulars—grimace, pain, suffering, even delight—in order to land at rock bottom, to get to the horror that lies underneath. Munch's people have bottomed out, are shown to inhabit a sphere beyond emotion itself, a blankness that seems prior, a bedrock of Nothing that all our song and dance seeks to camouflage. Yet—and here is the miracle—this painting broadcasts the same "marks of weakness, marks of woe" that characterized Blake's Londoners and Baldwin's denizens of Harlem. This, too, is in some terrible sense, a community, even a family of sorts, a whole class of like-minded, like-appareled citizens, aware of the surface features that unite them, wholly unaware of the inner void that unites them. All of the vacancy, the sucked-out vacuum of these faces and lives, exerts an irresistible pull on the spectator, draws us in, makes us gauge the horrible theft (of feeling, or meaning, of reality) that has taken place here. Munch is cunning in his use of blankness and emptiness, as if he knew that the viewer not only would rush in to fill the gap, but would experience the affective black hole as the true horror of these lives, the final record of what life has done to them.

And that is what lays ultimate claim to our attention. Through Munch we see what is not otherwise visible: the sickness at the core of things. This mob-gestalt that seems to flow down the Karl Johan, less animated than even the windows of the buildings, is contaminated, sick unto death, as Kierkegaard might have said, a billboard for epidemic plague. Such a painting obliges us to ask if, indeed, the human soul might be representable, representable most horribly as absence, vacancy. These figures are demonstrably paying the price for the culture that has formed them: their hollowness seems to be a form of "scalp-

ing," a lifelong process of erosion that we now see in its graphic insolence. An entire material culture (of surface prosperity, of agendas and plans, of "success" as something real) seems on the block here—seen, drawn, painted, weighed, and found horribly wanting—as the artist brings us into his field of vision. No plaint is heard, yet this piece seems dirgelike all the same, an urban portrait of hell, not the fiery traditional hell we usually imagine, but the icy hell of erasure and nullity. Could any of us have seen this, had we been on the Karl Johan ourselves, even had we been Edvard Munch, as depicted (very likely) in the isolated figure who moves upstream, against the flow of the crowd?

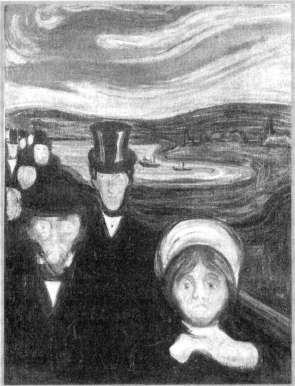

The painting

Anxiety,

Munch's reworking of the same cast of characters, positioned this time on the bridge that is to reappear in some of his most famous works, gives us a close-up into these vacuous faces, and the backdrop of the swirling waters and sinuous orange-red sky announces even more clearly existential disaster at hand. No longer in touch with the apparendy solid pavement of the Karl Johan, these wanderers on a bridge are suspended over the void, heightening even further their precarious ontological footing, hinting at the void within. Once again we note the psychic cancellation, and their dazed pilgrimage, their endless trek across a landscape of water and sky, makes them seem like aliens from another world, trotted out in their bourgeois finery but with no place to go. Again Munch's cunning art pays off: where, we ask, is the anxiety itself, since these faces are so blank and inexpressive? But the collective portrait of slipped gears, of hypnotic trance, looks like a ritual mix of death-by-water and death-by-fire, as if the mouth of hell had opened to expel this itinerant troupe, with lots more where they came from, marching both from and to oblivion. Not only is purposiveness cashiered, unthinkable, here, but we gather that this is what anxiety may actually be: our structural exiled condition, our dance of sleepwalkers. In painting after painting, Munch tells the story of the emperor's new clothes, tells it by decking out his burghers in new clothes in order to point up their absolute vapidness. Anxiety relates to our dawning awareness of fraud and deception, of the lie built into the system.

Anxiety

(painting), Edvard Munch, 1894.

Yet, it seems to go still further than this: we sense here that anxiety— a busy term, a notion of sound and fury turned inward, an aggressive notion, something implosive and energetic in its own way—is ultimately not tumultuous at all, but is the core blankness that is all, and on this reading anxiety is not so much a response to life as its ultimate precondition, the originary, residual horror below the skin, simply

there.

This view, while not very pretty, has at least the tonic virtue of restoring something of the priorities (priorities in literal sense: that which is prior) that the sick and the hurting have always known, so that anxiety is the field we reenter in moments of pain or capsizing, experienced now as an

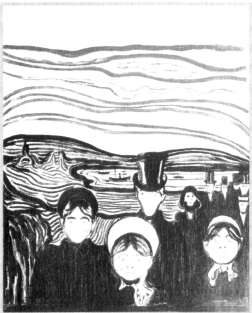

Anxiety

(lithograph), Edvard Munch, 1896.

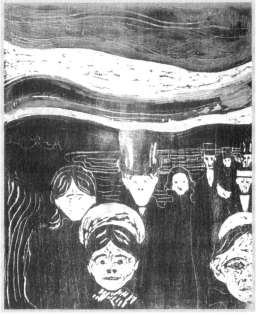

Anxiety

(woodcut), Edvard Munch, 1896.

awful homeland which convention and good luck and health have deceptively painted as accidental, occasional, and escapable. Munch knows it to be the place we live in. The "we" counts here, as strange counterforce to the solipsism usually identified with anxiety, as if Munch were intent on communalizing horror.

And he seems to revel in ways of saying and showing it. Consider the variations of this motif as they appear in lithograph and woodcut, yielding an ever-simpler and more drastic equation of exodus and fall. In the lithograph the swirling natural currents of sea and sky announce even more forcefully the theme of cosmic power and human incapacity, whereas the woodcut seems to go still further, to reveal the very scars and sores lodged in the soul, the scars and sores that are the soul. Anxiety as truth, not as response. Here is Munch's news: within us is the horror, just beneath our surface composure lies the sea of terror. Kafka once wrote that art is the ax that chops into our frozen sea; in Munch that sea is on show.