Arnold Weinstein - A Scream Goes Through The House (12 page)

Read Arnold Weinstein - A Scream Goes Through The House Online

Authors: What Literature Teaches Us About Life [HTML]

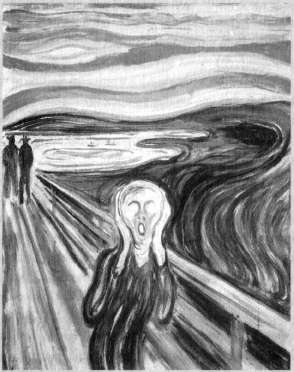

I realize that this account of both Munch and human feeling may appear impressionistic and sensational. But Munch's work announces a rival logic to that which regulates our daytime and scientific thinking (as well as the discourse of both the academy and the street). Blank though his pieces seem to be, they posit affect—not noisy affect, just horror— as the ground we live on (the vacuum under the ground we live on), and thereby give the lie to our brave postures of composure, control, and capability. Anyone who is sick or suffering, who has experienced anxiety, has bitten into Munch's sour apple, has sensed the frequent specious-ness of civilized forms, ranging from the black suits of the bourgeoisie to more serious matters such as unified personality, meaning in life, and sanity itself.

If Munch is right in such depictions, how fraudulent are our customary forms and measures? Something tonic, perhaps even sustaining and inspiriting, may be brought about by such work, because it recon-ceives our libidinal bases, offers a kind of halfway house for all who know whereof he paints. I would argue that—contrary to popular be-

lief—no one has ever been depressed by Munch, but that many have felt both gratitude and recognition at the tidings he brings.

Evening on the Karl Johan

and

Anxiety

do not quite say "Join the crowd," but they are strangely inviting nonetheless, implying that we, even at our lowest, especially at our lowest, have compatriots. The world, Munch seems to announce, only pretends to be bluff, healthy, and functional, but underneath it is all frozen sea. I hardly want to claim that such work makes anyone delirious with joy, but it is reassuring in its peculiar fashion, and it in fact reinstates something of that "solidarity" which seemed initially to be its great target.

Munch travels far down the road of psychic portraiture in his effort to redraw our map, to chart our actual emotional traffic and whereabouts. In many instances we end up with shimmering canvases that remain enigmatic, that seem to hint at a propriety and causality on the far side of our normal habits of reason. Among these

poetic

works I'd put

Red Virginia Creeper

close to the top of the list. Here we see the frontal suffering figure (based on Stanislaw Przybyszewski, who was a player in Munch's erotic entanglements, whose face Munch enlists over and over to depict misery) whose blank, hollow-eyed look defies us to make sense of things. And with good reason: all we can make out is a stately house covered with Virginia creeper (or "Red Vine" as the piece is also known), positioned in an exceptionally barren landscape, with truncated tree and prisonlike white fence. But the more you look at this piece, the curiouser it becomes, the more you start to negotiate the scream that is going through it, and thus you entertain the view that this haunted house that looks like it has skin cancer is somehow an expression of the sufferer's psychic condition. In this light, you can regard the path that seems to flow out of the house as a river of sorts, an imperious flow that then produces—lo and behold!—our hollow-eyed ghoul as its result, giving us the feeling that he is actually swept along by this current, that in about thirty seconds he will disappear from the canvas, carried off to wherever Munch's gallery of the damned ends up.

You'll note that I am treating this painting as if it were precisely a

Red Virginia Creeper,

Edvard Munch, c. 1900.

kind of waterway, as if looking at it were an odd form of rafting, but the flux in question is sentience, not water. Reading the piece in this fashion entails parsing it, espying its odd emotive syntax, its riddling way of positioning us in the world, as if to say: the realist models you believe are harmless and nice enough in their way, but they are worthless when it comes to our actual arrangements, our actual proximities, distances, and relations. Here would be a form of portraiture that cashiers the Newtonian worldview by inventing its own psychic landscape—a landscape that is not fantastic at all, that consists of things we recognize, but now these things

speak

us—as a way of reconfiguring who we are. A house with red vines, a picket fence, a barren tree, and a man who looks like he has just come from a jaunt in hell: discrete items? or a fearful symphony? or a canny landscape that

says

this man's misery and lostness? or an infernal Halloween scene, replete with lit-up haunted house, that vomits out its diseased, crazed occupant? I am intentionally rhapsodic

here, because I feel that our most intense emotional states

defy representation.

Suppose you are feverish (with jealousy or fear or desire or just plain fever itself) and it all rages inside: how could someone depict this? Suppose you are chronically ill or severely depressed or just plain out of sorts: could this be shown? We need to see Munch's strange canvases along these lines, as the translation of a psychic state into a material language of form and color.

Munch's paintings imply that the true career of body and soul constitutes a social, spatiotemporal story that has never been told. Sickness and death are among the prime movers, but hardly the only ones. The discovery of

life

can be just as unhinging as that of death, as I will show in the following chapter when I discuss Munch's

Puberty.

Puberty, like sexual desire, can be experienced as something distinctly mutinous, as a revolt coming from quarters we (when prepubescent) have doubtless known but never paid attention to. All of a sudden, somatic alterations and "messages" such as tingling, yearning, even ecstatic capsizing, inform the occupant of the body of new and imperious tidings. Munch's work sensitizes us to our strange conditions as inhabitants of bodies, as subjects of a somatic order that follows its own rules, plays out its own logic, and leaves us with the challenge of domesticating and personalizing this generic activity.

Is this not also the chilling and inescapable message that illness brings home to us: that our bodies have a life of their own, a life we essentially follow rather than lead, despite the hubris of our conceptual habits? Fever makes joints that we never knew we had ache; makes walking and being upright as difficult and miraculous an event as the history of evolution tells us it is; pain skews our perceptions, addles our judgment, makes much of our well agenda meaningless (seen at last for its superficiality), while what really counts is: no more pain. Munch helps us understand the body's despotism. In pleasure and in pain, the body speaks and we—well, we listen. And must come to terms with the star-ding news that this speaking body is us. To be sure, many, many painters have done homage to the authority of the human body, but few have

The Family at the Road,

Edvard Munch, 1903.

sought its peculiar grammar and syntax in the way Munch has; few have positioned it in our life trajectory—temporally and morally—quite the way he has. Looking at Munch's depiction of bodies in thralldom to the great forces welling up in and out of them helps us to citizenship rights in the somatic country we inhabit.

Battening on to crises and moments when the body speaks or alters, Munch turns out to be a wonderful painter of children, as if he knew that they were truly different, anthropologically different. The group por-

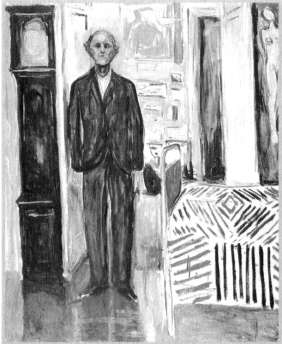

Self-Portrait: Between Clock and Bed,

Edvard Munch, 1940.

traits of children that he did for many of his wealthy patrons are suffused with this awareness, and the dramatic contrast between ages is captured in works like

The Family at the Road

where cliches such as "generation gap" attain their full resonance, as we measure the vertiginous existential space that separates these four figures: doll, daughter, mother, and grandmother. And yet, here too, they are unforgettably framed as a unit, as a legend about the familial shape of passing time, the female contours of history.

Munch is arguably among our very greatest painters of old age, of aging itself as the fascinating and terrible cost of living. The ruthless self-portraits that Munch carried out in the last decades of his very long life, with special (often queasy, always scientific) emphasis on episodes

of sickness and impending physical failure, reach their culmination in his

Self-Portrait: Between Clock and Bed,

done in 1940, a weird companion piece to

Puberty,

but now seen from the final phase of the trajectory, looking backward rather than forward. The frail, soon-to-die old man stands (barely stands) next to the two indicting fixtures that broadcast his insufficiency: the clock that serves as bell-toller, with or without hands, and the bed that awaits those who can no longer stay upright. Yet, as critics have recognized, this is a painting with great charm and wit. The bed cover is an explosion of saucy living color and vibrant pattern, seeming to speak a painterly language of gaiety that knows only life, not death. The old man stands in a doorway, and behind him we see not just a room but a world: a brilliant yellow wall filled with paintings, his paintings (his flesh and blood?) that cannot age or grow frail or die. And we espy still another door, this one darker, half open, leading to a shadowy corridor through which the painter will ultimately exit.

At farthest right we look at the painted human body that is the fundamental currency of Munch's art. This painting is, in its way, quite as philosophical as Picasso's

Les Demoiselles d'Avignon,

in that it proposes for our inspection a number of places, of sites, each asking us to gauge what lives and what dies. The fleshly tenement will fall, but the painted one will stand (however precariously) forever. One remembers, in looking at that vivid space behind the old man—lit by his work, yet containing dark passages—Montaigne's splendid phrase for the thinking subject's inner sanctum, "

l'arriere boutique''''

(back room). Munch's

ar-riere boutique

is the world he has made, the material testimony of work and time: a room of one's own and a family of one's own. We would be hard put to name another painting that shows us more poignantly, more religiously, the fate of flesh and the triumph of art, with the additional, self-evident proviso that the painting itself, albeit done by a man approaching eighty, joins the fray, is forever on the side of the living.

I want to close my discussion of Munch by focusing on what is unquestionably his most notorious work,

The Scream,

a painting that stands in the minds of many as a watershed artwork, a prophetic gate-