Arnold Weinstein - A Scream Goes Through The House (26 page)

Read Arnold Weinstein - A Scream Goes Through The House Online

Authors: What Literature Teaches Us About Life [HTML]

ing stock of information, of exposures; much like our body darkly processes its poisons over the years, our minds too are darkrooms where we are always "developing" the negatives.

With that last phrase, I return to the diagnostic impulse so central to the exposure scenario, especially in its final phase, which is associated with photography and the development of visual images. I have wanted to emphasize our subjection over time, our exposure over time, to forces that gradually and invisibly shape or deform us, both physically and mentally, in order to underscore the primordial role that time plays in this dynamic. Knowledge would then be a kind of temporal narrative, entailing exposure, development, and discovery. Such knowledge is inherently belated, after the fact. Finally, such knowledge is frequently (far more frequently than we realize, given our craving for on-the-spot readings) conjectural, a tentative sighting on a curve, an interpretive construct that is itself conditioned by other contextual forces. It is worth bearing all of these points in mind as we now move more frontally into issues of mapping and imaging, of exposure as a picture of the subject's truth, either somatic or moral.

I think of the remarkable literary invention of the French novelist Boris Vian: a special pistol that he names the

arrache-coeur,

the "heart-ripper"; you aim it at someone, fire, and their heart then moves out of their body, becomes at last visible, and they die. Much to unpack here: our own hearts remain murky to us, despite the EKGs we might obtain on the one hand, or the soul-searching we might do, on the other. Can it be accidental that this key organ of life becomes knowable only at death? Could such "final" readings be lethal? Here would be a grim version of the Pauline fable: not only do you have to die to accede to the truth, but the truth itself kills you. Of course, "reading" the heart means different things for the cardiologist and for the lover, but expectations of transparency in either realm are often dashed.

There are many reasons for being impatient with mystery. Our sanity seems to require that events and acts make sense. Whether it be the news reports on world affairs, the behavior of friends, lovers, and col-

leagues, or the sensations of our own body and inclinations of our own heart, we want and need to see clearly. Often enough, calling something a mystery simply means that we are, at the moment, ignorant of its cause; we don't have the necessary information. Others are assumed to have this information: experts, police, doctors, politicians, and the like. But are things so coherent? Here, too, Proust has much to tell us:

I had seen everybody believe, during the Dreyfus affair or during the war, and in medicine too, that truth is a particular piece of knowledge which cabinet ministers and doctors possess, a Yes or No which requires no interpretation, thanks to the possession of which men in power

knew

whether Dreyfus was guilty or not and

knew . . .

whether Sarrail in Salonika had or had not the resources to launch an offensive at the same time as the Russians, in the same way that an X ray photograph is supposed to indicate without any need for interpretation the exact nature of a patient's disease. (III, 953)

In linking together the inscrutability of politics and history and medicine, Proust suggests that there are no keys, no secrets, no bottom line; or rather, that there is endless signifying, that the key to the puzzle is another puzzle, that the X ray is just another document, a construct that can be put together variously and deciphered variously. Kafka, in reflecting over his own tuberculosis and the riddle of its etiology, put it this way: "The origin of tuberculosis is no more to be found in the lungs, for example, than the cause of the World War is to be found in the Ultimatum. There is only one sickness, no more, and medicine blindly chases this sickness like an animal through endless forests" (1958,320).

Kafka's focus on the blind chase, like the Proustian scrutiny of the X ray, speaks clearly, I think, to our urgent desire to know, to have light and clarity in crucial areas of life, both public and private, somatic and cerebral. "Blind chase" expresses nicely the central plot of most lives: a

trajectory at once "driven" and in the dark. To put it that way is to acknowledge just how benighted our basic circumstances actually are: we cannot see inside our bodies, we cannot read others' minds, and we are a bit fuzzy about other things too, such as what is really going on in the world around us. Much is closed to human perception: dogs hear and smell better, pigs find truffles, and, in a novel obsessed with reading land and body and mind, Faulkner's

As I Lay Dying,

the mules standing at the floodwaters are not so different from Tiresias, clairvoyant but mute rather than blind: "looking back once, their gaze sweeps across us with in their eyes a wild, sad, profound and despairing quality as though they had already seen in the thick water the shape of the disaster which they could not speak and we could not see" (139). Thus, we live, and have lived, among clairvoyants and prophets and visionaries, ranging from the oracles and soothsayers and medicine men of old to our contemporary meteorologists and economists and other witch doctors who are there to read the present and the future, to interpret the signs, whether it be a low-pressure system or a cholesterol count or the NASDAQ Index.

GETTING IT WRONG

Once we consider how much guesswork as well as science is packed into the diagnostic project, it can hardly surprise us that doctors—as well as meteorologists and economists—sometimes get it wrong. For this reason it may be worth remembering what kind of figure the doctor cut in the comic literature of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Here we find stories of hilarious misdiagnosis. Moliere poked fun at doctors in no fewer than five of his plays, partly because he detested doctors, partly because he knew all too well the power they acquire over the sick, and he could rely on gut laughter from his audience merely by putting the Latin-spouting doctor onstage; how could this fool get

it

right?

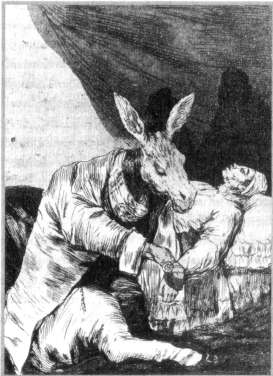

Los Caprichos,

plate 40, "De que mal moira?," Francisco de Goya y Lucientes.

Who among us has not sometimes experienced the unpleasant suspicion that the doctor doesn't get it, understands nothing about what one is really suffering from? Goya's painting of a donkey-doctor may be a step further than most of us would go in our anger and dismay, but this evocation registers with rare vehemence just how botched these matters can become. The man trained to decode and minister to our

soma

is himself a crude beast, devoid of diagnostic acumen, pictured almost vampirishly athwart the patient's chest, crushing the poor victim, mocking all scientific pretensions with the jackass ears reflected on the wall.

What are the causes of faulty diagnosis? From a scientific perspective, we'd have to say "insufficient data" or perhaps "skewed assessment." But might the explanation be of a different sort altogether? The literary version of these matters can be, as it were,

environmental,

allowing us to grasp the diagnostic encounter as a cultural event, filled with epistemological challenges, yes, but not necessarily of the sort learned in medical school.

One of the most virulent examples of wrongheaded diagnosis is to be found in Charlotte Perkins Gilman's classic story of 1892, "The Yellow Wallpaper," in which the husband/doctor cheerfully forbids his ailing wife any form of mental or physical activity—no reading, no writing—whatsoever. Gilman herself, in the wake of a depression, had consulted the famous neurologist S. Weir Mitchell, and undergone his "rest cure," which almost drove her mad. She wrote this story in response to this experience, and wrote it from the angle of vision of the suffering wife. Today it is easy to see in the infantilizing behavior of the husband an attitude toward women that derives from nineteenth-century notions

of hysteria,

as they were articulated by the male medical establishment. Thus, we understand his various prohibitions for his patient as so many (unwitting?) patriarchal judgment calls, enabling us to see how much cultural conditioning might be invisibly packaged into doctors' interpretations and injunctions.

Another, still more famous story about male doctors getting it wrong is Hemingway's very early piece "Indian Camp," where the young Nick Adams accompanies his doctor/fadier and his uncle as they go by row-boat (traversing a distance that is greater than they realize) to attend an Indian woman with a difficult labor. Much of the story's power derives from the "innocent" angle of vision, an innocence that the reader only gradually evaluates; here is what they see upon entering the shanty:

Inside on a wooden bunk lay a young Indian woman. She had been trying to have her baby for two days. All the old women in the camp had been helping her. The men had moved off up the road to sit in

the dark and smoke out of range of the noise she made. She screamed just as Nick and the two Indians followed his father and Uncle George into the shanty. She lay in the lower bunk, very big under the quilt. Her head was turned to one side. In the upper bunk was her husband. He had cut his foot very badly with an ax three days before. He was smoking a pipe. The room smelled very bad. (16)

Nick's father explains to him that this woman is going to have a baby, and he goes on to clarify why she is screaming, and what it means: "What she is going through is called being in labor. The baby wants to be born and she wants it to be born. All her muscles are trying to get the baby born. That is what is happening when she screams" (16). The screams continue, and Nick asks if his father cannot give her something to stop it, and the doctor replies that "her screams are not important. I don't hear them because they are not important" (16). The doctor then performs an emergency cesarean for this difficult breech delivery (which Nick queasily watches), and he is feeling understandably upbeat at its successful conclusion: " 'That's one for the medical journal, George,' he said. 'Doing a Caesarian with a jack-knife and sewing it up with nine-foot, tapered gut leaders' " (18). It is only then that they realize there has been no reaction from the "proud father," and upon examination they discover that he has slit his throat from ear to ear with an open razor.

For years I have taught this story as an instance of medical obtuse-ness, of a doctor who tragically underestimates the significance of pain and screaming, since we must assume that the

husband

simply could not bear it any longer. The doctor's repeated assertion, "her screams are not important," is fatally wrong, and here would be a textbook example of how a scream goes (indeed) through the house. In recent years, however, students have helped me to see this story more "environmentally": the white men from across the water enter the Indian shanty and proceed to do their medical tricks, and we can only wonder what such a spectacle looks like to the woman or her husband.

And it may be that there is also a virulent gender fable on show here: the white male doctor cuts open the Indian woman's body—she can show her resistance only through biting, is called "damn squaw bitch" in return—and we are left to ponder how much murderous horror this might have for the Indian couple. The story closes with Nick, his father, and his uncle making their way back across the water, but readers of Hemingway are entitled to feel that there is no closure whatsoever, in that Hemingway's own doctor/father was to commit suicide many years later, just as Ernest himself would in 1961, leaving us with the eerie feeling that this story was to be dreadfully prophetic in its depiction of pain as something unbearable after all.

"That's one for the medical journal," was the doctor's smug conclusion in finishing his handiwork. On the contrary, as a piece of literature, Hemingway's pithy story urges us to rethink our medical journals, to widen our optic when we take the measure of the challenge(s) at hand. These literary and artistic representations of botched medicine and skewed assessments, from Moliere to Hemingway, are themselves tough medicine for readers who seek help, for we all depend on the doctor's scientific gaze. Yet, we see ever more clearly how fraught with libidinal or ideological blinders that gaze might be.

Surely, the supreme literary instance of the doctor's gaze being clouded—usurped—by unacknowledged libidinal forces is Kafka's surreal story "A Country Doctor." The piece begins with a dilemma: the doctor has to get to a patient ten miles away, but he has no horses in his stable; then, as if by magic, two powerful horses "buttock" their way out of the pigsty, followed by a (never before seen) groom who promptly sinks his teeth into the cheek of the doctor's maid, Rosa. The doctor takes off for his patient, intuiting with perfect clarity that the cost of these miraculous horses will be the rape of Rosa. He reaches the sick child, whom he initially diagnoses as not sick at all, but then changes his mind when he sees a blood-soaked towel and discovers a wound that seems off the charts: