Arnold Weinstein - A Scream Goes Through The House (31 page)

Read Arnold Weinstein - A Scream Goes Through The House Online

Authors: What Literature Teaches Us About Life [HTML]

Locked Up,

Lena Cronqvist, 1971.

that could have been imagined by Foucault in his discussion of the Panopticon (in

Discipline and Punish)

and the surveillance strategies used by the State to discipline its subjects.

Cronqvist did an entire suite of paintings about her stint at St. Jor-gens, all of them testimony to the estrangement and dehumanizing experience she underwent, but I'd like to focus on an apparendy more benign piece from the series,

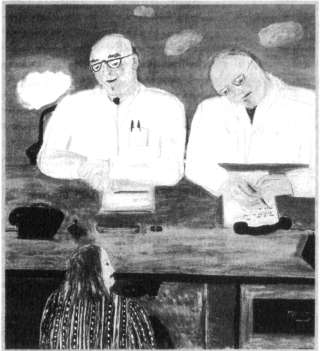

Private Conversation.

This painting utilizes the same vertical perspective to denote the key pecking order that reigns in hospitals: the sick subject at the bottom, face looking up with trepidation, then the massive table presided over by the two physicians.

Private Conversation,

Lena Cronqvist, 1971.

The one on the left looks down at her with the kindness you'd bestow on a lesser specimen, while the one on the right records his findings on the sheet of paper in front of him, likely to produce a document that will be filed precisely in the closed drawer we see on the right.

Against a remarkable backdrop of sky and clouds (where are they? could the patient possibly escape out there if she could get past the doctors?), we nonetheless note the insistent clinical setting, most brilliantly emphasized by the two telephones that are prominently on display.

Private Conversation

is the Swedish title, but there is also a connotation of "Private Confession," implying something on the order of a religious confession, but the telephones (one of which is off the hook) announce just how impeded, "long-distance," and mechanical this consultation

actually is. The telephones, the note taking, the complacent professionalism of the two doctors, all speak of the failure of any genuine communication, as well as the imposition of a hierarchical, imprisoning order in which her anguish, although unheard and unalleviated by the doctors' ministrations, keeps her nonetheless imprisoned in the system.

THE VIEW FROM THE PRISON

With Cronqvist's depictions we encounter how the coerced female subject might feel, and there is nothing easy to interpret about it. Cronqvist delivers an image of her prison and her captors that resists easy classifying: tragic? sardonic? mad? But this situation can be imploded still further, inasmuch as narrative might provide a vehicle for rendering the victim's vision that is even more capacious than painting.

Hence, I want to return to Charlotte Perkins Gilman's story "The Yellow Wallpaper," since it provides perhaps our classic depiction of the "colonized" vision. Less noticed, however, is the amazing reversal of power that is staged in this harrowing story, as if, through storytelling from the victim's side, you could show how the institutional bullying that such arrangements routinely conceal—John thinks of himself as loving husband, solicitous physician—might be spectacularly reversed.

Gilman's speaker, denied pen by her husband, nonetheless recounts for her readers her harrowing and hallucinatory descent into madness, as she interacts ever more obsessively with the putative figures depicted in the pattern of the wallpaper of the "nursery" room where she is virtually incarcerated (not for nothing are the windows barred and the floor scratched and gouged and splintered and the bed nailed down). Gilman's story is most remembered for the narrator's fascinating account of the insidious wallpaper: it has curves and flourishes, is figured as "waves of optic horror" and "wallowing seaweeds," resembles toadstools "budding and sprouting in endless convolutions," sports "two bulbous eyes," smells foul.

This imagery seems to signal some sort of fetal fantasia, a landscape

of pure (and obscene) spawning that is unbearable. Soon enough, the pattern yields its human figure, that of a trapped woman trying to break through the wallpaper's armature, and this trapped woman then becomes an army of imprisoned women wanting out, "sisters" of sorts to the protagonist who blends with them, perhaps invents them as versions of herself and her plight. Ideological commentary on this story is pale and arid in contrast to the pathos and vibrancy of Gilman's own fable of sisterhood; at one point, the narrator leaps out of bed to help the trapped woman in the paper make her way free, yielding an ecstatic union of subject and vision, of hounded prisoner and emerging escapee: "I pulled and she shook, I shook and she pulled, and before morning we had peeled off yards of that paper" (47).

Gilman was a prolific author, one of the best-known female intellectuals in America at the end of the nineteenth century. The bulk of her fame rested on ambitious treatises about women and economics, about radically reconceiving the family and its domestic trap for women; the other fictions she wrote strike us as didactic. But "The Yellow Wallpaper" is unmatched in its mix of horror, immediacy, and economy, and there is something truly brilliant about a woman trapped in the pattern of wallpaper, for it is a resonant image of societal coercion, of the human subject as incarcerated within the very

design

of patriarchal culture. The story ends with the narrator's final entry/exit through the looking glass, into what we'd probably call madness, but a madness figured as triumphant exit from the patriarchal penal system in which she has lived.

What has gone uncommented on is the fascinating tug-of-war staged within the text, as the female protagonist not only asserts her own personal vision, but does so in wonderfully medical ways:

she

becomes the text's doctor figure, the wily diagnostician who observes her husband, "watches developments," soon finds John "so queer now," and finally becomes suspicious of his prying questions, "As if I couldn't see through him!" True enough, this woman ends up exiting the workaday world, joins the "creeping" women who live in and come out of the wallpaper. Yet, how telling it is that she simultaneously usurps the doc-

tor's position, reverses in some crucial way the power dynamics of the story, makes spectacularly visible to her readers the

huis clos

that her role as wife/hysteric has thrown her into, from which only her empowered, horribly liberated subjectivity can free her. She exits the doctor's prison as mad doctor.

There are simply no terms for assessing the value of this transformation. If self-assertion and agency can go nowhere other than into madness, then we have a Pyrrhic victory indeed. But it is a sign of Gilman's genius that the diagnostic war can shift gears, that the object can become subject by dint of her vision and also of her rigorous observation of the doctor in the house. The dynamic at work here resists easy labels-feminists are divided as to whether this outcome is triumphant or tragic—yet one is grateful for this exploratory fiction that does homage to the explosive shaping power of thought and imagination, most vital when most coerced.

Charlotte Gilman's cautionary fable is a drastic example of analysis run wild, analysis exposed as both ideological terrorism (the doctor's trap) and oneiric outing (the patient's exit). Gilman's woman finds freedom and solidarity in her madness, yielding a visionary richness that

only literature

can articulate. After all, what would

you

have seen, with only your eyes to assist you, had you entered the room with the yellow wallpaper? A woman on the floor? a woman gazing at the paper? a woman shaking and pulling? Or perhaps just a woman locked into herself?

Consider

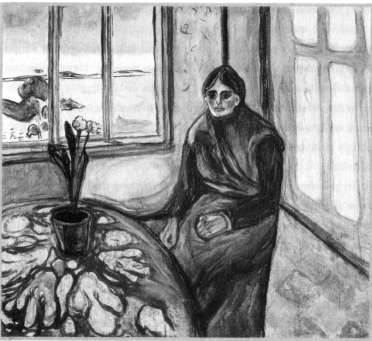

Melancholy,

Edvard Munch's portrait of his insane sister Laura, painted in 1899. Munch, with all the sympathy and love he can muster, cannot find his way into Laura's mind, cannot show us something rich and strange. What he can do is to articulate her imprisonment in multiple fashion: she sits dead still, hunched over; her eyes seem vacant and inner directed; the reflection of the wall repeats her incarceration; the vivid coloration of the tablecloth (some have compared it to raw meat) contrasts gruesomely with the deadness of the captive. This painting is almost a symphony of lostness, entrapment. This may be

Melancholy (Laura),

Edvard Munch, 1899.

why Gilman's deranged woman, no matter how wrecked we know her future to be, enacts a weird triumph of agency and doing, of actualizing her inner world. The madwoman completes her exodus by literally stepping on her husband. Seeing the prostrate doctor lying flat on the floor evokes this response from his "free at last" wife: "Now why should that man have fainted? But he did, and right across my path by the wall, so that I had to creep over him every time!" (50). My students want to cheer at that last line. Here, at last, the doctor gets his comeuppance.

THE DOCTOR: DIAGNOSTIC BULLY OR CRUCIFIED VICTIM?

In some instances, however, one feels that an artist has gone far out of his way to lay low the physician. I cannot imagine a more gripping example

of how the prestige of physicians (located both in their social station and in their wise, analytic prowess) can be blasted than by what we see in Ingmar Bergman's painful and punitive film

Wild Strawberries,

which sets out to expose the deceit and sham of an eminent doctor's life and career. Bergman is following in the footsteps of Hawthorne and Buch-ner in his indictment of coldness of heart, even though the indictment seems severe, sometimes unbearable, because the old physician is so lovingly and seductively depicted by the great actor/director Victor Sjostrom.

Bergman's doctor is spared nothing: we witness the nightmare scene where the doctor fails his medical exam, cannot translate the medical formulas, cannot see that the dead corpse is alive and jeering; the sadistic piece de resistance is provided by the examiner who briskly moves from botched test to a full-scale replay of the doctor's wife's infidelity, enacted in front of him once again in all its virulence, but now explicitly attributable to the doctor's emotional sterility and intellectual arrogance. The film's Dr. Borg has forgotten medicine's first commandment (according to the Swedish filmmaker): "A doctor's first duty

is to ask forgiveness."

Bergman's brilliant use of flashback and dream sequence displays something of the capacious logic at work here: the successful and omnipotent doctor may have fooled us all these years (in this case, he is en route toward a lifetime's recognition, in the form of a prestigious honorary degree), but the demons will out, the comeuppance will arrive, and it will be unstoppable.

Bergman's cruel vivisection of Dr. Borg has some intriguing parallels with one of Sherwood Anderson's doctor portraits in

Winesburg, Ohio.

The murky story "The Philosopher" focuses on Doctor Parcival, man with a secret, whom Anderson presents as a dark riddle of self-loathing and transgression, yet striving for some kind of utterance. The story is larded with deaths and images of filth and blood, and at a key moment the doctor announces his oracular tidings: "It is this—that everyone in the world is Christ and that they are all crucified."

This tortured story registers the cost of doctoring, the unwashable

dirt that is the residue of living with illness and death, that comes from medicine's failure to stop either of these two routine natural disasters. (We know, from the medical literature, that doctors have a significant incidence of psychological disorders, that they are subjected to quotidian levels of stress that are not easily managed.) Anderson's story does not slap around the doctor, as Bergman's film does, but it writes large the mesh of suffering, filth, failure, and blood in which doctoring is caught up. When

we

have performed our diagnostic task—to read this story's odd signs, to see the connection between blood-colored fingers, eyes red from soap-rubbing, unavowable secrets, unstoppable deaths—then we can, I think, assent to its view of crucifixion as the station of doctors.

DIAGNOSIS AND LOVE

The man who was crucified was also a doctor. The New Testament is larded with images of Jesus the physician, Jesus the healer who removes maladies and evil spirits from the bodies of those he meets. The lepers are healed, the bleeding stops, the blind become sighted.