Arnold Weinstein - A Scream Goes Through The House (43 page)

Read Arnold Weinstein - A Scream Goes Through The House Online

Authors: What Literature Teaches Us About Life [HTML]

But for the most part plague betokens an injury that is collective. This is why Tarrou's impassioned protest against complicity with murder and assassination rings true in this book, points to its ultimate concerns, its truest fears. All of Camus's tenderness is visible in the book's eloquent closing lines, as Rieux observes the gaiety and madcap happiness of the city now recovered from plague and realizes that such joy is always precarious, always threatened:

He knew what those jubilant crowds did not know but could have learned from books: that the plague bacillus never dies or disappears for good; that it can lie dormant for years and years in furniture and linen-chests; that it bides its time in bedrooms, cellars, trunks and bookshelves; and that perhaps the day would come again when, for the bane and the enlightening of men, it would rouse up its rats again and send them forth to die in a happy city. (308)

This beautiful closing passage tells us that plague cannot be exterminated. The extermination of men, women, and children, the destruction of happy cities, seems coded in the very genes of human civilization, always ready to be reawakened. Plague's origins are to be found in our homes and hearts as much as in our laboratories and slums. Books, the writer claims, teach us this. Camus's own book was published in 1947, and he died in i960, but the latter half of the twentieth century gives ample evidence of his prophecy. Collective mania and infection punctuate modern history, and the sanctity of human flesh and happiness has been annihilated on a massive scale, over and over. Prague, Hanoi, Dubrovnik, Belgrade, Belfast, Baghdad, Grozny, Kabul, countless cities in Africa and the Third World decimated by AIDS and poverty, perhaps even pockets of the U.S.A.: many are the cities laid waste by the rats.

SEEING

PLAGUE: OPENING THE SEALS: INGMAR BERGMAN

Exactly a decade after Camus wrote his meditation on plague as a reflection on the recent horrors of World War II and the German Occupation of France, the filmmaker Ingmar Bergman moved into international prominence by dint of an unforgettable film,

The Seventh Seal.

Bergman, known until then as a maker of cultish Swedish films, had been pondering the theme of this gothic work for a number of years (had earlier written a theatrical script entitled

Wood-Painting,

which contains virtually the entire plot of the film). The Swedish director is no

less topical than the French novelist: if the Nazi phenomenon was Camus's immediate symbolic backdrop, the specter of nuclear holocaust—a specter increasingly occupying people's fears in the 1950s— was Bergman's subtext. How, Bergman has to have asked himself, could you

show

to a complacent public what the end of the world looks like?

For Ingmar Bergman, son of a prominent pastor, there was an obvious verbal text at hand, the Book of Revelation, describing the famously sealed book of apocalypse. Bergman's gambit is clear: the film is to open up these seals. Hence,

The Seventh Seal

tackles no less than the ultimate, unsurvivable

revelation

that depicts world's end; at both the beginning and end of the film we hear the portentous words, the full script of which goes like this:

6. And when he had opened the seventh seal, there was silence in Heaven about the space of half an hour. (Rev. 8:1)

7. The first angel sounded, and there followed hail and fire mingled with blood, and they were cast upon the earth: and the third part of trees was burnt up, and all the green grass was burnt up. (Rev. 8:7)

8. And the second angel sounded, and as it were a great mountain burning with fire was cast into the sea: and the third part of the sea became blood. (Rev. 8:8)

9. And the third part of the creatures which were in the sea, and had life, died; and the third part of the ships were destroyed. (Rev. 8:9)

10. And the third angel sounded, and there fell a great star from heaven, burning as it were a lamp, and it fell upon the third part of the rivers, and upon the fountains of waters. (Rev. 8:10)

11. And the name of the star is called Wormwood: and the third part of the waters became wormwood; and many men died of the waters, because they were made bitter. (Rev. 8:11)

12. And the fourth angel sounded, and the third part of the sun was smitten, and the third part of the moon, and the third part of the

stars; so as the third part of them was darkened, and the day shone not for a third part of it, and the night likewise. (Rev. 8:12)

Here is your governing script, but it is not enough; you are producing a film, not a sermon. But ponder the central image: opening the seals. Bergman must have understood that this vital metaphor is no less than the ultimate truth of film itself: to

open up,

to make visible, the secrets of the world and the self. But this biblical story is still more evocative than that. One almost hears the "Eureka," hears the gears mesh, as Bergman ponders the insistent reference to destruction as

the third part,

and then realizes that this has already happened:

a third part of the world has been annihilated;

it happened during the Black Plague in the mid-fourteenth century.

This, Bergman knows, is visual. And he knows it has an iconography of great boldness and power because he has seen the pictures, seen them firsthand, when wandering around on his own in the medieval churches while his father preached (he used to accompany his father on pastoral duties). This is how Bergman remembered those images many years later:

Like all churchgoers at all times, I have often become lost in altar-pieces, crucifixes, stained glass windows and murals, where I could find Jesus and the robbers in blood and torment; Mary leaning on St John, woman behold thy son, behold thy mother. Mary Magdalene, the sinner. Who'd been the latest to fuck her? The Knight playing chess with Death. Death sawing down the Tree of Life, a terrified wretch wringing his hands at the top. Death leading the dance to the Dark Lands, wielding his scythe like a flag, the congregation capering in a long line and the jester bringing up the rear. The devil keeping the pot boiling, the sinners hurtling headlong into the depths and Adam and Eve discovering their nakedness. Some churches are like aquaria, not a bare patch. People everywhere, saints, prophets, angels, devils and demons all alive and flourishing. The here-and-

beyond billowing over walls and arches. Reality and imagination merged into robust myth-making. Sinner, behold thy labours, behold what awaits thee round the corner, behold the shadow behind thy back! (1988,274)

I cite this long passage from Bergman's autobiography as an index not only of his germinal vision for his film about apocalypse, but also as a piece of cultural history. American audiences came and come to this film with a sense of astonishment at its exoticism and strange folklore— I know, I saw this film when it first came to America, when I was an undergraduate; and I teach it every year to bewildered students—whereas these images were as old and familiar as mother's milk for baby Bergman.

It all comes together: the Book of Revelation, the biblical images in medieval churches, the Black Plague. To warn us of a future we cannot afford to experience—nuclear war—Bergman goes back to a past where one third of Europe perished. And his supreme concern is

visual:

how to show what this experience feels like? how to merge reality and imagination into "robust myth-making"? how to convey what it is like when "the here-and-beyond billows over walls and arches"? Bergman locates this obsession with

seeing

it squarely within the film itself, so that we have a key scene where the Knight and the Squire stop in a church and encounter a painter of murals, called appropriately

"lilla Pictor"

("little Pictor") after the famous Swedish muralist of the latter half of the fifteenth century, Albertus Pictus. Perched on a scaffolding, he explains to the Squire that his subject is "The Dance of Death," depicting the terror that plague brings, and he goes on to describe the body's fate: "You should see the boils on a diseased man's throat. You should see how his body shrivels up so that his legs look like knotted strings—like the man I've painted over there" (110). The Squire looks at the tortured figure, and the painter continues his lesson: "He tries to rip out the boil, he bites his hands, tears his veins open with his fingernails and his screams can be heard everywhere" (no). Standing in as a medieval version of

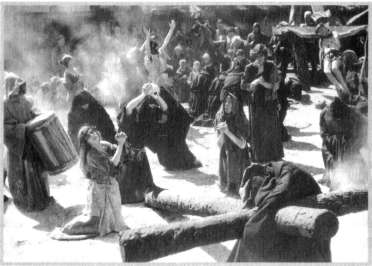

The flagellants.

Bergman himself, the church painter represents the filmmaker's project: to make people see graphically what plague is, to open the seals.

And that is what

The Seventh Seal

does. Plague is a time of torture: that meted out by the disease, and also that which we do to ourselves. Thus, Bergman treats us to the shocking procession of flagellants who whip their bodies in penance for their sins. No single still can convey the sense of mania and crazed behavior on view in this procession: their lips are gnawed and covered with foam, they bite and whip themselves, they sway and fall and jerk in such a way that the "Dance of Death" of the painter's vision seems horribly enacted here in the trancelike spasms of the living. To make certain that we understand their gruesome message, Bergman has them accompanied and led by the crazed monk who lashes out at the stupefied onlookers:

God has sentenced us to punishment. We shall all perish in the black death. You, standing there like gaping cattle, you who sit there

The monk's harangue.

in your glutted complacency, do you know that this may be your last hour? Death stands right behind you. I can see how his crown gleams in the sun. His scythe flashes as he raises it above your heads. Which one of you shall he strike first? You there, who stands staring like a goat, will your mouth be twisted into the last unfinished gasp before nightfall? And you, woman, who bloom with life and self-satisfaction, will you pale and become extinguished before the morning dawns? You back there, with your swollen nose and stupid grin, do you have another year left to dirty the earth with your refuse? Do you know, insensible fools, that you shall die today or tomorrow, or the next day, because all of you have been sen-

tenced? Do you hear what I say? Do you hear the word? You have been sentenced, sentenced! (124)

These brutal lines, taken from the film script, convey little of the searing and unhinging power that the actor Anders Ek endows them with in the film. His look of utter contempt and certainty as he harangues the crowd, his wailing and damning voice—I still hear his words, "your last hour" ("er

sista timme"),

turned into God's curse, "er SEESTA TEEEEMAH," or his scathing jeremiad against these stolid villagers, moving from one to the next, pointing the implacable finger of damnation at them, focused on their bodily pleasures and excesses—make all viewers (whether or not they know Swedish) feel the judgment at hand, a judgment that is being enacted in their flesh, so that pregnancy and laughter and defecation are all disgusting, nauseating signs of our corporeal shame, and the punishment is nigh. Here then is one of the oldest and most reliable interpretations of plague: God's judgment on sinners, God's (long overdue) punishment of the body and its carnal appetites.

Bergman is vitally interested in those

revelatory

dimensions of plague theorized by Artaud, the metamorphoses it produces in the bodies and the souls of those it threatens. Hence we encounter, early on in an abandoned farm, the renegade priest Raval, who now plies his trade by stealing jewels and valuables from the dead. Caught in the act by a young woman, he explains that these days stealing is quite lucrative, that the rules have changed: "Each of us has to save his own skin. It's as simple as that." He then moves on the girl (in good Artaud fashion) to rape her, still explaining: "Don't try to scream. There's no one around to hear you, neither God nor man" (116-117).