Arnold Weinstein - A Scream Goes Through The House (44 page)

Read Arnold Weinstein - A Scream Goes Through The House Online

Authors: What Literature Teaches Us About Life [HTML]

All contracts have been breached, it would seem, but this scene is being witnessed—people watching people watching people happens often in Bergman—by Jons the Squire, and he recognizes in Raval the source of still earlier rot, namely the (fraudulent) Crusades where he has just wasted ten years of his life: "Your name is Raval, from the theological

college at Roskilde. You are Dr. Mirabilis, Coelestis et Diabilis. . . . You were the one who, ten years ago, convinced my master of the necessity to join a better-class crusade to the Holy Land." Much of Bergman's tonality comes out in that word "better-class," signaling the ironic angle of vision that the Squire introduces into this film; played by Gunnar Bjornstrand, the Squire with his occasional bouts of sophisticated, street-smart, Stockholmese language, contrasts wonderfully with the Knight's (Max von Sydow's) existential, timeless, questing voice and manner. The Squire lets Raval off with a warning, "The next time we meet, I'll brand your face the way one does with thieves" (little knaves of your sort, the Swedish says). Sure enough, the Squire will meet Raval again, this time at an inn where he is torturing Jof, the film's lovable but helpless minstrel figure; and Jons keeps his word, takes out his knife, and slices Raval from forehead to cheek, effectively branding him. Raval is marked; his vicious soul

shows;

the spirit is imaged. Is this not one way of opening the seals: by rending the flesh?

Plague, as Artaud posited, heightens and accelerates these transformations and mutations. Bergman's camera focuses long and lovingly on the faces of his players, conveying the solid, material scheme that we inhabit (our bodies, our world). Yet this hitherto docile universe is drastically menaced by plague: the disease wrecks and deforms your body, the universe itself seems out of phase, amok. Thus, in the scene at the inn, the frightened villagers chronicle horrors: "They speak of the judgment day. And all these omens are terrible. Worms, chopped-off hands and other monstrosities began pouring out of an old woman, and down in the village another woman gave birth to a calf's head" (126-127).

Likewise, we learn that the priests have located the source of plague: "the woman carries it between her legs and that's why she must cleanse herself" (127). Old fears and fantasies are being rehearsed here, as they always are in times of plague, when

causes

must be found. The camera zooms in on these worried but decent faces, but it all changes when Raval starts to taunt Jof. The logic of scapegoating is heating up now, and we see with considerable clarity how "outsiders"—especially those

who are marginal and unprotected by law, such as actors and players— are viewed with suspicion, can be subject to outright torture. Raval forces the dazed, frightened Jof to dance on the table like a bear, and the camera again returns to the faces of the crowd, now laughing with sadistic pleasure, ready to see Jof tormented, indeed to see him die. Bergman does not flinch in his depiction of human hardness, of the transformation of an uneasy crowd into a lynch mob.

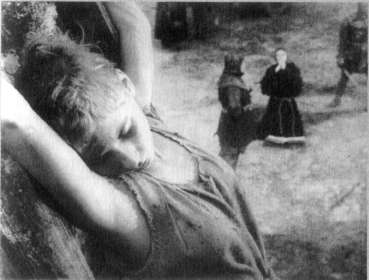

During plague, Raval can work up the villagers to violence. But in this matter of scapegoating and demonizing, Bergman reserves his real venom for the Church. Some of the film's starkest and most poignant scenes revolve around the ritual torture of Tyan, the girl-child who is branded a witch for confessing to carnal relations with the Devil. The soldiers have already shaved her head and broken her wrists, and they are going to burn her at the stake. Both the Knight and the Squire are moved by her plight, but unable to prevent her calvary. The Knight ultimately gives her a potion to deaden the pain, but his no less urgent goal is to interrogate her himself, to learn what she has seen, what secrets she may possess.

All of Bergman's interests coalesce here, as the drive for visibility, for opening the seals, becomes increasingly frantic. In answer to the Knight's urgent question about God's whereabouts, the girl asks him to look into her eyes, but all he sees is "an empty, numb fear." "No one, nothing, no one?" the girl pleads; "No," is the Knight's reply. As the flames mount, Jons is consumed with rage: "Look at her eyes, my lord. Her poor brain has just made a discovery. Emptiness under the moon" (148); It is not too much to say that "emptiness under the moon" ("

tomhet under manen")

is Bergman's core article of belief, and against that stark certainty we can gauge the cruel policies of the Church, but also the tragic absurdity of the Knight's quest, a quest that led him to the Holy Land and the Crusades, a quest now to see God in the time of plague. The killing of the girl Tyan is evidence of the sacrificial logic that Girard discerned in the

Oedipus,

and which I have discussed at some

The "witch" Tyan at the stake.

length as frantic communal narrative, as desperate desire to locate the miasma, the source of the disease.

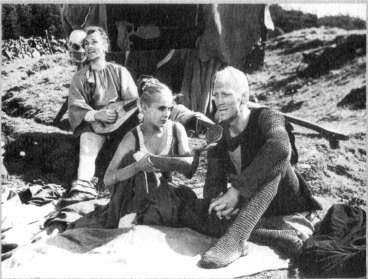

No moment in Bergman's entire cinematic oeuvre exposes the sham and cheat of questing and metaphysics as beautifully as the scene where Jof and Mia and Mikael offer the Knight and the Squire a bowl of wild strawberries and fresh milk. In the presence of a loving human family— unmistakably Bergman's version of the Holy Family—the Knight realizes the folly of his past life and the reality of this dense and rich human moment:

I shall remember this moment. The silence, the twilight, the bowls of strawberries and milk, your faces in the evening light. Mikael sleeping, Jof with his lyre. I'll try to remember what we talked about. I'll carry this memory between my hands as carefully as if it were a bowl filled to the brim with fresh milk.

(He turns his face

The "sacrament" of strawberries and milk.

away and looks out toward the sea and the colorless gray sky)

And it will be an adequate sign—it will be enough for me. (138)

Bergman rings a change on the Artaud formula of plague's dark explosions among human kind, because in this moment the Knight realizes that love and flesh are holy, just as the milk and the wild strawberries are unmistakably given to us as sacraments for the living, every bit as miraculous and transcendent in their way as the bread and the wine of the Eucharist.

"En stor tillracklighet,"

the Swedish says, "a great sufficiency," as if this dense moment of nurturance and intimacy

were, full,

not empty, were not a "sign" (as the English says), did not require "opening up." The world of living flesh and nature's bounty is transformed from closed seal to something radiant and shimmering. Human love alone fills up the "emptiness under the moon." Hence, this family will live, will be spared as plague visits Sweden. Whereas Defoe emphasized the social and emo-

tional horrors of infection, leading to a view of the enclosed family as guaranteed death trap, Bergman has posited human ties as alone enduring.

But plague is real. And Bergman wants to show it in ways that go beyond physical notation. Thus, even if wild strawberries and fresh milk are beautiful evidence of

this life's adequacy, The Seventh Seal

is nonetheless visionary, cued to a world beyond matter, from beginning to end. Jof himself is the film's seer, since it is he who is punished by others for his visions and fantasies, but the film is on his side, and thus all spectators endorse Jof's vision: we too see the epiphany of Mary and Jesus walking on the grass; just as we too see the specter of Death playing chess with the Knight, even if no one else in the film does. These moments of vision are accompanied by music, just as Mia's sweet affirmation of her love for Jof is accompanied by music. Spirit is real.

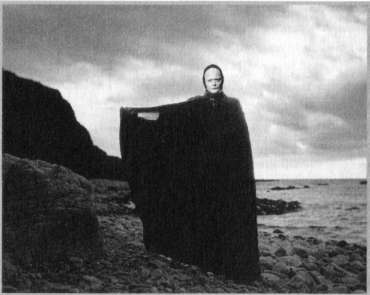

So too is Death. This film has an assured place in the history of film partly because of Bergman's audaciousness in actually putting Death on the screen as ghastly clown, Death as

visible presence,

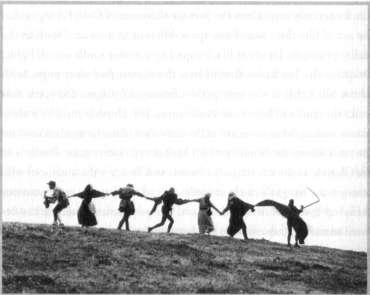

Death as chess player and fellow traveler. And although the religious framework of the film incessantly centralizes the presence/absence of God, I'd argue that the actual film does something quite different: it presents Death as the reality principle, Death as black-caped figure who snuffs out all lights, Death as the blackness that usurps the screen (see next page, top). Above all, death is the very personification of plague, the spirit that walks the land and lays waste to all human life. Death is the film's ubiquitous leading actor, as we see in the early shot of the ravaged cadaver on the road whom the Squire gets off his horse to interrogate. Death is in the Church, in the streets, in the forest. And Death is the great lord who besieges the Knight's castle at film's end, whose forcible entry into our sheltered lives cannot be halted, and whose ultimate triumph has become an unforgettable icon in film history: the Dance of Death. This too is, as it must be, a visionary moment that only Jof (and every viewer who has ever seen this film, and many educated people who have never seen this film) perceives:

above: Death opening his cape, below: The Dance of Death.

I see them, Mia! I see them! Over there against the dark, stormy sky. They are all there. The smith and Lisa and the knight and Raval and Jons and Skat. And Death, the severe master, invites them to dance. He tells them to hold each other's hands and then they must tread the dance in a long row. And first goes the master with his scythe and hourglass, but Skat dangles at the end with his lyre. They dance away from the dawn and it's a solemn dance toward the dark lands, while the rain washes their faces and cleans the salt of the tears from their cheeks. (163)

There is something utterly exquisite and utterly obscene here. The bodies with the boils, the burned witch, the ghastly flagellants, are now transformed into an image of transcendent beauty, stylized into the measures of dance and hieratic order. The seals have been opened. The medium of film registers, against the backdrop of mass terror and ubiquitous death, a luminous story about the human family in the time of plague, about death's reign and love's salvation: what began as a feisty and baroque bit of filmmaking, even as a warning about nuclear destruction, remains with us as a miracle of illumination.