Arnold Weinstein - A Scream Goes Through The House (53 page)

Read Arnold Weinstein - A Scream Goes Through The House Online

Authors: What Literature Teaches Us About Life [HTML]

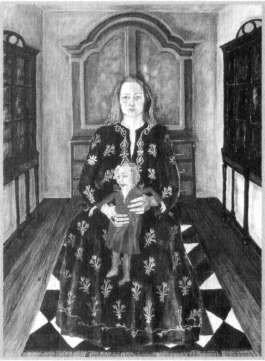

The Mother,

Lena Cronqvist, 1975.

eyes fixed on us and beyond, body poised and vital—is juxtaposed against the gigantic death-sculpture of the mother: death's head over life's head, death shriek against tight living lips, monolithic gray bulk against artist at the ready, hands prepared to create. Against a sterile backdrop of imprisoning planes, Cronqvist offers a mesmerizing story of mourning and creation, of currents that pass between mother and daughter, suggesting at once bondage, pain, love, and inspiration.

Cronqvist's most famous painting,

The Mother,

was done in 1975, well before the old woman's death, but it perhaps holds the key to our interpretation. In this lavish, ceremonial portrait of the artist, with its salute to grand Renaissance painting, we encounter the mother-daughter dyad in shockingly inverted form: the daughter holds the tiny

mother (kicking and screaming, one feels) over her womb, thereby signaling not only their link through sexual generation (albeit reversed) but, most crucially, the actual site of the mother. Mother is not yet dead, but the daughter carries her already, over her vagina, yes, but more generally as a parturition that can never take place. Contrary to the upbeat fable of integral and independent babies springing out of the earth (

The Midwife),

this painting advertises enmeshment and inscription as the reality of mothers and daughters, showingjust how imbricated we remain with and within one another throughout life. I cannot imagine a painting more in line with Proust's evocation of the grandmother's death, in that we see a moral and emotional geography that no photograph can render, a dispensation that graphs the actual human significance that others have for us. This painting overwhelms us with its imperious displacements, thereby exposing the Newtonian world of docile surfaces to be real enough when it comes to measuring rooms, but delusory when it comes to measuring relationships.

MAKING FRIENDS WITH DEATH

Most writers, great and less great, say death in their fashion, and no argument about literature's testimony in this area can pretend to any kind of adequacy or inclusiveness. The point, rather, is that literature, in being drawn to this grim topic, widens our optic, increases our store of knowledge, enriches our sense of futures. Terrible, awesome texts, such as

King Lear,

have a higher pragmatism in a culture that refuses to dwell on death, and Freud was not wrong when he claimed that Shakespeare's play was about the necessity of "making friends with death." This is no easy friendship. Lear himself does not manage it very well. Modern life seems especially allergic to talk of death, and many people in the United States talk cheerfully and confidently about the possibility of reversing aging, of extending life indefinitely, of getting yourself conveniently frozen until science has gotten its act together, at which time you would thaw out and resume action. The bodybuilding obsession and health

mania and wellness syndrome in popular thinking also suggest an unstated yearning for somatic immortality (soul is not very evident in much of this). Consistent with all of this, of course, is the fact that dying often takes place in special, closed-off precincts in modern industrialized cultures, hospitals and nursing homes, places where the old and infirm live together but that are off-limits to the young and healthy.

Needless to say, these truisms are balanced by a huge suspicion that death is real after all, and that our American way of handling it has much to be desired. The hospice movement is an effort toward bringing death back into a family framework. And the interest in alternative spiritual as well as medical traditions also indicates a reaction against "American death." That Sogyal Rinpoche's

Tibetan Book of Living and Dying

was something of a bestseller tells us that these matters still count, that our resolutely secular scheme is nonetheless death haunted.

My perspective on these matters is largely literary and imaginative, since I believe that it is in our imagination of death that we are most impoverished and shortchanged. But we all know that the socioeconomic dimensions of dying constitute one of America's great unaddressed problems. These issues, replete with actuarial tables and dollar assessments, are increasingly brought to the consciousness of older Americans by dint of the visibility given to such matters in public health policy as well as by the wake-up calls put forth by insurance companies and retirement plans concerning the need to put something away for those last, ghastly expensive years. In every sense of the term, we

pay

for our evasions. There is something economically obscene in the specter of entire estates being spent down, or outright ruined, in the (brief!) final stage of someone's life. I think that our engagement with death as a major conceptual "agenda item" deserves a wake-up call, and that the arts can be surprisingly vital here. It is time to realize that death and dying have a kind of imaginative and intellectual majesty and sweep that dwarf our current conversation about estate planning, long-term care, and even hospice arrangements.

If "talking" about death makes many people queasy, this is one good reason why it is useful to see just how prominently and profoundly death figures in literature from antiquity to our time. We will be better armed. I presented Proust's version of mourning as an amplification of what we learn in Freud and Kiibler-Ross, but it is obvious that we can go far back beyond Proust. The

Antigone

of Sophocles is entirely cued to issues of appropriate mourning and treatment of the dead, and all ancient cultures had complex rituals and belief systems in place for this final occurrence. We know all too well that these matters are hardly limited to a dispute as to which brother deserves burial rites; events ranging from airplane disasters to the plight of the "missing" and the "disappeared" in many political regimes to the Holocaust itself remind us that modern history is not only corpse ridden but also in search of appropriate forms of mourning and closure. Entire nations and geographical regions—Germany, the Balkans, parts of Africa and Asia and the Americas—have yet to make their way through these matters. It is questionable whether literature or any form of discourse can ever be fully commensurate with such drastic, open wounds, but one might argue that art does emerge from such crises. One remembers Claudel's definition of Greek tragedy as "

un cri devant une tombe ouverte"

("a cry in front of an open tomb").

THE VOICE FROM THE COFFIN

A modernist classic such as Faulkner's

As I Lay Dying

harks back to Sophocles in this area, focusing on the same scandal of rotting flesh that underwrites the tragic agon in the Greek text, and this twentieth-century novel sets out to give us an entire spectrum of possible views and attitudes toward the dying and dead mother, as instanced in the tortured mind-sets of her surviving family. But Faulkner, like Proust, knows that we can speak this event only as witnesses. One of the most remarkable sequences in his book is when Darl, the visionary son, attends to

the discourse of the coffin that contains Mother (a coffin that has been traveling for some days now, in intense Mississippi summer heat), and hears it actually make its utterance: "The breeze was setting up from the barn, so we put her under the apple tree, where the moonlight can dapple the apple tree upon the long slumbering flanks within which now and then she talks in little trickling bursts of secret and murmurous bubbling" (212). I can still remember the angry and shocked response of a student many years ago when I cited this Faulkner passage; this young woman had just lost a parent, and she found that my quotation was inhuman in its brutality. My (feeble) response was that Faulkner is seeking to register this brutality, that his book sets out to orchestrate forms of grieving, including the unhinged cry of the youngest child, Vardaman, who mixes up his horror of Mother in the coffin (won't she suffocate there?) with the memory of the bleeding fish in the pan served for dinner: "My mother is a fish."

When I return to the city where I grew up, I still go to the cemetery where my father is buried, and I look at that tombstone, trying to hear some voice coming out from it; often my mother was there at my side, and she had no trouble at all hearing his voice. I do hear it occasionally, on the other side of the country, mostly in my dreams, where this man long dead continues to live, but entirely according to "his own" schedule, so that I cannot summon him at will, so that I cannot even speak to him as I might, but rather as the dream dictates. And I wonder how I will inhabit the minds of my own children.

One of the ironies of modern culture is its peculiar treatment of high art. Either we subject it to the rigors of modern critical theory, so as to disclose the hidden ideological arrangements it contains; or we piously commit it to the scholar's care, with the implicit view that we "laypeo-ple" do not have the tools of access to frequent such work with any degree of profit. It would be better if we taught our students to view all art as fair game, to approach the most formidable and hermetic works as an aspiring thief might: with intent to break and enter, to discover, steal,

and possess what is there. Probably the most revered (and unap-proached) work along these lines—excluding, of course, Proust—is Joyce's

Ulysses,

a monument fit for adoration (from afar) or rejection (at once) or lifetime commitment (the scholar's view), but hardly a candidate for pilfering. (When is the last time you saw someone reading

Ulysses

on the bus or subway?) This is a pity because Joyce has a great deal to tell us about death, and we do not need special seminars or esoteric codes to make sense of it.

Ulysses,

it may be remembered, treats us to two memorable chapters in the early pages of the book—the later pages are something else entirely—about the responses of both Stephen Dedalus (the young artist) and Leopold Bloom (Joyce's adult "every-man" figure) to the phenomenon of death. Stephen will be haunted by the ghost of his dead mother (at whose deathbed he refused to pray), and in the sparkling "Proteus" chapter, we see him musing about the dialectic between "Godsbody" and "dogsbody," between the two rival narratives of death itself: either the transcendence of the soul that leaves its perishable carnal envelope, or the story of rot and putrefaction that living matter cannot escape. Joyce's rendition of Stephen's reflections is prodigiously agile and learned, ranging from inscriptions of the church to echoes of Shakespeare's "full fathom five" from

The Tempest

(this, too, a fable of magic "sea change" whereby bones become coral) to depictions of drowned and mutilated corpses.

Bloom—like Stephen, with his own private deaths still to mourn, that of his suicidal father and his son—rehearses these same issues in the "Hades" chapter. But Joyce is wonderfully naturalistic here, as his protagonist, truly a version of

l'homme moyen sensuel,

cashiers all fables of transcendence and paradise by focusing squarely on the somatic transaction at hand: the pump stops, is bunged, and you are dead; the rats make short work of you; any kind of "last judgment" whereby the dead rise and reassume their bodies is visualized as a grotesque vaudeville spectacle. Joyce is especially good at conflating the sonorous claims of the Church about mortality with the all too material fate of flesh:

Mr. Kernan said with solemnity:

—

I

am the resurrection and the life.

That touches a man's inmost heart.

—It does, Mr. Bloom said.

Your heart perhaps but what price the fellow in the six feet by two with his toes to the daisies? No touching that. Seat of the affections. Broken heart. A pump after all, pumping thousands of gallons of blood every day. One fine day it gets bunged up and there you are. Lots of them lying around here: lungs, hearts, livers. Old rusty pumps: damn the thing else. The resurrection and the life. Once you are dead you are dead. That last day idea. Knocking them all up out of their graves. Come forth, Lazarus! And he came fifth and lost the job. Get up! Last day! Then every fellow mousing around for his liver and his lights and the rest of his traps. Find damn all of himself that morning. (105-106)

There is something shocking but tonic, as well as hilarious—"come forth, Lazarus! And he came fifth and lost the job"—in this send-up of transcendence and its accompanying fables, and Bloom's suspicion of high rhetoric makes me think of Mark Twain's impatience with what he called "soul butter." But let no one think that such naturalism is reductive; after all, not every pump can manage thousands of gallons of blood every day, and Joyce returns unerringly to this plumbing later in the book, in "Ithaca," when he has Bloom open the faucet in his kitchen, followed by a mind-boggling paragraph that inventories the entire Dublin waterworks. Joyce, like any physician, is wise about the internal pipes and fluids that maintain life, but not many doctors are capable of his brilliant counterpoint. And mind you, Joycean music is possible even here, as, for instance, when Bloom imagines efforts to communicate with the dead as a kind of telephonic relay system that would "network" all corpses with their survivors. It sounds like this: "Have a gramophone in every grave or keep it in the house. After dinner on a Sunday. Put on poor old greatgrandfather Kraahraark! Hellohellohello amawfullyglad