Arnold Weinstein - A Scream Goes Through The House (52 page)

Read Arnold Weinstein - A Scream Goes Through The House Online

Authors: What Literature Teaches Us About Life [HTML]

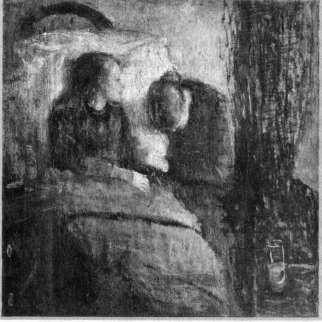

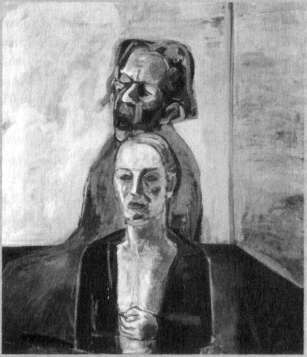

The Sick Child,

Edvard Munch, 1885.

MOURNING VISUALIZED: EDVARD MUNCH

I have wanted to take a leisurely tour through Proust because his treatment of death upends our truisms about finality and closure. I am tempted to say that he needs all those thousands of pages to get his job done, even though readers (and publishers) are understandably leery of fat tomes that come in multiple installments. Why are we in such a hurry? Why shouldn't art reflect something of the actual twisting and turning, the forgetting and remembering, indeed the living and dying that make up life. Perhaps this is why novels secretly lure us: between front and back cover they package time in such a way that we might retrieve it. Yet, as we saw in Munch's

Self-Portrait with Skeletal Arm,

painting may achieve similar ends. Susan Sontag argued long ago, in her

fine book

On Photography,

that photographs have an inherent aura of evanescence and mortality about them, and anyone who has ever owned or looked at a scrapbook knows something about this emotional truth.

Could the complexity of mourning be represented visually? Let me return to Munch, who seems an automatic reference here, as a kind of coda to Proust. The Norwegian painter has acknowledged, in his correspondence, how haunted he was, how powerfully the past shaped him and held on to him: "Disease, insanity and death were the angels which attended my cradle, and have since followed me throughout my life" (Munch, in Hodin, 11). It is no accident that Munch's breakthrough painting

The Sick Child,

done first in 1885 (and continually redone throughout his life), is devoted to the death of his sister Sophie a decade earlier. This early canvas, representing for some scholars Munch's "road not taken" (by dint of its impasto technique and scored surface, all so different from the famous "flat" style developed in the mid-nineties), has a rare emotional vibrancy. One feels that the very technique of the painting (scraping, scouring, gouging) expresses the physiological onslaught suffered by the consumptive Sophie, as if the painter wanted to show disease's inroads, to show how vulnerable skin can be. The face of the girl is serene, almost ecstatic, as she looks at and past the consoling, nurturing aunt (Munch's mother had already died of the same disease years earlier). We can feel the perspiration caused by fever, the weight of the wet hair, all leading to an almost ethereal image of Sophie, as if the crucible of disease had transfigured her, reduced her to pure spirit.

What has always moved me most in this painting, however, is the almost unbearable eloquence of the "mother-daughter" dyad, the older woman who looks down, who

knows

she cannot save the child. And yet, love endows this scene of dying with great beauty, for we see the human family as it is, two figures joined by tenderness and compassion, lending a rich "social" aura to the gloomy depiction of bed, patient, curtain, and medicine. Dying can be shared if not stopped. Munch has painted this scene some ten years after the event, and this calendar speaks volumes:

the painting

is

Munch's mourning, his way of showing that this scene cannot die, this doomed love still lives, this compassion is forever fresh. My terms are not so different from those on Keats's urn—"Forever wilt thou love, and she be fair"—for they point to the same miracle of art: it keeps feeling alive; it vanquishes death.

Munch seems to have been shackled to Sophie's death, so much so that one can scarcely avoid thinking that this obsession was strangely vital to him, acting as a catalyst for his art as much as his memory and love, so that we may now construe mourning to be, at least for this painter, generative. Consider the psychic economy on show here: fidelity to the dead sister is also a cunning pact with one's artistic mission. I find this attitude especially noteworthy when we contrast it with today's "now-cult," most vividly epitomized in that vulgar refrain that all of us hear when we are mired in thought or memory or remorse:

get on with it.

Munch's lifelong cultivation of his early (and later) traumas suggests pragmatism as much as morbidity, and causes us to rethink Freud's notion of the dead as dead tissue (and thus unavailable for cathexis).

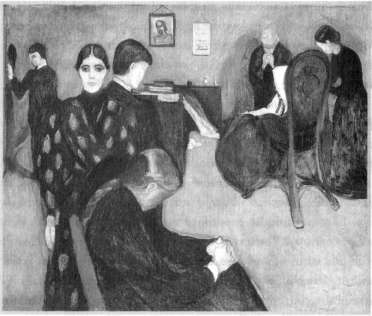

Nowhere is the astonishing fruitfulness of mourning/memory more visible than in the most famous canvas Munch devoted to Sophie's death, painted in 1895 (nineteen years after the fact),

Death in the Sickroom.

It is fair to say that this painting

gestated

in Munch, since the figures we see are depicted as young adults, not as the children they were at the time of this event. This painting advertises cohesion as much as separation and presents the family unit as umbilically linked, frozen hi-eratically at the moment when one of them is lost. The dying Sophie is seated, her back to us, in the chair, attended by the helpless father and aunt, but all the energy and power of the painting is lodged in the posture and experiences of the sibling witnesses, the children who experience

together

this death. The brother Andreas seeks to exit the scene and is caught (forever) at the door, in a posture of foiled escape (foiled by the painting itself) that Munch will return to in his later work. (One does not get away, Munch seems to be saying, one continues to live in, through, and via the deaths of the past.)

Death in the Sickroom,

Edvard Munch, 1895.

But the center of the piece is the astounding three-headed mass that registers Sophie's going: Inger, whose face looks like a frozen death mask, stares head-on at us, sphinx-like, defying us to make sense of what we are witnessing; Laura, head angled down with hands folded in resignation, inaccessible to our scrutiny; and Edvard, who has turned his gaze, Medusa-like, fully on the horror, taking in the moment of exit that he will then reproduce in the painting that we are looking at. I do not think these siblings are joined by compassion or sympathy; rather, they constitute a pictorial block, an indissoluble unit (a unit that includes Sophie), welded together by the experience of death. This collective fixation on the moment when one world is left and another entered constitutes a

rite de passage

in more ways than one: Sophie leaves the living, but Edvard becomes an artist. And it doesn't seem fanciful to say that Edvard's journey balances Sophie's, that his homage maintains her

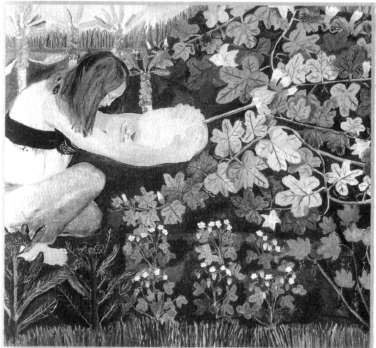

The Midwife,

Lena Cronqvist, 1972.

life. The stiff, hushed postures of the witnesses suffuse this portrayal of death with both mystery and majesty, causing us to feel the muffled force that is making its presence known in this family.

WATCHING THE DYING: LENA CRONQVIST

Munch and Proust have often been classified as neurotic, and in some areas, notably their depiction of erotic relations, the charge has merit; but I suggest that their respective fixations on death are ultimately fertile, seeding the art they produce.

Death is fertile.

We all know that our first birth comes from father's seed and mother's egg; in some inar-guable way, our "birth" as adults must derive from our parents' deaths, a kind of second seeding that we experience as trauma, but also as fate

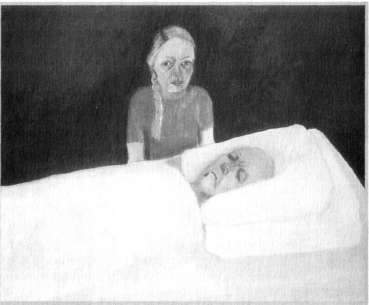

The Wake,

Lena Cronqvist, 1980.

and as launch. Artists offer precious testimony here, and I want to draw on the work of Swedish artist Lena Cronqvist to illustrate this point. In her series focusing on the death of her father and mother, we see a kind of narrative, or temporal, imagination that is capable of the same richness we saw in Proust. But let me start, for contrast's sake, with one of Cronqvist's most genial pieces,

The Midwife,

which resolutely treats birth as a natural, organic, indeed botanical event. The woman kneels piously in her garden and cradles the infant who has sprouted out of the earth. Generation seems removed from sexuality, and the production of babies acquires a serene, quasi-horticultural dimension, giving special meaning to our fond notion of babies as "nature's gift."

It is worth remembering this pagan, idyllic side of Cronqvist when we consider what happens at the other end of the spectrum, when father and mother die. The Edenic earlier setting has now become a darkened

Mamma and I,

Lena Cronqvist, 1987.

hospital, and in

The Wake,

we see the artist, with her robust flesh tones and red sweater, watching over a gray, horizontal father's corpse. It is interesting to note that this is a scene that Edvard Munch repeatedly depicted, always imagining and positioning himself as the supine corpse attended by the more or less spectral bystanders. Cronqvist clearly occupies the mourning slot here, the helpless onlooker who bears witness to death's hush and stilling of life. Only the father's head shows, but the painting conveys something of the sheer bulk of the dead, in terms at once physical and emotional, rendered somehow all the more palpable by the discreet white sheet. Nothing quite prepares us, however, for the searing series of paintings of 1986-88 entitled

Mamma.

Consider, for instance,

Mamma and I,

where daughter-artist—torso showing, bloodred