Atlantic (25 page)

Authors: Simon Winchester

4. THE SCAVENGERS OF THE SEA

Pirates—those who, as the law has it,

take a ship on the high seas from the possession or control of those lawfully entitled to it

—have created havoc in the world’s seas for as long as mankind has been sailing in them. Long enough to have passed firmly into folklore: the Jolly Roger, the eye patch, the parrot perched on the shoulder, the disfiguring scar, or perhaps a wooden leg, or a hook for a hand—and cruelly appropriate punishments like walking the plank—all these ingredients have created a fictional confection of pirates as somewhat capital fellows with a liking for bellying up to the bar. Only when one knows that a far more common piratical punishment was to gouge open a living captive’s stomach, drag out his entrails, and nail them to the ship’s mast, then force him to dance backward along the deck, running his guts out like a clothesline—does the romance begin to fade.

To be attacked by a pirate ship was a terrifying experience. The scenario had a certain routine to it: under the steady press of the westerlies the cargo vessel, laden with treasure or trade goods, would be lumbering heavily east through steady seas of warm aquamarine, minding her own business—when suddenly a suite of sails would appear on the horizon, and a small sloop would sweep swiftly into sight. At a distance it might be flying the flag of a friendly nation; when within sight or hailing distance, it would unfurl the plain black flag, or one adorned with skull and crossed bones (or cutlasses), that was the widely recognized pirate flag. The sloop would then would come alongside, its crewmen firing warning shots across the bows or into the sails and so ripping them to shreds, and would then tack wildly so that its own sails would begin to flap madly from the mast. The victim, slowed by its loss of sail power, would then be forced to lower her own ruined canvas and come to a dead stop. Grappling hooks would then be thrown, hawsers drawn taut, and as soon as bulwark smashed against bulwark, scores of heavily armed, wild-eyed young men would swarm over the rails.

The reality of seventeenth-century Atlantic piracy was often colored by the fanciful imaginings of artists, such as the creator of this nineteenth-century

wood engraving

. Most pirates were cruel beyond belief, took little pity on their victims, and enjoyed boisterous celebrations at sea.

They would be brandishing cutlasses and sabers and light axes that they would slash at anyone showing the slightest resistance or disapproval. Some of the pirates would round up the crew, begin interrogating them, beating them, stabbing, all too often eviscerating or strangling them—in one famous case nailing a sailor’s feet to the deck, whipping him with rattan canes, and then slicing his limbs off before throwing his carcass to the sharks. Others would rummage through the ship’s holds and through the cabins, searching for anything of value or of interest. There might be gold aboard; there would certainly be guns and powder; and maybe skilled crewmen who could be forced or persuaded to join the pirate ship. And then, perhaps mounting a final violent assault on the passengers by way of Parthian shot, they would all swarm back onto their own ship, detach the ropes, and slip rapidly away, soon passing over the horizon and leaving whoever remained of the crew and the surviving passengers to limp away for refuge and repairs.

The golden age for the pirates of the Atlantic—a term that in this context includes both the

buccaneers

of the Caribbean and the

privateers,

the fleets of state-sponsored brigands who attacked enemy ships on behalf of nations whose own ships were too busy elsewhere—lasted for no more than seventy-five years, from about 1650 to 1725. Thanks to writers like Robert Louis Stevenson and Daniel Defoe, the exploits of the most notorious found their way into the popular prints: men like

Blackbeard

—or Edward Teach—who conducted his business in the shallow waters off the Carolinas; or Captain Kidd and

Calico Jack

of the West Indies; or Bartholomew Roberts,

Black Bart,

whose beat was off West Africa; or Edward Morgan, who was pardoned of his early buccaneering and, as British privateering naval tactician of legendary skill and prescience, went on to be appointed a governor of Jamaica—all became celebrated, familiar figures. Writers had a heyday, too, with the small number of female pirates, most infamously Mary Read and Anne Bonny, who dressed as men and by chance encountered one another while serving on the same pirate ship—learning to their mutual dismay that each, of heterosexual inclination, was a woman.

Mary Read and Anne Bonny escaped capital punishment by declaring they were pregnant. Men had no such luxury: and as the naval patrols in the Atlantic and in the West Indies swept up more and more of their like, and as the world began to weary of their exploits, and as the scourge of piracy began to wear itself out, more and more men were brought home to England, many to suffer an especially appropriate execution.

Arrested pirates were tried in London in the Admiralty courts; and if found guilty, as most were, they were hanged on a special gibbet set up in the Thames at Wapping, on the muddy foreshore between the low- and high-tide marks. Captain Kidd was hanged in 1701 at this point, the so-called Execution Dock; the sentence handed down to him read, as was the custom, that his body must be left in the noose until three tides had passed over it and “you are dead, dead, dead.” Afterward the body was taken down, covered in tar to deflect the attention of seabirds, and hanged in chains at the mouth of the Thames at Tilbury. It was an advertisement, a warning to other mariners of the terrible sanctions that would be mounted against anyone planning to sail on a vessel that might unfurl the Jolly Roger.

The sanctions took their time—after all, there was so much money out there in the uninterrupted sea-lanes of the ocean. By the turn of the eighteenth century, however, a combination of policing by the Royal Navy and the rigid determination of the Admiralty courts conspired to begin to break the pirates’ grip. By 1725 the menace was ebbing away, and though it was not until 1830 that the very last pirates were hanged at the Execution Dock, the story of piracy in the Atlantic in the later eighteenth century steadily became more fanciful and romantic, and the reality of life on the ocean became more a matter of discipline, regulation, and the rule of law.

The British in particular enjoyed an early edge in suppressing the activity. But there was another evil that was very much more insidiously dreadful than piracy. By chance one of the more famous British piracy trials, and one not conducted at the Admiralty in London but in a corner of West Africa, shed some long-needed light on it. It was a curse of the high seas that was eventually to be among the most severely policed as well, such that in time it was finally abolished. Yet it was an extraordinarily long-lived maritime cargo-carrying phenomenon, the memory of which now scars and shames the world: the unseemly business of the transatlantic slave trade.

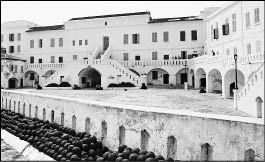

The Trial of Black Bart’s Men, as it came to be known, took place in 1722, in the dauntingly magnificent-looking, pure white cliff top building that still stands well to the west of the capital of Ghana: the famous Cape Coast Castle. It was adventurous Swedes who first built a wooden structure here, near a coastal village named Oguaa, as a center for gold, ivory, and lumber trading; it next passed into the hands of another unlikely Scandinavian colonizing power, the Danes; and then in 1664 it was captured by the British, who had an enduring colonial interest in West Africa and held on to the Gold Coast—as Ghana was then called—for the next three hundred years. At the beginning—and at the time of the piracy trial—the Castle became the regional headquarters of the Royal African Company of England, the private British company that was given “for a thousand years” a British government monopoly to trade in slaves over the entire 2,500-mile Atlantic coastline from the Sahara to Cape Town.

Though the monopoly ended in 1750, slavery endured for another sixty years and British colonial rule for another two hundred. The British turned the Castle into the imposing structure that remains today—and it has become sufficiently well known and well restored that it attracts large number of visitors, including many African-Americans who naturally have a particular interest in its story. The American president Barack Obama visited with his family in 2009, to see and experience what remains one of the world’s most poignant physical illustrations of the evils of slavery. The dire reputation of the place is reinforced by its appearance: though Cape Coast Castle is the smallest of the three surviving slaving forts on the Bight of Benin,

42

it was designed to be by far the most austere and forbidding. It also has the infamous “door of no return” through which tens of thousands of hapless African men, women, and children were led in chains and shackles onto the ships that then crossed the Atlantic’s infamous Middle Passage, eventually bringing those who survived the rigors of the journey to the overcrowded barracoons of eastern America and the Caribbean.

The trial, in which piracy and slavery overlapped in a way that intrigued the faraway British public, involved one of the Atlantic’s more notorious and commercially successful brigands, Bartholomew Roberts, a Welshman who was better known after his death as Black Bart. He had worked as third mate on a slave ship, the

Princess,

and in 1719 was lying off the Ghanaian coast when his vessel was attacked by two pirate sloops, captained by Welshmen also. A connection was duly made; Roberts joined one of the pirate crews and over the next three years captured and sacked no fewer than 470 merchant vessels—making him one of the most successful pirates in Atlantic history, and grudgingly admired even by his most implacable enemies.

Cape Coast Castle

was seized by the British and used as a central export hub for its West African slave trade. Like other former slave castles, with their infamous dungeons and doors of no return, Cape Coast Castle has become a place of pilgrimage for visiting statesmen, including President Barack Obama in 2009.

His luck ran out while he was careening his ships after a successful raid on a slaving convoy, once again off the Ghanaian coast. A Royal Navy antipiracy patrol, led by HMS

Swallow,

duped him into battle, and Roberts was fatally wounded in the neck by grapeshot. The 268 men on the three pirate sloops were taken away by the

Swallow

and her attendant vessels, and sent to the dungeons in Cape Coast Castle to await their sensational trial.

5. HUMANS, OFFERED WHOLESALE

Back in England, the men’s fate drew the most excited comments because among the captives were 187 white men, all alleged pirates, and seventy-seven black Africans, who had all been taken as booty from the captured slave ships. Of the white men, nineteen died of their battle wounds before the trial, fifty-four others were found guilty of piracy and were hanged from the cannons on the castle walls, twenty were sentenced to long prison terms in colonial African jails, and the remaining seventeen were sent back to London, to be detained in prisons there.

The seventy-seven black African slaves, innocent victims of all this mayhem, were not treated with any great leniency. They were returned to the Castle dungeons, were forced to walk once more in shackles and chains back through the door of no return, and were put on yet another slave ship and sent back across the Atlantic for a second time. This time they encountered no pirates and were delivered to the slave markets in the coastal cities, and became fully a part of the still-growing slave population of colonial America. A poetic injustice, if ever there was one.

And though many thinkers at the time recognized this, and though a tide of common opinion was beginning to turn, at the beginning of the eighteenth century there was still enormous official and intellectual support for the trade, in England and elsewhere. The better read of the slave traders were content to note that two thousand years before no less a figure than Aristotle had written of mankind that “from the hour of their birth, some are marked out for subjection, others for rule.” And even though some critics pointed out that the trade required that “one treat men of one’s own tribe as no more than animals,” still both the Church and the state accepted slavery as part and parcel of human behavior, part of the natural order of things. As an example: John Newton, an eighteenth-century clergymen of considerable piety—and talent: he composed, among other well-known pieces, the hymn “Amazing Grace”—was a slaver of some prominence and found no difficulty coming to terms with the fact that, as the

Dictionary of National Biography

has it, he was “praying above deck while his human cargo was in abject misery below.” Thus cleansed of any moral ambiguity, slaving could be an exceptionally profitable business.