Atlantic (29 page)

Authors: Simon Winchester

The

Battle of Jutland

, the greatest confrontation ever between two fleets of steel battleships—more than 250 enormous ships were engaged—started on May 31, 1916, and brought together the German High Seas Fleet and the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet. Twenty-five ships were lost and eight thousand men died, but the results, in strategic terms, were indecisive, with the Royal Navy still able to claim mastery of the eastern Atlantic.

The two fleets—the British Grand Fleet dispatched eastbound from Scapa Flow and the German High Seas Fleet steaming north from Wilhelmshaven, and each with battle-cruiser advance squadrons steaming before them—inflicted the most terrible punishment on one another, with ship after ship pummeled into submission by exploding shells, many sunk or exploded, and thousands of men killed in the most horrific circumstances. Two hundred and fifty steel ships fought with each other—twenty-eight British battleships, sixteen on the German side, and a huge number of auxiliaries. Both sides were astonished to lose capital ships that had been regarded—like the White Star liner

Titanic

four years before—as unsinkable and undefeatable. In the first hours of the battle, the British lost the

Queen Mary

and the

Indefatigable

, and later the

Invincible

, blown to smithereens when the flash from a German shell enveloped her magazine: all were immense battle cruisers. The Germans lost 62,000 tons of shipping during the two days of the conflict, and the British almost twice as much, 115,000 tons. Six thousand British sailors died, two thousand on the German side. Numerically it looked very much as though the Kaiser’s navy had won.

And all of this was in spite of the Royal Navy’s adroit success in crossing the German “T”—a performance of that classic naval maneuver that suddenly had German admirals seeing across their bows the entire Grand Fleet, with the British twelve- and fifteen-inch guns all trained to shoot broadsides that could decimate the Germans at will.

Yet the German fleet was not to be broken—a catalog of errors, signaling mistakes, poor gunnery, and bad ship design prevented the British from landing the knockout blow their commanders wanted. And despite all the carnage and loss, when the two fleets broke off the Jutland engagement and made it back home,

53

the cool reckoning suggested only one thing: that submarines, torpedoes, and aircraft would be the dominant ocean instruments of war for the remaining thirty months of fighting. Big-ticket naval engagements, in which admirals of the old school tried to impose Trafalgar-like battle tactics on the new world of high-technology navies, would be short-lived indeed. The great naval encounters of the next war, the Second World War, would largely be fought by aircraft from carriers. Two years later the entire German High Seas Fleet surrendered—thanks not to any direct consequence of the encounter at Jutland, but in essence because the war came to an end both as the result of an allied naval blockade of the German ports, which brought the Kaiser’s economy to its knees, and because the German army collapsed on the Western Front. The Kaiser’s ships were all interned in the Orkneys, behind the same booms of Scapa Flow from which the British Grand Fleet had sailed for Jutland. Seventy-four ships were imprisoned there after the 1918 armistice, with bored and humiliated German skeleton crews manning them, all their guns spiked, all their ammunition confiscated. All of them awaited the outcome of the slow-moving peace negotiations in Versailles.

But then on June 21, 1919, a prearranged secret radio signal, which in essence said simply “Paragraph Eleven—Confirm,” was flashed to all of the waiting German ships—and, obeying long-established emergency orders that would be implemented on receipt of this cryptic note, the captains of the anchored warships immediately scuttled every last one of their ships, by opening seacocks, smashing pipes, gouging holes in the hulls, and allowing fifty-two of the ships to slip slowly down into the shallow waters of the lagoon before the British—most of whose ships were away at sea on exercise—could stop them.

The British fumed—they had wanted to divide up the surrendered fleet among other navies—and did what they could to punish the miscreant German officers. But in the end the provisions of Versailles allowed the Germans to go home; and in time some of the larger vessels were raised and sold for scrap, the money going to the British Treasury. (Many of the hulls remain—and high-quality German steel salvaged from some of the remaining wrecks is occasionally brought to the surface today, much prized for certain very delicate scientific experiments, since it was fashioned, forged, and cut long before the spread of radioactive contamination, which has affected most metals that have been made since Hiroshima.)

Naval commanders may have learned as many tactical lessons from Jutland as their predecessors did from Trafalgar more than a century before, but these lessons paled when set against one reality that was little understood at the time but is all too well realized today. And that is that all naval fleets were from the late nineteenth century onward to be made almost entirely of steel—and Britain, despite the vastness of her imperial possessions and the industriousness of her people and the sophistication of her factories and foundries, had less steel than the Germans, and in just a few years the Americans would have much more than the Germans. In the future, whoever had the greatest access to high-quality steel would eventually have the wherewithal to build the greatest navy in the world—which the United States soon and most definitely managed to do. That, and the eventual deployment of different and infinitely more potent kinds of naval weaponry—and kinds of weaponry that were no longer exclusively wedded to traveling on the surface of the sea, but could weave their way beneath the water, or fly thousands of feet above it—was what Jutland has come to signal to the admirals of today.

It would perhaps be invidious to remark that just as the Great War had ended with a famous episode of German naval scuttling, so the Second World War began with another—a scuttling that also involved a German capital ship, and which also occurred in the Atlantic, although in this case the South Atlantic. The ship was the pocket battleship

Graf Spee

, and the event occurred outside the port of Montevideo in Uruguay, at the widest part of the mouth of the River Plate.

The ship, a sleekly villainous-looking Nazi surface raider, was part of Hitler’s plan to restore Germany’s navy to its former glory—but it had been built as a cruiser, since the Versailles Treaty prevented the Germans from constructing anything larger. She was very fast, and had been armed with an arsenal more suited to a battleship—including eleven-inch guns. She left Wilhelmshaven in August 1939. Her commander, a Captain Langsdorff, had sealed orders to attack all Allied-flagged civilian vessels in the Atlantic once war had been declared.

When the British prime minister made that formal declaration on September 3,

Graf Spee

had already broken out into the North Atlantic, steamed north of the Faroes, turned sharply south, and was well into the calms of the Sargasso Sea, a thousand miles west of the Cape Verde Islands. As soon as Germany was formally at war, Langsdorff ordered his guns unsheathed and began a rigorous program of commerce raiding, attacking every merchantman he came across.

Grain carriers, frozen meat carriers, fuel tankers, it made no difference—the

Graf Spee

went after everything she found in the South Atlantic, successfully notching up a kill every three or four days, causing major consternation up in London and paying no heed at all to the American zone of neutrality that President Franklin Roosevelt had established to protect Allied merchant ships sailing within a thousand miles of the shores of either North or South America.

But then, early in December, the deadly little battleship encountered three smaller Royal Navy vessels that had been ordered to scour the seas in a frantic hunt for her. They were the cruisers

Ajax

,

Exeter

, and

Achilles

, and when they met, and despite being massively outgunned and outranged, they joined battle with the German ship with the madcap enthusiasm and imprudent tenacity of terriers. It did not take long for

Exeter

to be so badly damaged that she was forced to retire, and although

Ajax

and

Achilles

suffered major damage, too, a lucky shell strike from

Exeter

’s eight-inch guns on the

Graf Spee

’s midsection hugely reduced her fuel-processing system, leaving her with limited fuel and (though no one except Langsdorff knew this at the time) a consequently doomed future. The stricken German ship slowly limped into the neutral safety of Uruguayan territorial waters, and up to an anchorage in Montevideo port—her officers knowing only too well that under the neutrality terms of the Hague Convention she had only seventy-two hours to effect repairs.

Huge public interest was aroused by the ship’s steadily ticking fate, particularly while British naval reinforcements were gathering—or were believed to be gathering: many clever ruses were being played—in the ocean beyond. It was gripping stuff. In London, Harold Nicolson, the politician and diarist, wrote as follows for his entry of the December 17:

After dinner we listen to the news. It is dramatic. The

Graf Spee

must either be interned or leave Montevideo by 9.30. The news is at 9. At about 9.10pm they put in a stop-press message to the effect that the

Graf Spee

is weighing anchor and has landed some 250 of her crew at Montevideo. As I type these words she may be steaming to destruction (for out there, it is 6.30, and still light). She may creep through territorial waters until darkness comes and make a dash. She may assault her waiting enemies. She may sink some of our ships. . . .

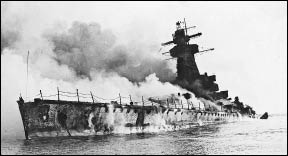

The

Graf Spee

did leave port just before the deadline—but she did none of things Nicolson imagined. She steamed slowly out across the territorial limit, trailed by a small tug. Then, four miles from shore and still within sight of the vast crowds on the Montevideo waterfront, her crews exploded three almighty demolition charges inside her. These set her furiously ablaze and, at risk of widespread public ignominy in Germany and Hitler’s private fury, they slowly and painfully sank her, in full view of the astonished mobs and to her equally astonished and relieved enemy. Captain Langsdorff, one of the more honorable of German naval officers at the time, was eventually taken off the burning ship, put in to port in Argentina, and two days later killed himself with a single shot to the head.

Burned and listing, the German commerce raider

Admiral

Graf Spee

sinks outside Montevideo harbor on December 17, 1939, after being scuttled by her crew. Neutral Uruguay demanded she leave port before she was fully seaworthy—prompting her captain to set demolition charges and send the pride of the Nazi fleet to the bottom.

For many years the wreck’s canted mast could still be seen poking above the muddy estuarine waters at low tide. One of the ship’s 150mm guns has been salvaged and is on display in a Montevideo museum, an anchor and a rangefinder are mounted on the foreshore, and the

Graf Spee

’s eagle crest was pulled from the water in 2006, its swastika covered with canvas to lessen any likely offense. Two cemeteries house the graves of those who died in the battle. But otherwise the burned and torn wreck of the ship remains untouched, marked on South Atlantic charts merely as a

hazard to shipping

—though somewhat less lethal a hazard today than she briefly had been in the southern spring of that first year of the war.

8. ENEMIES BELOW

Submarines were by far the greater hazard in the twentieth-century Atlantic, and during both of the conflicts. However, not at first: though they had been invented before the outbreak of the Great War—the world’s first was built in England in the seventeenth century; the first German submarine was made in 1850; the first German naval submarine in 1905—and though it was fairly obvious how these sinister boats could best be employed, as the unseen snipers of the ocean—the manner in which they were first used offered an almost courtly regard for the old-fashioned, gentlemanly values of seaborne warfare.

There had never been any doubt Germany would deploy its small but growing fleet of submarines as commerce raiders, using their torpedoes to sink as many of Britain’s supply ships crossing the Atlantic as possible. As an island nation, Britain could be supplied only by sea, and Germany’s actions were meant to wreck the British economy, starving her people and forcing her to subjection and surrender. But initially there were rules of engagement that had been laid down in treaties signed in Paris in 1856 and then again in The Hague in 1899 and 1907, and they related to what was known as Prize Warfare—the seizing or destruction of merchant ships on the high seas. These agreements all held, for example, that passenger ships should never be attacked; that the crews of merchant ships should be placed out of harm’s way before their vessel was plundered and sunk (and lifeboats were considered to be out of harm’s way only if they were within sight of shore—if out of sight of land the crews had to be taken aboard the attacking ship); and that formal warnings had to be given before an attack.