Atlantis Beneath the Ice (10 page)

Read Atlantis Beneath the Ice Online

Authors: Rand Flem-Ath

The prospect of navigating an unknown and overwhelming ocean was made a little less terrifying by dividing it into manageable sections (no matter how artificial), which could then be plotted on the explorers’ newly drawn maps. Soon the clamor for spices, silk, and other precious goods created a demand for even more detailed ocean charts. These maps reinforced the false concept of a divided sea and effectively erased the original

Greek meaning of the word

ocean

—a single body of water they called the Atlantic. Aristotle, Plato’s contemporary, described the Atlantic, stating, “This sea, which is outside our inhabited earth, and washes our region all round is called both ‘Atlantic’ and ‘the ocean.’”

10

To the Greeks the Atlantic lay to the north, south, east, and west of their world.

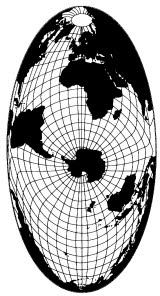

Our habitual view of the planet depicting north at the “top” of the globe reinforces the appearance of the ocean being separated into several bodies of water. However, oceanographers have long recognized that our planet has only one ocean—the “World Ocean.”

“The concept of the World Ocean held by a marine scientist is somewhat different from that of the layman. All of us learn in grade school to identify the names and placement of the continents and oceans. This exercise reveals that the oceans completely surround the landmass, but it is slightly misleading because it suggests that the oceans are separated geographically. From an oceanographer’s point of view, the emphasis should be on a world ocean that is completely intercommunicating.”

11

The unity of the single world ocean is obvious when the planet is viewed from the southern hemisphere (see

figure 4.3

).

Figure 4.3.

The world seen from the vantage of Antarctica as the center point highlights the unity of the earth’s single ocean. This map also reinterprets our notion of what constitutes a continent. Seen from Antarctica, the earth’s presumably separate continents can be seen to be parts of a single land mass. Source: U.S. Naval Support Force

Introduction to Antarctica

(Washington D.C.: U. S. Printing Office, 1969, centerpiece).

Sonchis described Atlantis as being beyond the known world of the Greeks in the “real ocean.” This “ocean truly named” matches the single world ocean of modern oceanography. The European-centered view dictated that the earth consisted of seven continents and an ocean blocked into a series of individual, smaller bodies of water: classifications that are unrelated to the earth’s actual geographic contours. The prejudices of European explorers became the world’s prejudices. Even the common divisions of east and west are only relative to Europe. But there is no

geographic

reason to place Europe in the center of the world. Our planet is quite democratically round.

So there is really only one world ocean rather than five separate oceans. Now let us consider whether there are really seven continents. Twelve thousand years ago a land bridge, Beringia, connected America to Asia. It was theoretically possible to walk through what today we call Europe, Africa, Asia, North America, and South America and never touch water. For the people of Atlantis these five “continents” formed the outer rim of their world: a “whole opposite continent” that

encircled

the world ocean.

Unlike our ancestors, who were forced to sail their way around the globe in patchwork fashion, we can see the entire planet through the all-encompassing eye of a satellite. Photographs from space reveal Europe as merely a peninsula of the Afro-Euro-Asian continent and North and South America as one continuous land mass separated only by the man-made Panama Canal. Treating North and South America as separate continents served the colonial interests of the kings and queens of Portugal, Spain, and England, not the science of geography. This dated perspective has blinded us to the location of Atlantis.

Sonchis attempted to explain to Solon the nature and location of Atlantis, but in order to give an accurate account he had to reach beyond the Greek’s limited notion of the globe. His description contains sixteen clues

12

to the site of the lost land.

- 9560 BCE

- Change in the path of the sun

- Worldwide earthquakes of extraordinary violence

- Overwhelming worldwide floods

- Island

- Continent (larger than Libya and Asia)

- High above sea level

- Numerous high mountains

- Impressive cliffs rising sharply from the ocean

- Other islands

- Abundant mineral resources

- Beyond the Pillars of Heracles (known world)

- In a distant point in the “Atlantic” ocean

- In the real ocean

- The Mediterranean Sea is only a bay of the real ocean

- The true continent completely surrounds the real ocean.

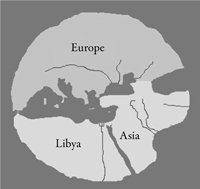

THE ANCIENT GREEK WORLDVIEW

The Greeks of Solon’s time saw the world as an island in the middle of a vast ocean. This world-island was divided into three important cultural units: Europe, Libya, and Asia.

The Pillars of Heracles were a psychological barrier, a forbidden gateway beyond which none but the foolish would dare to venture (see

figure 4.4

). The Greek poet Pindar (518–438 BCE) wrote that the Pillars were considered “the farthest limits [of the Greek world]. . . . What lies beyond cannot be trodden by the wise or unwise.”

13

This original concept of the phrase “Pillars of Heracles” is often forgotten or ignored by searchers for Atlantis, who assume only a literal interpretation of the phrase, thereby limiting the location of the lost continent to the North Atlantic.

What the Greeks called “Libya” described the area we know as North Africa. Their “Asia” was equivalent to the present-day Middle East. Only their “Europe” matched its contemporary area. In an encounter described by Plato 2,500 years ago, Sonchis told Solon that Atlantis was larger than Libya (North Africa) and Asia (the Middle East) combined—a match with the size of Antarctica.

Figure 4.4.

The Greek worldview at the time of Solon. The Straits of Gibraltar were then known to the ancient Greeks as the Pillars of Heracles.

Plato added that compared to the “real ocean,” the Mediterranean Sea is “but a bay having a narrow entrance.” In describing Atlantis, he stated, “To begin with the region as a whole was said to be high above the level of the sea, from which it rose precipitously . . . [and the mountains] were celebrated as being more numerous, higher, and more beautiful than any that exist today.

14

A description of Antarctica, published in 1992 (

more than twentyfour centuries later

), offers a strikingly similar geographic account. “The most conspicuous physical features of the continent are its high inland plateau (much of it over 10,000 ft.), the Transantarctic Mountains . . . and the mountainous Antarctica Peninsula and off-lying island. The continental shelf averages 20 miles in width (half the global mean and in places it is non-existent).”

15

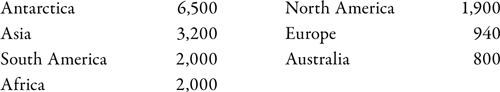

Like Atlantis, Antarctica rises high above sea level. Indeed, it is the highest continent in the world.

Average Elevation in Feet

16

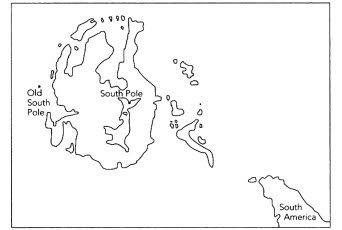

Figure 4.5.

Antarctica has a set of islands that are obscured by today’s ice sheet.

Geologists, using the theory of plate tectonics, have concluded that Antarctica was once joined to the mineral-rich lands of South Africa, Western Australia, and South America, and so they have reasoned that similar mineral resources must be locked beneath its frozen soil.

Two of the geological clues could only have been confirmed by modern science. In 1958 it was discovered that Antarctica, contrary to what we see on most modern maps, is not a monolithic landmass, but rather an island continent adjoined by a group of smaller islands not visible to the naked eye. Although these neighboring islands are covered by a fresh ice cap, seismic surveys have penetrated their blanket of snow to reveal the true shape of the island continent. An ice-free map of Antarctica unveils the “other islands” mentioned in Plato’s account (see

figure 4.5

).

THE ATLANTEAN WORLDVIEW

Ultimately, every search for the lost continent must answer to Plato’s detailed description of the island’s geography. When we step outside the comfort zone of our distorted cultural perception, Antarctica passes Plato’s test. Plato’s account provides an accurate, global view of the world as described to a Greek with a limited view of the earth. Although different

from our current perspective, it is accurate if we imagine ourselves residents of Antarctica. Atlantis is described to the Greek as being beyond his known world (Pillars of Heracles), and encircled by a vast body of water called the “real” ocean. Compared to the real ocean, the Mediterranean Sea is “but a bay having a narrow entrance.” The real ocean was the world ocean. Plato’s chronicle states that, when seen from Atlantis, the “real ocean” appeared to be framed by an unbroken mass of land that “may with the fullest truth and fitness be named a continent” (see figures

4.6

and

4.7

).

Figure 4.6.

These features of Plato’s Atlantis correspond directly with a worldview centered on Antarctica: a single world ocean, a surrounding whole opposite continent, some islands off Atlantis, the Mediterranean Sea is but a bay of the “real ocean,” and the size of “Libya” (North Africa) and “Asia” (the Middle East) approximates the actual size of Antarctica. Drawing by Rand Flem-Ath and Rose Flem-Ath.