Autobiography of Mark Twain (157 page)

Read Autobiography of Mark Twain Online

Authors: Mark Twain

381.9–10 “Adonis” (word illegible) acted] This musical burlesque starring comedian Henry E. Dixey was a record-setting Broadway hit, with more than six hundred performances from 1884 to 1886 (New York

Times:

“Amusements,” 5 Sept 1884, 4; “A Great Day for Dixey,” 8 Jan 1886, 1). The parenthetical comment was Clemens’s substitute for what appears to be “the pals”: “We went to the theater and enjoyed ‘Adonis,’ the pals acted very much” (OSC 1885–86, 17). Susy may have meant to write “the play acted.”

381.14 Major Pond] James B. Pond (1838–1903) was born in Allegany County, New York. First apprenticed to a printer, he became a journalist, and worked at several newspapers. During the Civil War he served in the Third Wisconsin Cavalry and was commissioned major at the end of the conflict. He joined the Boston Lyceum Bureau of lecture manager James Redpath, and bought out Redpath’s share of the business in 1875. Pond opened his own bureau in 1879. He managed Clemens’s 1884–85 tour of public readings with George Washington Cable, and arranged Clemens’s 1895–96 lecture trip around the world. Over the next years Pond made lavish offers for further tours, which Clemens declined (13 Sept 1897 to Rogers, 6–7 Nov 1898 to Rogers, 21 July 1900 to Rogers, Salm, in

HHR

, 300, 374, 448).

381

footnote

*I was his publisher] See “About General Grant’s Memoirs.”

382.14–18 General Hood . . . Sherman . . . was perfectly free to proceed . . . through Georgia] John B. Hood (1831–79) attended West Point, and served in the Union army until he resigned and joined the Confederacy in April 1861. He was promoted to major general in October 1862. Grant gave substantially the same account of Sherman’s march to the sea in his

Personal Memoirs

(Grant 1885–86, 2:374–76).

383.10–11 new and devilish invention—the thing called an Authors’ Reading] The event described here took place on Wednesday, 29 April 1885, at Madison Square Theatre, and was the second of two readings benefiting the American Copyright League. Clemens read his oftrepeated “A Trying Situation,” from chapter 25 of

A Tramp Abroad;

the other readers included Howells and Henry Ward Beecher. “Devilish” though he may have found them, the new fashion for authors’ readings (as opposed to recitations from memory) had been initiated by Clemens himself. The Washington

Post

noted that “the Cable Twain reading venture of last winter may be made the beginning of a new kind of entertainment. The lecture is obsolescent . . . but for an author . . . to read from his own writings is a new idea and an attractive one” (“News Notes in New York,” 3 May 1885, 5). Clemens’s Vassar lecture was on 1 May (

N&J3

, 112, 140–41 n. 48; “Listening to the Authors,” New York

Times

, 30 Apr 1885, 5; “Authors’ Readings,”

Life

5 [30 Apr 1885]: 248; “The Authors’ Readings,”

The Critic

, 2 May 1885, 210).

383.37–38 I went to Boston to help . . . memorial to Mr. Longfellow] The Longfellow Memorial Association was formed in 1882 to raise funds for a monument honoring the late poet. The authors’ reading benefiting the association was held at the Boston Museum (a theater) on 31 March 1887 (Longfellow Memorial Association 1882; “The Authors’ Readings in Boston,”

The Critic

, 9 Apr 1887, 177; see

MTHL

, 2:589–90 n. 1).

384.15 We got it arranged at last . . . fifteen minutes, perhaps] Howells read a selection from

Their Wedding Journey

(Howells 1872;

MTHL

, 2:589–90 n. 1).

384.18 I think that that was the occasion when we had sixteen] There were nine speakers at the Boston event (“Authors’ Readings for the Longfellow Memorial Fund,” printed program, CLjC).

384.18–20 If it wasn’t then it was in Washington, in 1888 . . . in the afternoon, in the Globe Theatre] Clemens was confusing two readings: the one in Boston, in 1887, and another in Washington, in March 1888, at the Congregational Church (not the Globe Theatre); see the note at 385.1–3.

384.24 That graceful and competent speaker, Professor Norton] Author and reformer Charles Eliot Norton (1827–1908) presided at the 1887 Boston reading. According to Howells, “he fell prey to one of those lapses of tact” when he introduced Clemens, claiming that Darwin habitually read his books at bedtime in order to feel “secure of a good night’s rest” (Howells 1910, 51).

384.27–33 Dr. Holmes recited . . . “The Last Leaf,” . . . until silence had taken the place of encores] According to a contemporary account, Holmes read only “The Chambered Nautilus” (1858) and “Dorothy Q.” (1871). Holmes “gave himself completely to the spirit of the

poetry, tingling and vibrating with life, rising on his toes and ending with a dash and sparkle which made his hearers beside themselves with delight” (“The Authors’ Readings in Boston,”

The Critic

, 9 Apr 1887, 177).

384.35–38 third place on the program . . . did my reading in the ten minutes] Clemens was first on the program, reading selections from “English as She Is Taught,” which appeared in the April 1887 issue of the

Century Magazine

(SLC 1887).

385.1–3 At the reading in Washington . . . Thomas Nelson Page . . . all due at the White House] Clemens read at two benefits for the American Copyright League at the Congregational Church, on 17 and 19 March 1888. He had not been scheduled to read at the first one, but as an “unexpected treat” he substituted for Charles Dudley Warner (delayed by a snowstorm), reading “How I Escaped Being Killed in a Duel” (“Authors as Readers,” Washington

Post

, 18 Mar 1888, 5; SLC 1872a). Here he describes the second event, at which there were ten speakers; he read “An Encounter with an Interviewer” (SLC 1875b). Page (1853–1922), best known for his sympathetic and idealized depiction of the antebellum South, read two pieces in the “peculiar dialect of the Virginia negro.” Afterward the authors and their guests were given a lavish reception and supper in the Blue Parlor of the White House (Washington

Post:

“Local Intelligence,” 20 Mar 1888, 3; “Society,” 20 Mar 1888, 4).

385.11–13 I think that it was upon the occasion . . . prepared me for my visit . . . could look after me herself ] See the next Autobiographical Dictation (5 Mar 1906).

385.28–30 upon the occasion referred to . . . Authors’ Reception at the White House] That is, referred to at the end of the previous Autobiographical Dictation (26 Feb 1906). After his first reading at a matinee on 17 March 1888, which Olivia did not attend, Clemens went to a tea at the White House. Olivia joined him in Washington in time for his second reading on 19 March, and accompanied him to the reception afterward (16 Mar 1888 to OLC, CU-MARK, in

LLMT

, 249–51; Rosamond Gilder 1916, 195–96).

385.35–36 President Cleveland’s first term. I had never seen his wife . . . the fascinating] Cleveland served two terms, in 1885–89 and 1893–97. He married Frances Folsom (1864–1947) in the White House on 2 June 1886. She became known for her beauty, her advocacy of women’s education, her Saturday receptions for working-class women and the poor, and her liveliness and wit. The anecdote Clemens recounts here must have occurred on 17 March 1888, at the tea after his first Washington reading.

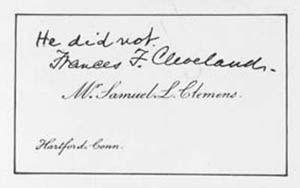

386.8–9 I asked her to sign her name below those words] The card, now in the Mark Twain Papers, is reproduced here.

386.25–27 During 1893 and ’94 we were living in Paris . . . other side of the Seine] The Clemens family stayed at the Hotel Brighton from November 1893 until June 1894, when they left the city to travel elsewhere in France, returning to Paris in the fall. There they again stayed at the Hotel Brighton until mid-November, when they relocated to the house at 169, rue de l’Université, where they remained until the end of April 1895.

386.28 Pomeroy, the artist] The English sculptor Frederick William Pomeroy (1856–1924) won the gold medal and traveling scholarship from the Royal Academy Schools in London in 1885, and subsequently studied in Paris and in Italy. He was associated with the “New Sculpture” movement, which depicted ideal figures drawn from mythology and literature. Nothing is known of his association with Clemens.

386.42–387.1 Mammoth Cave] An enormous cave in Kentucky, which by the 1890s was thought to be about one hundred seventy-five miles long; it is now known to be over twice that size (Baedeker 1893, 318; National Park Service 2008).

387.6 Four or five years ago, when we took a house . . . at Riverdale] In early July 1901 the Clemenses toured William H. Appleton’s house in Riverdale-on-the-Hudson, New York, and arranged to rent it from 1 October. They remained there through July 1903. Clemens called it “the pleasantest home & the pleasantest neighborhood in the Republic” (30 June 1903 to Perkins, NRivd2; Stein 2001, B1; 9 July 1901 to Rogers, CU-MARK, in

HHR

, 465; Wave Hill 2008).

388.13 Buck Fanshaw’s riot, it broke up the riot before it got a chance to begin] In chapter 47 of

Roughing It

, “Scotty” Briggs tells how Buck Fanshaw had an election riot “all broke up and prevented nice before anybody ever got a chance to strike a blow” (

RI 1993

, 314).

388.17–20 The Cleveland family . . . passed away] Ruth (“Baby Ruth,” 1891–1904), who died at twelve of heart failure during a bout of diphtheria, was the first of five Cleveland children, followed by sisters Esther (1893–1980) and Marion (1895–1977), and brothers Richard (1897–1974) and Francis (1903–95) (“Ruth Cleveland Dead,” New York

Times

, 8 Jan 1904, 7). Clemens wrote to her on 3 November 1892, when she was one year old, just before her father’s election to his second term (DLC):

Dear Miss Cleveland:

If you will read this letter to your father, or ask your mother to do it if you are too busy, I will do something for you someday—anything you command. For I mean to come & see you in the White House before the four years are out. I am going to have Congress enlarge it, for you will take up a good deal of room, probably. And I am writing a book for you to practice your gums on—the very thing, for I know, myself, it is a very tough book. I shall bring my arctics, but that is all right—I know what to do with them now. . . .

No Administration could be more creditable than your father’s & mother’s last one was—& yet it ain’t agoing to begin with this one, now that you are on deck.

You have my homage, & I am

Affectionately Yours

S. L. Clemens.

388.29–30 kindly send a sealed greeting under cover to me . . . South to him] Clemens complied with Gilder’s request the following day. See the Autobiographical Dictation of 6 March 1906 for the text of his letter, which Gilder sent to Cleveland in Stuart, Florida. Gilder had first met President Cleveland in the White House before Cleveland’s marriage in 1886, but their friendship began in 1887 (Richard Watson Gilder 1910, 7; Rosamond Gilder 1916, 142; Lynch 1932, 533).

388.36–39 Mason, an old and valued friend . . . Frankfort in ’78] Clemens first became acquainted with Frank H. Mason (1840–1916), his wife, Jennie V. Birchard Mason (1844?–1916), and their son, Dean B. Mason (b. 1867), in Cleveland in 1867–68. Mason worked as reporter, editorial writer, and finally managing editor of the Cleveland

Leader

from 1866 to 1880, when he was appointed U.S. consul at Basel, Switzerland. Clemens must be misremembering when he “spent a good deal of time” with Mason, since neither family sojourned in Frankfurt in 1878. The families did socialize, however, during the summer of 1892 in Bad Nauheim: Mason wrote in 1905 that his family had “kept you all in the same old warm corner of our hearts,” and recalled, “We were at the Hotel Kaiserhof, in the suite of rooms just above the ones in which Mrs. Clemens and you and the girls lived during that happy summer” (Mason to SLC, 30 July 1905, CU-MARK; “Mrs. Frank H. Mason Dead,” Washington

Post

, 26 Nov 1916, 2).

389.1 ignorant, vulgar, and incapable men . . . political heelers] Heelers, or ward heelers, were apparently so called because they followed at the heels of a political boss, sometimes acting unscrupulously in the hope of future reward.

389.4–5 Mason, in ’78, had been Consul General in Frankfort several years . . . He had come from Marseilles with a great record] Although Clemens’s account of Mason’s career is essentially correct, his dates are not. In early 1884, Mason was appointed U.S. consul at Marseilles, where within months a cholera epidemic broke out, followed by a widespread panic and flight from the city. During the ensuing year he distinguished himself by his detailed dispatches about the origins, treatment, and social effects of the disease (which was complicated by a concurrent outbreak of typhus and typhoid fever), and by his efforts to prevent its spread. By late August 1885 he reported that the panic of 1884 had subsided somewhat, but the death rate in the “reeking city” was still a “frightful record.” From 1889 through 1898 he served as consul general at Frankfurt, and from 1899 to 1905 as consul general at Berlin; his next post was in Paris (Washington

Post:

“The Cholera at Marseilles,” 8 Sept 1885, 4; “Capt. Frank H. Mason Dead,” 25 June 1916, ES11; New York

Times:

“The Cholera Panic in France,” 4 July 1884, 1; “Origin of the Epidemic,” 1 Aug 1884, 3; Department of State 1911).