Autobiography of Mark Twain (165 page)

Read Autobiography of Mark Twain Online

Authors: Mark Twain

433.21–23 After that . . . with a great deal of good care she recovered] Olivia had wished to accompany Langdon’s body to Elmira, but because of “her poor state of health,” and because she could not leave infant Susy, she stayed behind in Hartford. Clemens remained there with her, entrusting the body to Susan and Theodore Crane (Lilly Warner to George Warner, 3 and 5 June 1872, CU-MARK, in link note following 26 May 1872 to Bliss,

L5

, 98).

433.27–35 Mr. Charles Kingsley . . . They are all dead except Sir Charles Dilke and Mr. Tom Hughes] Charles Kingsley (1819–75), minister, canon of Westminster, Cambridge history professor, novelist, poet, and essayist; Henry M. Stanley (1841–1904), journalist and explorer, whom Clemens first met in St. Louis in 1867; Sir Thomas Duffus Hardy (1804–78), deputy keeper of the Public Records, but not a descendant of Sir Thomas Masterman Hardy (1769–1839), who witnessed Lord Nelson’s death at Trafalgar in October 1805; actor Sir Henry Irving (1838–1905); poet Robert Browning (1812–89); Sir Charles Wentworth Dilke (1843–1911), liberal member of Parliament and proprietor of the

Athenaeum

, a weekly journal of literary and artistic criticism; novelist and dramatist Charles Reade (1814–84); journalist and novelist William Black (1841–98); Richard Monckton Milnes (1809–85), first Baron Houghton, statesman, poet, and writer, and editor of Keats; Francis Trevelyan Buckland (1826–80), physician and prominent natural historian and pisciculturist; novelist Anthony Trollope (1815–82); Tom Hood (1835–74), poet, journalist, anthologist, and son of poet and humorist Thomas Hood (1799–1845); poet, novelist, and children’s author George MacDonald (1824–1905), his wife, Louisa (1822–1902), and their eleven children; and journalist and historical novelist William Harrison Ainsworth (1805–82). Clemens was unaware that novelist, biographer, journalist, and member of Parliament Thomas Hughes (1822–96), best known for

Tom Brown’s School Days

(1857), was also dead. When an excerpt from this dictation was published in the

North American Review

of 16 November 1906, his name had been removed from this sentence, presumably not by Clemens (NAR 6, 970). Presumably it was Olivia who furnished Susy with an account of the 1873 trip to Great Britain. For details of the Clemenses’ contacts with most of these individuals, see Clemens’s letters for 1872–73 (

L5

, passim).

433.36–38 We met . . . Lewis Carroll, author of the immortal “Alice” . . . “Uncle Remus.”] The meeting with Lewis Carroll (Charles L. Dodgson, 1832–98) came at the home of George and Louisa MacDonald, the “Retreat” in Hammersmith, but on Saturday, 26 July 1879, not in 1873. Carroll noted in his diary that day: “Met Mr. Clements (Mark Twain), with whom I was pleased and interested.” The MacDonald family gave a dramatic performance, as they had also done when the Clemenses visited on 16 July 1873 (Dodgson 1993–2007, 194–95; 11 July 73 to Smith,

L5

, 414). Clemens had been familiar with the “Uncle Remus” stories by Joel Chandler Harris since 1880 (see “My Autobiography [Random Extracts from It],” note at 217.25–27).

434.1 At a dinner at Smalley’s we met Herbert Spencer] George Washburn Smalley (1833–1916) was in charge of the New York

Tribune

’s European correspondence from 1867 to 1895 and was himself the paper’s London correspondent. From 1895 to 1905 he was U.S. correspondent of the London

Times

. Philosopher Herbert Spencer (1820–1903) and the Clemenses were among the dinner guests at Smalley’s home on 2 July 1873 (

L5:

11 June 1873 to Miller, 377–78 n. 2; 1 and 2 July 1873 to Miller, 395–96 n. 1).

434.2–3 we met Sir Arthur Helps . . . is quite forgotten now] Sir Arthur Helps (1813–75) was clerk of the privy council, a personal adviser to Queen Victoria, and a popular writer of the day, producing numerous volumes of fiction, history, and biography.

434.3–4 Lord Elcho . . . was talking earnestly about Godalming] Francis Wemyss-Charteris-Douglas (1818–1914), eighth earl of Wemyss, sixth earl of March, and Lord Elcho, was a member of Parliament and a lord of the treasury. Godalming is an ancient town in Surrey, thirty miles southwest of London.

434.7 Lady Houghton] The former Annabella Hungerford Crewe (1814–74) married Richard Monckton Milnes (Lord Houghton) in 1851.

434.12–13 I will insert here one or two of the letters . . . copied into yesterday’s record] All three of the letters Clemens inserted below were included by Jock Brown in his edition of his father’s letters (John Brown 1907, 354, 357–58, 360–61). The texts were transcribed into this dictation from the typescripts Brown had sent from Scotland.

434.14 June 22, 1876] The letter sent to Brown in 1876 was written by both of the Clemenses; in this dictation Clemens inserted only the part that Olivia had written, which followed his (for the full text see SLC and OLC to Brown, 22 June 1876,

Letters 1876–1880)

.

434.20–21 farm . . . where my sister spends her summers] Quarry Farm, near Elmira.

434.23–24 Mr. J. T. Fields . . . we talked most affectionately of you] Author and retired Boston publisher James T. Fields and his wife, Annie, had visited the Clemenses in Hartford from 27 to 29 April 1876. Fields and Clemens were parties to the 1876 campaign to raise a retirement fund for Dr. John Brown (see 17 Mar 1876 to Redpath, n. 2,

Letters 1876–1880

, and the Introduction, p. 7). Annie Adams Fields (1834–1915), a poet, biographer, and social reformer, was known for her hospitality. She entertained a wide circle of literary acquaintances at her Boston home, recording personal anecdotes of famous authors in her diaries; some of them were published in

Memories of a Hostess

(Howe 1922).

434.25 your sister] Isabella Cranston Brown (see AD, 5 Feb 1906, note at 328.30–33).

434.29 (1875)] This letter was undated, and when Hobby transcribed it into this dictation, she typed merely “(18 ).” The date now assigned to it is 25–28 October 1875 (for the text as it was sent, and the letter from Brown that it answered, see OLC and SLC to Brown, 25–28 Oct 1875,

L6

, 570–72).

434.39–41 Mr. Clemens is hard at work on a new book now . . . some few are new] The “new book” may have been one of a number of unidentified works Clemens had in mind or in progress in the fall of 1875 (see 4 Nov 1875 to Howells,

L6

, 585 n. 9). The sketchbook was

Mark Twain’s Sketches, New and Old

(1875c), which he had his publisher send to Brown on 6 December 1875 (11 Jan 1876 to Bliss,

Letters 1876–1880)

.

435.3–5 nurse that we had with us . . . quiet lady-like German girl] Ellen (Nellie) Bermingham and Rosina Hay, respectively (“Contract for the Routledge

The Gilded Age,” L5

, 641 n. 4; SLC and OLC to Brown, 4 Sept 1874,

L6

, 226 n. 8).

435.20–21 I was three thousand miles from home . . . sorrowful news among the cable dispatches] Brown died on 11 May 1882, at which time Clemens was in New Orleans gathering material for

Life on the Mississippi

.

435.35 Our Susy is still “Megalopis.” He gave her that name] In 1873 Brown gave the nickname to seventeen-month-old Susy because, Clemens later explained, her “large eyes seemed to him to warrant that sounding Greek epithet” (SLC 1876–85, 3).

435.36–37 one taken in group with ourselves] See the photograph following page 204.

436.6–8 courier in service until we got back to Liverpool . . . be done with him] Clemens seems to have confused the two couriers he employed during the family’s 1878–79 European sojourn. George Burk, a German, worked for the Clemenses in Germany, Switzerland, and Italy from early August until 1 October 1878, when he was discharged for incompetence. Joseph Verey, a Pole, worked for them in France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and probably briefly in England from 8 July until around 20 July 1879, when they reached London, giving great satisfaction during that time. The Clemenses arrived in Liverpool on 21 August and sailed for the United States two days later (

N&J2

, 48, 52 n. 16, 121 n. 17, 197–98 n. 71, 210–11, 327 n. 67).

436.25–30 Doctor was guessing at our address . . . Near Boston, U.S.A.] Brown sent two letters to Clemens in early 1874 that were returned to Scotland “Unclaimed.” According to a complaint about the post office that Clemens wrote to the editor of the Boston

Advertiser

on 16 June 1874, one was addressed “Hartford, State of New York.” In his complaint Clemens also mentioned another letter, addressed to him in “Hartford, Near Boston, New York,” which did reach him “promptly” from England (16 June 1874 to the Editor of the Boston

Advertiser, L6

, 162–63).

437.3 Menzies, the publisher] John Menzies (1808–79) was an Edinburgh publisher, bookseller, and newsagent, whose company was one of Scotland’s principal book, magazine, and newspaper distributors. The firm continues in business today and despite diversification still derives much of its revenue from newspaper and magazine distribution (Clan Menzies 2009; John Menzies plc 2009).

437.12 I think Postmaster-General Key was in office then] The postmaster general at the time John Brown’s letters were mishandled was John A. J. Creswell (1828–91), a Republican congressman and senator from Maryland (1863–65, 1865–67, respectively), who served from March 1869 until July 1874. He is considered to have been exceptionally effective, responsible for sweeping reforms that reduced costs and increased speed and efficiency of delivery of both domestic and foreign mail. David McKendree Key (1824–1900), a lawyer, Confederate soldier, and Democratic senator from Tennessee (1875–77), was postmaster general from March 1877 to June 1880.

437.19–31 Key suddenly issued some boiler-iron rules . . . the letter must go to the Dead Letter Office] Clemens alludes to the United States Postal Laws and Regulations issued by Postmaster General Key on 1 July 1879, and to supplementary orders regarding misdirected letters issued by him in September and October of that year. Postmasters and postal employees could not on their own authority change a letter’s “direction to a different person or different office or different state.” Misdirected matter received at any post office for delivery had to be returned to the sender if his name and address were on it, and if not, the item had to be sent to the dead-letter office. Letter addresses were required to include both city and state, making “New York, N.Y.” the acceptable form, with letters addressed merely to “New York City” consigned to the dead-letter office. These rules occasioned much complaint and criticism. Clemens added his voice to the protests in a letter of 22 November 1879 and two letters of 8 December 1879, all to the Hartford

Courant (Letters 1876–1880;

Bissell and Kirby 1879, 2, 117; New York

Times:

“Notes from the Capital,” 10 Oct 1879, 2; “Orders to Postmasters,” 12 Oct 1879, 2; “The Post Office . . .,” 15 Oct 1879, 4; “Imperfectly-Directed Letters,” 31 Oct 1879, 3).

438.11–12 Mark Twain, God knows where] Clemens was in London, in 1896, when he received the letter thus addressed, which had been sent (according to Paine) by Brander Matthews and Francis Wilson of The Players club (

MTB

, 2:565–66). Clemens replied:

I glanced at your envelope by accident, and got several chuckles for reward—and chuckles are worth much in this world. And there was a curious thing; that I should get a letter addressed “God-Knows-Where” showed that He did know where I was, although I was hiding from the world, and no one in America knows my address, and the stamped legend “Deficiency of address supplied by the New York P.O.,” showed that He had given it away. In the same mail comes a letter from friends in New Zealand addressed, “Mrs. Clemens (care Mark Twain), United States of America,” and again He gave us away—this time to the deficiency department of the San Francisco P.O. (24 Nov 1896 to The Players, New York

Tribune

, 31 Dec 1896, 6)

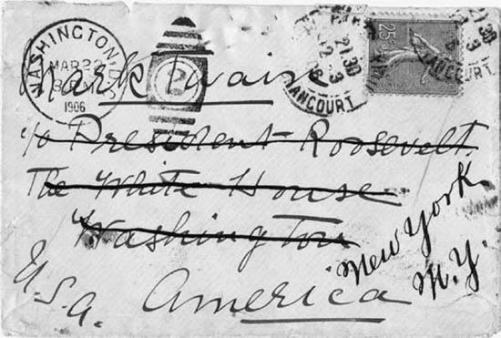

438.20–30 It comes from France . . . Washington postmark of yesterday] The envelope, but not the letter itself, survives in the Mark Twain Papers, and was once pinned to the typescript of this dictation (see the envelope with the redirected address, below).

438.31–32 In a diary which Mrs. Clemens kept . . . mentions of Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe] A diary that Olivia used sporadically between 21 October 1877 and 19 June 1902, with only twenty-five of its leaves bearing her writing, survives in the Mark Twain Papers. Just one entry mentions Harriet Beecher Stowe. Dated 7 June 1885, it describes how Stowe appeared that afternoon

carrying in her hand a bunch of wild flowers that she had just gathered. She asked if I would like some flowers, of course I said that I should. She handed them to me thanking me most heartily for taking them. Said she could not help gathering them as she walked but that when she took them home the daughters would say “Ma what are you going to do with them, everything is full” meaning with those that she had already gathered. Mrs Stowe is so gentle and lovely. (OLC 1877–1902)