Autobiography of Mark Twain (58 page)

Read Autobiography of Mark Twain Online

Authors: Mark Twain

An Early Attempt

The chapters which immediately follow constitute a fragment of one of my many attempts (after I was in my forties) to put my life on paper.

It starts out with good confidence, but suffers the fate of its brethren—is presently abandoned for some other and newer interest. This is not to be wondered at, for its plan is the old, old, old unflexible and difficult one—the plan that starts you at the cradle and drives you straight for the grave, with no side-excursions permitted on the way. Whereas the side-excursions are the life of our life-voyage, and should be, also, of its history.

My Autobiography [Random Extracts from It]

* * * * So much for the earlier days, and the New England branch of the Clemenses. The other brother settled in the South, and is remotely responsible for me. He has collected his reward generations ago, whatever it was. He went South with his particular friend Fairfax, and settled in Maryland with him, but afterward went further and made his home in Virginia. This is the Fairfax whose descendants were to enjoy a curious distinction—that of being American-born English earls. The founder of the house was Lord General Fairfax of the Parliamentary army, in Cromwell’s time. The earldom, which is of recent date, came to the American Fairfaxes through the failure of male heirs in England. Old residents of San Francisco will remember “Charley,” the American earl of the mid-’60s—tenth Lord Fairfax according to Burke’s Peerage, and holder of a modest public office of some sort or other in the new mining town of Virginia City, Nevada. He was never out of America. I knew him, but not intimately. He had a golden character, and that was all his fortune. He laid his title aside, and gave it a holiday until his circumstances should improve to a degree consonant with its dignity; but that time never came, I think. He was a manly man, and had fine generosities in his make-up. A prominent and pestilent creature named Ferguson, who was always picking quarrels with better men than himself, picked one with him, one day, and Fairfax knocked him down. Ferguson gathered himself up and went off mumbling threats. Fairfax carried no arms, and refused to carry any now, though his friends warned him that Ferguson was of a treacherous disposition and would be sure to take revenge by base means sooner or later. Nothing happened for several days; then Ferguson took the earl by surprise and snapped a revolver at his breast. Fairfax wrenched the pistol from him and was going to shoot him, but the man fell on his knees and begged, and said

“Don’t

kill me—I have a wife and children.” Fairfax was in a towering passion, but the appeal reached his heart, and he said,

“They

have done me no harm,” and he let the rascal go.

Back of the Virginian Clemenses is a dim procession of ancestors stretching back to Noah’s time. According to tradition, some of them were pirates and slavers in Elizabeth’s time. But this is no discredit to them, for so were Drake and Hawkins and the others. It was a respectable trade, then, and monarchs were partners in it. In my time I have had desires to be a pirate myself. The reader—if he will look deep down in his secret heart, will find—but never mind what he will find there: I am not writing his Autobiography, but mine. Later, according to

tradition, one of the procession was Ambassador to Spain in the time of James I, or of Charles I, and married there and sent down a strain of Spanish blood to warm us up. Also, according to tradition, this one or another—Geoffrey Clement, by name—helped to sentence Charles to death. I have not examined into these traditions myself, partly because I was indolent, and partly because I was so busy polishing up this end of the line and trying to make it showy; but the other Clemenses claim that they have made the examination and that it stood the test. Therefore I have always taken for granted that I did help Charles out of his troubles, by ancestral proxy. My instincts have persuaded me, too. Whenever we have a strong and persistent and ineradicable instinct, we may be sure that it is not original with us, but inherited—inherited from away back, and hardened and perfected by the petrifying influence of time. Now I have been always and unchangingly bitter against Charles, and I am quite certain that this feeling trickled down to me through the veins of my forebears from the heart of that judge; for it is not my disposition to be bitter against people on my own personal account. I am not bitter against Jeffreys. I ought to be, but I am not. It indicates that my ancestors of James II’s time were indifferent to him; I do not know why; I never could make it out; but that is what it indicates. And I have always felt friendly toward Satan. Of course that is ancestral; it must be in the blood, for I could not have originated it.

... And so, by the testimony of instinct, backed by the assertions of Clemenses who said they had examined the records, I have always been obliged to believe that Geoffrey Clement the martyr-maker was an ancestor of mine, and to regard him with favor, and in fact pride. This has not had a good effect upon me, for it has made me vain, and that is a fault. It has made me set myself above people who were less fortunate in their ancestry than I, and has moved me to take them down a peg, upon occasion, and say things to them which hurt them before company.

A case of the kind happened in Berlin several years ago. William Walter Phelps was our Minister at the Emperor’s Court, then, and one evening he had me to dinner to meet Count S., a cabinet minister. This nobleman was of long and illustrious descent. Of course I wanted to let out the fact that I had some ancestors, too; but I did not want to pull them out of their graves by the ears, and I never could seem to get a chance to work them in in a way that would look sufficiently casual. I suppose Phelps was in the same difficulty. In fact he looked distraught, now and then—just as a person looks who wants to uncover an ancestor purely by accident, and cannot think of a way that will seem accidental enough. But at last, after dinner, he made a try. He took us about his drawing-room, showing us the pictures, and finally stopped before a rude and ancient engraving. It was a picture of the court that tried Charles I. There was a pyramid of judges in Puritan slouch hats, and below them three bare-headed secretaries seated at a table. Mr. Phelps put his finger upon one of the three, and said with exulting indifference—

“An ancestor of mine.”

I put my finger on a judge, and retorted with scathing languidness—

“Ancestor of mine. But it is a small matter. I have others.”

It was not noble in me to do it. I have always regretted it since. But it landed him. I wonder how he felt? However, it made no difference in our friendship; which shows that he was fine

and high, notwithstanding the humbleness of his origin. And it was also creditable in me, too, that I could overlook it. I made no change in my bearing toward him, but always treated him as an equal.

Jane Lampton Clemens, Keokuk, Iowa, Photograph by George Hassall.

Pamela Clemens Moffett, early 1860s. Courtesy of Mrs. Kate Gilmore and the Mark Twain Boyhood Home and Museum, Hannibal.

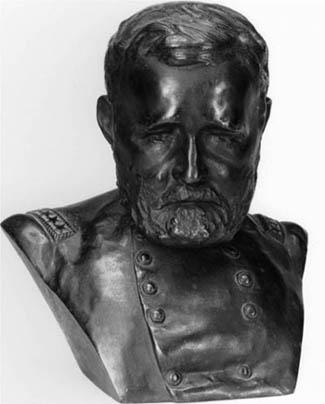

Orion Clemens, early 1860s. Nevada Historical Society.

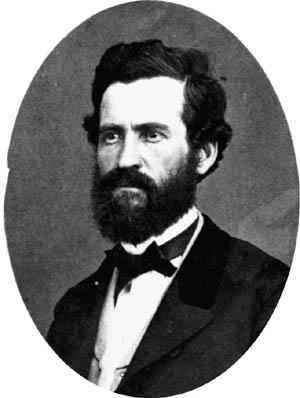

Henry Clemens, ca. 1858. Mark Twain Boyhood Home and Museum, Hannibal.

Samuel L. Clemens and Olivia L. Langdon. The porcelaintypes in purple velvet cases they exchanged during their engagement in 1869. His photograph was taken by Edwin P. Kellogg, Hartford.

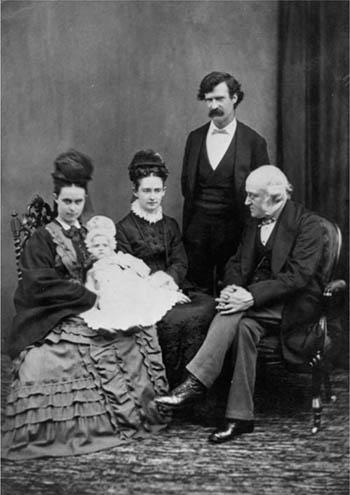

Clara Spaulding with Susy Clemens in her lap, Olivia and Samuel Clemens, and John Brown, Edinburgh, August 1873. Photograph by John Moffat. Mark Twain House and Museum, Hartford.