Autobiography of Mark Twain (61 page)

Read Autobiography of Mark Twain Online

Authors: Mark Twain

Clemens at his seventieth birthday dinner at Delmonico’s, 5 December 1905, with Kate Douglas Riggs, Joseph H. Twichell, Bliss Carman, Ruth McEnery Stuart, Mary E. Wilkins Freeman, Henry Mills Alden, and Henry H. Rogers. Photograph by Joseph Byron, New York.

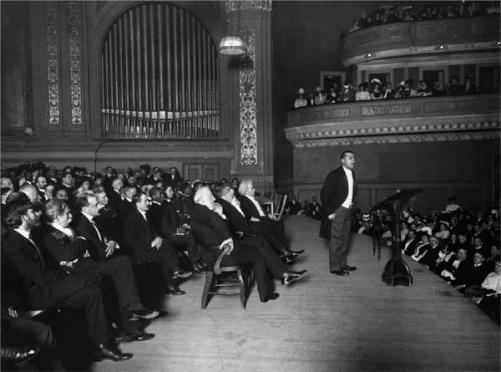

Booker T. Washington speaking on behalf of the Tuskegee Institute at its “silver jubilee” celebration, with Clemens sitting behind him on stage at Carnegie Hall, 22 January 1906. Photograph by Underwood and Underwood.

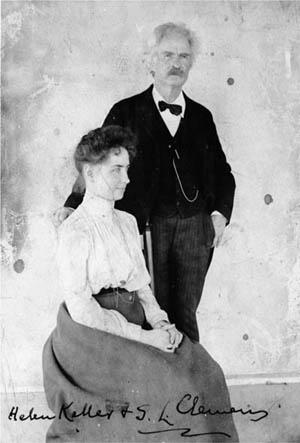

Helen Keller and Clemens, 1895. The inscription is in Clemens’s hand.

Clemens and Henry H. Rogers outside the Princess Hotel, Bermuda, 1908. Photograph by Isabel Lyon.

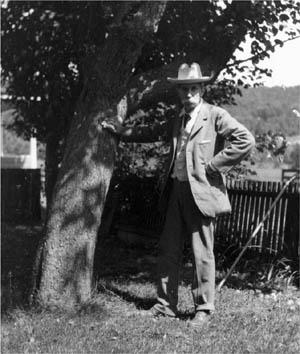

Joseph H. Twichell and Clemens, February 1905. Photograph by Jean Clemens.

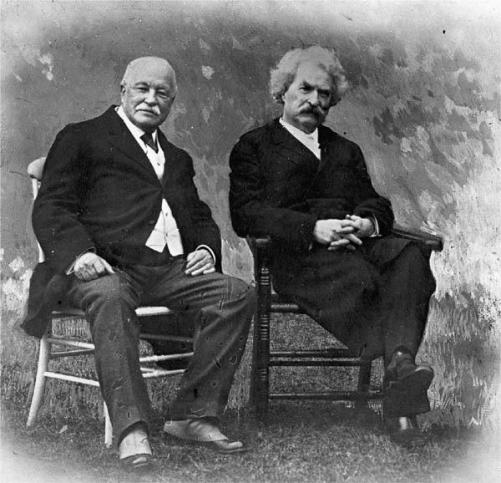

William Dean Howells and Clemens, Lakewood, New Jersey, 28 December 1907.

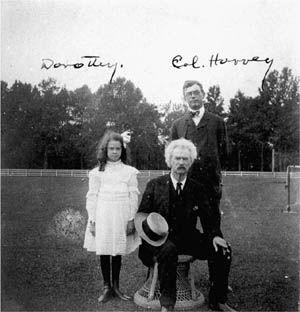

Dorothy and George Harvey with Clemens, ca. 1903. The identifications are in Clemens’s hand.

Richard Watson Gilder, October 1904. Photograph by Jean Clemens.

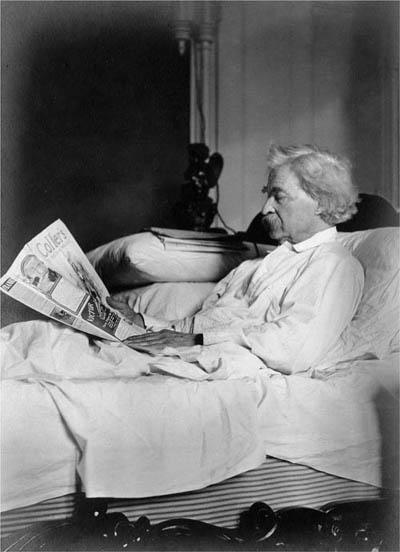

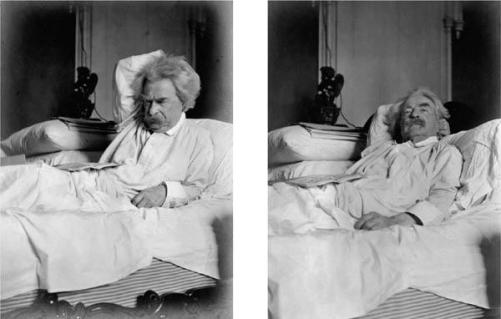

Three views of Clemens in his bed at 21 Fifth Avenue, New York, from a series of photographs taken by Albert Bigelow Paine in late February or early March 1906. In the top photograph, Clemens is reading the 24 February 1906 issue of

Collier’s Weekly

with the morning newspapers piled on the pillow next to him.

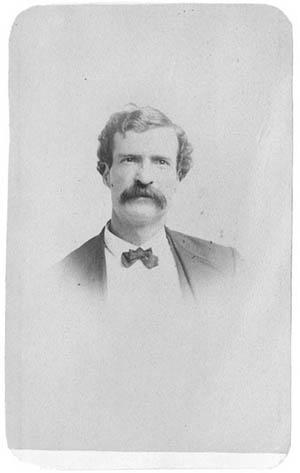

Samuel Clemens, Boston, Massachusetts, 1869. Photograph by James Wallace Black. Courtesy of Kevin Mac Donnell.

But it was a hard night for me in one way. Mr. Phelps thought I was the guest of honor, and so did Count S.; but I didn’t, for there was nothing in my invitation to indicate it. It was just a friendly off-hand note, on a card. By the time dinner was announced Phelps was himself in a state of doubt. Something had to be done; and it was not a handy time for explanations. He tried to get me to go out with him, but I held back; then he tried S., and he also declined. There was another guest, but there was no trouble about him. We finally went out in a pile. There was a decorous plunge for seats, and I got the one at Mr. Phelps’s left, the Count captured the one facing Phelps, and the other guest had to take the place of honor, since he could not help himself. We returned to the drawing-room in the original disorder. I had new shoes on, and they were tight. At eleven I was privately crying; I couldn’t help it; the pain was so cruel. Conversation had been dead for an hour. S. had been due at the bedside of a dying official ever since half past nine. At last we all rose by one blessed impulse and went down to the street door without explanations—in a pile, and no precedence; and so, parted.

The evening had its defects; still, I got my ancestor in, and was satisfied.

Among the Virginian Clemenses were Jere. (already mentioned), and Sherrard. Jere. Clemens had a wide reputation as a good pistol-shot, and once it enabled him to get on the friendly side of some drummers when they would not have paid any attention to mere smooth words and arguments. He was out stumping the State at the time. The drummers were grouped in front of the stand, and had been hired by the opposition to drum while he made his speech. When he was ready to begin, he got out his revolver and laid it before him, and said in his soft, silky way—

“I do not wish to hurt anybody, and shall try not to; but I have got just a bullet apiece for those six drums, and if you should want to play on them, don’t stand behind them.”

Sherrard Clemens was a Republican Congressman from West Virginia in the war days, and then went out to St. Louis, where the James Clemens branch lived, and still lives, and there he became a warm rebel. This was after the war. At the time that he was a Republican I was a rebel; but by the time he had become a rebel I was become (temporarily) a Republican. The Clemenses have always done the best they could to keep the political balances level, no matter how much it might inconvenience them. I did not know what had become of Sherrard Clemens; but once I introduced Senator Hawley to a Republican mass meeting in New England, and then I got a bitter letter from Sherrard from St. Louis. He said that the Republicans of the North—no, the “mudsills of the North”—had swept away the old aristocracy of the South with fire and sword, and it ill became me, an aristocrat by blood, to train with that kind of swine. Did I forget that I was a Lambton?