AWOL on the Appalachian Trail (8 page)

Read AWOL on the Appalachian Trail Online

Authors: David Miller

After Roan Mountain, there is a series of grassy balds, providing views back to Roan. Here I meet two thru-hikers from England, Spoon and Martin. Both are strong hikers. Spoon is in his twenties. Martin is a character. He's in his early forties, small, wiry, intense, with knobby calf muscles and a smile like a terrier baring teeth. His reddish-blond hair matches his skin tone, giving him a monochromatically ruddy appearance. He is smoking, and surely he's a drinker, too. And yet, later, Spoon would tell me that Martin runs marathons. "Last time he finished, he ran right past the check-in and on into the first pub he could find."

At a fork in the trail, we go left along a blue-blazed trail a hundred yards to Stan Murray Shelter. A day hiker is here, planning to stay the night. I plan to go on to the next shelter. I head south back down the blue-blazed trail on which I came in. The day hiker says, "North is that way," pointing to the blue-blazed trail that continues north beyond the shelter.

8220;Yes, I know," I respond, but I continue to go back the way I came in.

Some shelters are situated with side trails coming in from two points on the trail, one south of the shelter, and the other north of the shelter. Martin explains to the day hiker that if I were to take the other side trail back out, I would not be walking the section of the AT between the two side trails. This is part of the purist thru-hiker code to which, thus far, I am still adhering. I get back to the AT and head north. I notice that I am walking parallel with the side trail, virtually retracing my steps. The shelter comes back into view, and I walk past it a mere ten yards away. The side trail was hardly necessary. I feel silly as I again wave "bye" to Martin, Spoon, and the day hiker after my two-hundred-yard diversion. They are still discussing the finer points of purist thru-hiking.

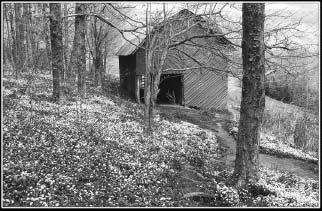

Overmountain Shelter is a defunct barn with room for dozens of hikers. Sixteen show up tonight. The setting is wonderful, overlooking a valley of cleared land. The side of the barn facing the valley is open, and downstairs there are plywood platforms for sleeping. Spoon and I lay out our bags here, but a wispy rain blows inside. I move to the enclosed upper deck--hayloft sans hay--where most of the other hikers are, spread out at odd angles laying claim to the most even patches of the rickety plank platform.

Overmountain Shelter.

Muktuk pauses on his way to the privy, full roll of toilet paper in hand. Most hikers unwind a fistful of toilet paper and stuff it in a plastic bag, hoping it lasts until their next resupply. "This is one thing you don't want to run out of," Muktuk says, mocking our preoccupation over pack weight. Now that he has an audience, he discourses on the pros and cons of nitpicking over a few ounces. "I met a hiker named 'Go Heavy' who carried his stuff in four suitcases. He'd carry two of them a hundred yards or so, leave them, and go back for the other two. He was intense. You know the kind; he had huge veins popping out on his neck and forearms." Muktuk's story is replete with hand gestures, waving a cigarette in one hand and toilet paper in the other.

I enjoy the crowd and the enthusiasm that we all have at this point in our hike. We've been on the trail long enough to make friends and to have experiences to talk about. We feel like we've been tested, and we all think we will finish. There is much ahead of us to be eager about.

Crossroads is here, on floor space next to me. We have our legs in our sleeping bags and are journaling and planning by headlamp. He has a map, and we talk of how the terrain is supposed to get easier now. I'm hoping to get to Damascus in three long days. My supplies are dwindling. I've just eaten two of my dinners, and I've finished the loaf of bread I bought two days ago. I can't get enough food. I'm shivering in my bag, and it's not that cold. I lack body fat to keep me warm.

There is barely a drizzle, as if the fog is too heavy to stay airborne, when I leave Overmountain Shelter. My feet are soaked less than an hour into the day. The first three miles are open and grassy with outcroppings of huge boulders. It probably would be scenic in good weather, but blanketed in fog it looks like a scene from

Macbeth.

The rain would last with varying intensity all day.

I spook four deer, a buck and does. This makes me consider putting in a request for reincarnation as a deer. But I'd probably get shot so they could mount my antlers on a bunny skull at some steakhouse.

The next stretch of the trail in northeastern Tennessee was made possible by eminent domain land grabs that didn't sit well with the locals. Hikers tread lightly here. I pass with ears peeled for dueling banjos. The trail crosses a paved road, where there is an ominous sign warning of vandalism and advising against leaving cars parked at the trailhead. There are more road crossings, paved and unpaved. Few buildings are within sight of any of the crossings. Trash is dumped at one roadside where the trail crosses. I see a makeshift, handwritten "Shelter" sign, pointing down a side trail, and I wonder if it is an attempt to lure hikers off the trail. Barking hounds, distant gunfire, and rusty remnants of barbed wire fences add to my uneasiness, but my passage is uneventful.

Before starting my hike, about half of the people I spoke with showed a great deal of concern for security on the trail, much more concern than I had myself. "Are you going alone?" "Are you taking a gun?" All questions showing disbelief that I would venture out unarmed among deranged, inbred mountain folk.

I went to a gun shop to buy some pepper spray. Better safe than sorry; something small just to give me peace of mind. The guy behind the counter was exactly what you might expect: big, gruff, bearded, tattoos, and one earring.

"Do ya want somethin' fer four-legged critters or the two-legged kind?"

"Both, I guess. What would you take?"

"I'd take me a gun. And a big knife, like that one," he answered, pointing to a Rambo model. "Ya see, if I wuz a low-life up there, I'd just hang out near that trail and get me some easy pickins."

So I got the pepper spray, but not the peace of mind.

The trail parallels the Laurel Fork River for a few hundred yards. Near the bank, a hiker is standing in the rain like a sentinel, wearing a poncho. His pack is off at his feet, leaning on his legs.

"Hi."

"Just taking a break," he says. "Wish this rain would stop." Rain drips off the hood of his poncho and runs down his face. Droplets hang in his beard. Both of us are too weary for conversation.

I "hit the wall" after twenty miles and have a new assortment of blisters from walking with wet feet. The last six miles are a struggle. There are a number of stream crossings. The water is narrow enough to step over, but the banks of the stream have eroded, forming a deep "V" of land that I have to negotiate. Lunging across the gap hurts my feet. I stop and sit on a wet stump to put a bandage on the worst of the blisters. I have to stop thirty minutes later when the bandage peels off and forms a lump in my sock. Mud extends up the inside of my legs, where I nick each calf with the opposite foot. The large blister on the back of my heel, the one I popped in Erwin, is a mass of loose, soggy, white skin.

I arrive at Laurel Fork Shelter with just enough light to cook. Four other hikers are here already. Two are day hikers, and two are thrhikers. None of the other thru-hikers from Overmountain Shelter did this wet, twenty-six-mile walk. I have a spot in the shelter next to one of the thru-hikers, an older gentleman with dense white hair and beard, with looks that place him between Santa Claus and Richard Harris, with the demeanor of the former. His trail name is Tipperary, named after the county in Ireland that is his home.

At this point on the trail, most thru-hikers have trimmed the fat from their packs and from their bodies. There is a notable absence of hikers who don't have it together. Few look like they don't belong, and Tipperary is one of the few. He's carrying a heavy sleeping bag and a seven-pound tent. Although he has already lost forty pounds, he is still overweight, and he has his sore knee in a tight wrap. I introduce him to the wonder drug ibuprofen. In my mind, I unfairly judge that he won't be finishing the trail. Hearing of my long day, Tip treats me as if I am a trail master. We are both wrong.

Less than half the shelters so far have had a picnic bench, and this one does not. At most shelters, there is a fire pit out front. Hikers drag logs around the fire for seating. Here, I am seated on a skimpy branch only eight inches in diameter. It hardly qualifies as a log. I see pinholes in it, and the tiny red bugs that made them. It is an awkward place to make dinner. My stove burns isobutane, a gas that is compressed into a canister about the size and shape of an upside-down soup cup. The canister serves as the base for my stove. The stove itself only weighs four ounces and screws onto a threaded nipple on top of the fuel canister. It's just a burner with wings to support a small cook pot.

I have pasta for dinner. I cook pasta in one pot and dehydrated sauce in the other, then dump the pasta into the pot with the sauce. The pasta pot is still considered clean. For breakfast, I make the meal that I have most often, two packets of instant oatmeal and hot chocolate. I don't carry a cup, so I mix hot chocolate in the smaller of the two pots. When I finish the oatmeal, I pour hot chocolate into the pot I ate from. This cleans out the oatmeal; I drink the dregs in my hot chocolate.

It is raining again today. I make a short day of it, hiking only six miles to Kincora Hostel. I wanted to stop here anyway, since it is a renowned trail stop. Owner Bob Peoples has built the hostel in a building adjacent to his own home, a few hundred yards from where the trail crosses Dennis Cove Road. Bob is retired and works as a trail maintainer. Thru-hikers stop in to shower, wash clothes, and stay the night, all for the charitable price of four dollars.

Bob drives a truckload of hikers into town, and we quiz him about his work as a trail maintainer. He says the dumping of trash that we've seen near road crossings has gone on for years. He has picked through the trash, looking for anything that might identify the perpetrator, but the trash has always been scrubbed of identifying material. The animus towards hikers in this region comes in part from Irish landowners who had their land taken away to make the AT corridor more than twenty years ago. A long time to hold a grudge? Not for families who have owned the land for generations. Bob himself is Irish; Kincora is taken from the name of a castle in Ireland.

Next year, Bob will be rerouting part of the trail south of here. He assures us that the new trail will maintain a low grade and won't go over peaks unless there is a view. I'll believe it when I see it.

A group of us are early enough to make it to the lunch buffet at Chopsticks Chinese Restaurant. Later, when another wave of hikers arrives at Kincora, Tipperary and I tag along for a second trip to town. Spoon is here for this trip, and he and I split a pizza. Then he eats half a dozen doughnuts.

There is a talkative bunch at the hostel, happy to have reached the four-hundred-mile mark and eager to get to Damascus, Virginia, just fifty-one miles away. We load up the couch and every other sit-able surface for a group discussion. Tipperary wings me with his elbow whenever he is tickled by the conversation, which is often. I do surgery on my shoes. The tendon just above my left heel is raw because the padding on that part of my shoe has deteriorated. I cut a lumpy seam from the inside back of my shoe. The Dude has the same problem. His solution is to get a ride to Damascus to buy new shoes. He's a handsome young man, with utter confidence in his ability to charm his way to Damascus and back.