AWOL on the Appalachian Trail (25 page)

Read AWOL on the Appalachian Trail Online

Authors: David Miller

Buckeye arrives shortly after I do, and we share a motel room. He hiked the southern half of the trail in 2002 and is doing the northern half this year. Buckeye is also in town to escape the bad weather. "If we were paid to do this, we would have quit by now," he says. Obviously his joke rests on the fundamental enigma of the trail: why do we voluntarily, happily (mostly), submit ourselves to tribulation? Aside from the spectacular moments, aside from the gratification of working to accomplish a goal, there is ownership. This endeavor is much more endurable because we "own" it. We are here by choice, and we are going about it in the way of our own choosing.

My inevitable return to work has crept into my mind, and I mingle my thoughts. In

The Snow Leopard

, Peter Matthiessen notices that sherpas are cheerful in their work and often do more work than they are paid for, even though they earn a pittance. He observes the sherpa belief that "it is the task, not the employer, that is served" and that "the doing matters more than the attainment or reward."

34

This seems to be an attitude worth striving for when I return to work,

to perform my job as if I was doing it under my own guidance--as I would want it done myself--not to limit myself to the role of employee, and not to refrain from giving more of mye job than is warranted by my pay. It is I who would benefit. Time is most enriching when spent industriously.

The motel clerk drives me back to the trail in the morning. The walk up from the road is gradual, with a manageable amount of mud. I arrive at the Goddard Shelter a little after 2:00 p.m. This shelter is at an elevation of 3,540 feet. Early into Vermont, the trail is already at a higher elevation than at any point in the past four states. There is a clearing in front of the shelter and I look out to tall and spindly pines, but the sky is too overcast to see the horizon. Vermont is the twelfth state on the trail, and I have less than six hundred miles to go. For more than half of my hike I viewed my overall progress as the number of miles I had under my boots. I remember noticing when I had completed one hundred, five hundred, and one thousand miles. Now the important number is the number of miles remaining. I am in countdown mode. I've averaged over one hundred miles per week, so for the first time I have a firm grip on my finish date; six weeks from now will be the middle of September.

There are already a handful of hikers in the shelter, including Odwalla, Buckeye, and Jerry Springer. Raindrops spot the dusty porch of the shelter. More hikers arrive. I am torn between claiming a spot in the shelter or moving out in the drizzle. I've only traveled ten miles. Rainfall intensifies, blowing so hard that we string ponchos and tarps across the shelter front to keep the sleeping platform dry. I'm staying put.

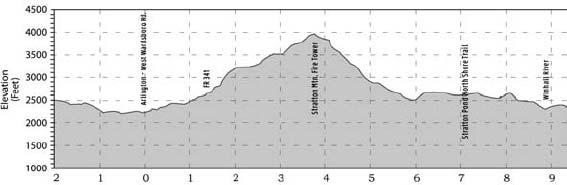

There are five more hours of daylight. For the eight of us holed up in the shelter, it is a restless time. When conversations lull, I write letters and catch up on my journal. Jerry Springer has a filter for brewing coffee on a camp stove. He shares, and it is excellent. I spend some time looking over my guidebook and making plans for the next few days. Odwalla has trail maps, and I take a look at the profile of the trail ahead. The town of Manchester Center is exactly thirty miles away. I've already hiked over twenty miles on thirty-seven days of this journey, but I've yet to do thirty miles, and the idea is enticing. The days over twenty miles are always trying, but a thirty-mile day is a challenge. It would be a new experience to add to my adventure. I try to recruit Odwalla, but he is not interested. From the look of the map, I can see why. Stratton Mountain is an imposing obstacle in the middle of the stretch. It is four thousand feet high, and I will have to walk twelve miles before even starting the climb. It would've been wiser to do my long day in the midsection of the trail, but it is too late for that. The days are already getting shorter, and further north the terrain will only get harder. I will try for thirty tomorrow.

Profile map showing eleven miles of the AT encompassing Stratton Mountain.

I am off early in the morning in a damp fog. Even if I was able to backpack at three miles per hour without stopping, I would be in for a ten-hour day. I can't sustain that speed, and I'll have to take breaks. I am in for at least twelve hours of intense hiking, and there is hardly that much daylight.

This part of Vermont has a deep forest look to it. Ferns cover the ground, streams cut across the trail, and spongy green moss covers the rocks and creeps up the tree trunks. Wet pines are wonderfully aromatic. And there is mud--mud stamped with hundreds of deep, water-filled shoe prints. Stratton Mountain won't be the only thing slowing me down. The trail is concave from wear down the enter, and so it is an incubator for mud. I try to walk on the outer edges, but trees and dense undergrowth prohibit it. Where there is leeway it gets trampled as well, so the muddy trail bed bulges out like a recently fed snake. Hikers before me have thrown branches and stones onto the path, trying to bridge the muck. Shelter registers are full of entries by hikers complaining about the conditions, referring to the state as "Vermud."

There are heady moments when I strut down the trail, strong and untiring. I'd like to convince myself that I am in perfect equilibrium and can go on indefinitely. It is just walking--it can't be that hard. But I've been at it long enough to know it doesn't work that way. Changes creep in with the stress of miles. A hot spot flares up on my foot, the pack belt cuts into my hipbone, rain pesters me, my knee tightens, and hunger suddenly makes me feel weak. Heavy legs tell me to put my weight on my butt for a while.

I'm up and over Stratton Mountain by 3:30 p.m. I've made good time under the circumstances. I have twelve miles to go and about four hours of daylight. The trail is relatively level the rest of the way. At 7:30 it's getting dark and I'm racing for the road. I worry about trying to hitch in the dark. I scramble out to the road at dusk. To my relief, it's lighter than in the woods, and the first car to pass gives me a ride to town.

I stay at a boarding house in the center of town. It is more like a hostel, and the only guests are hikers. I will stay in town tomorrow.

I spend my zero day walking all over town. I do laundry, eat breakfast and lunch at restaurants, and visit the library. An immense Orvis fishing store, their flagship store, is on the same road as the library. There is a pond on the grounds where fly-casting practice is taking place. Students are flicking the flies down with a splat, their teacher alongside them unrolling lazy loops of line across the surface.

Dharma Bum and Suds are on a curb looking over a map. As I approach I see that the map is not a trail map, it is of the state. Frustrated by the wet weather, they are looking for someplace other than the trail to spend the next few days.

Manchester Center is a pretty town, a little larger than other trail towns, and it's swollen in the center with brightly advertised factory outlet stores. The stores are dispersed, many having their own buildings. There are more high-end stores than would seem supportable in this rural location: Armani, Ralph Lauren, Coldwater Creek, and Timberland are among the offerings. The stores have no draw at all for me. Months of scrutinizing everything that I carry have conditioned me to view possessions as burdens. I do spend time at two of the outfitters. I am unhappy with my pack and my shoes are coming apart, but I do not find suitable replacements. The outfitter tells me of a family who will let thru-hikers stay overnight.

I hitch out to the home, which is on the edge of town near the trail crossing. It is a nice piece of property with a house and a barn. The couple who own the home have hiked the entire trail and still do maintenance work on the trail. Their basement is set up for hikers, with a few beds, an assortment of trail books, and a refrigerator. I am the only hiker staying tonight. I use the evening to work on my pack.

The "internal frame" of my backpack is two aluminum bars on the opposite side of the pad that rests against my back. The top of the bars tuck into a plastic flap near the top opening of the pack. The bars help to transfer the weight of the load down to onight. ip belt. After a thousand miles of bouncing, the bars have worked loose from the plastic flap. The weight of the pack falls on my shoulders, like an old-fashioned knapsack, instead of being distributed by the frame. Also, the plastic flap wedges awkwardly between the bars, tilting the load to one side. I stab holes through the plastic, wrap string around the supports, and cauterize the whole mess with my stove. While I am at it, I cut out the internal compartment intended for water bottle storage, a feature that I quickly found to be impractical. I clip off all unused straps and trim excess length from straps I use. I had refrained from these customizations, thinking that I may sell the pack later. But no one, including me, is going to want the pack after this trip is over. With my pack thus MacGyvered, I'm ready for the AT once again.

Acquaintances and strangers who have read my journal and sent messages of encouragement tell me how thrilling it sounds to thru-hike the AT. I don't think I've put an unduly positive slant on my journal, but they are more inclined to relate to the pretty pictures and good times than the everyday effort of carrying a pack. "I am totally engrossed and so envious!" "WOW! What a great adventure." Today, I feel it perhaps as they do, looking at my environment with fresh eyes and seeing the wonder of it anew. I'm a lifelong resident of Florida. I recall coming to the Appalachians as a kid on family vacations, awed by the expanse of mountains, the trees, the fresh air, and the cascading streams. These are my thoughts as I make my climb up Bromley Mountain.

The trail leads into a grassy clearing about ten yards wide. The clearing looks like it continues all the way to the top; this must be a ski slope. At the top, I can see the lift cables, a warming shack, and a sign pointing to my ski slope, the "Run Around." Looking north, I can see that I have a bit of up-and-down trail ahead of me. The trail descends from Bromley on a moderate to steep decline through a mix of moss, mud, and boulders. I pull out a Pop-Tart and eat as I descend, knowing that I should be attentive to footing on this slippery trail. The mountains are waterlogged from days of rain. I even pause before one fateful step across the slippery rock slope. Sure enough, I go down, still clutching at my Pop-Tart. I'm able to hold on to it through my long backslide, but I crush it in my clenched left hand. I watch longingly as one large crumb of my fractured meal bounds into the bushes. The whole thing happens in slow motion.

I've put a deep scratch in the face of my watch, but I still have some of my precious Pop-Tart. I couldn't care less about my backside; I don't even bother to brush off. Instead I stand and start funneling the crushed tart into my mouth, shuffling forward like a food-obsessed idiot. A few feet later I slide again, resuming my luge downhill. This time I lean right to keep my food hand airborne. At times like this it's good not to have a hiking partner.

Rain falls lightly and intermittently throughout the day, but overall it is a pleasant and scenic day. Jerry Springer is resting in a stately hemlock forest. The forest floor is matted with needles, and there are also a number of stones. Hikers have stacked the stones to build temples befitting the landscape. Jerry is just standing idle with his pack off, taking in the solemnity of the scene. I see a couple that I've not seen on the trail before. They pick up their pace when I come up behind them, and they seem perturbed when they finally pull aside to let me walk past, too perturbed to respond to my "Thanks."

I have lunch at the well-engineered Peru Peak Shelter. The roof extends far beyond the sleepingplatform. No rain will be blowing in here, as it did at Goddard Shelter. The couple I passed earlier arrive, and they pause for a minute and run their eyes over the shelter. They still have said nothing to me. "What do you think of this one? One to ten?" the man asks of his partner.

"Five," she says definitively, the man nods in agreement, and they turn to walk on. They couldn't be talking about me; a five out of ten rating would be too generous. They are insulting the shelter! I've seen enough shelters to know this is a good one. Their aloofness I can handle, but a poor assessment of this fine shelter has me cursing muddy trail slippages upon them.

I stop for the night at Big Branch Shelter. The Big Branch River runs in front, cascading over boulders and making a soothing racket. I am the only guest, and I fall asleep reading a dog-eared paperback copy of

Shane

that was left in the shelter. I am awakened at 11:00 p.m. when two hikers arrive by headlamp and settle in.

When I am ready to leave in the morning, the hikers are just getting up. They are Nooge and Tucker, college-aged thru-hikers who started the trail over a month before I did. I had passed them a few weeks ago without meeting them. They are in great shape, but they had been dawdling. Now, they have to average thirty miles a day to finish before college starts, sometimes hiking into the night.