AWOL on the Appalachian Trail (20 page)

Read AWOL on the Appalachian Trail Online

Authors: David Miller

I am intrigued when I overhear a small group of hikers talking about Elwood. I move closer with my plate of food and ask if they will start the story over, from the beginning. Elwood had stayed at Bears Den Hostel (on the day that I last saw him) and left without paying for the stay and food. The people who ran the hostel called ahead to the Blackburn Center to alert them that Elwood might be on the way. Elwood must have been wary when he checked into the Blackburn Center because he checked in using the new trail name "Peg Leg." Also, he said he was thru-hiking southbound. But there were other thru-hikers who knew who he was and reported him to Bill, the caretaker. The police were called, and when they pulled up, Elwood donned his pack and made a break for the woods, only to be run down by Bill and a couple of hikers and held for the police. In addition to nonpayment at Bears Den, he had been pilfering gear from other hikers, and he was rumored to have an outstanding warrant. The police had Elwood empty his pack. His stash included a handful of pocket knives and oddball pieces, like a cookpot lid without the matching pot. Some of the stolen items belonged to hikers present at the Blackburn Center when Elwood was caught.

Everyone clusters together for a group photo, using the seats and tops of picnic benches to stand at different levels in order to get everyone's face in the picture. The photographer, a Red Blazer, leans on the open tailgate of a pickup truck. Everyone has given her cameras, so nearly thirty cameras are lined up on the tailgate. Hikers get impatient and goofy while posing for so many shots and start making different faces and gestures for each shot. They razz the photo taker when she has difficulty working one of the cameras. Many shouts of "Tipperary!" ring out, and I see him traipsing down the road, the last to arrive.

The morning is dewy and quiet; the town is asleep. There is little noise coming from the field of tents near the pavilion, just a couple of hikers trying to collapse their tents without waking anyone. I sneak down the road, under a bridge, and back up into the woods.

If the town was bigger, I would've considered a zero day. I feel somewhat ragged from walking fairly long days since leaving Pen-Mar Park. My mail drop is at the Port Clinton Post Office, which is closed for the weekend. I will call and have it forwarded when I have the opportunity, but that doesn't help my current shortage. There is nowhere to resupply. I dismiss my concerns about supplies; it feels good to be winging it, leaving my plans to fate.

I see few of the hikers who were at Port Clinton during my day. Some of the nicest views anywhere on the Pennsylvania leg of the AT are from areas called the Cliffs and the Pinnacle. The Pinnacle is an elevated shelf of rock overlooking a patchwork of farmland. The squares below stand out crisply under clear skies, all in different shades of green. There are nearly a dozen people out on the rocks, all of them just out for the day.

Coming down from the Pinnacle, the trail descends steadily for miles along the gravel road that has delivered the tourists. Near Eckville Shelter, about fifteen miles from Port Clinton, I cross Hawk Mountain Road, where a car is parked. A canopy has been erected, and there sits thru-hiker Scubaman with his parents. His parents have come to visit him and are set up to do trail magic. They've brought a handful of folding chairs, a cooler, and they are grilling hamburgers. This is the most opportune bit of trail magic I would receive on the trail: late in the day, when least expected. Before the trip I guessed my food cravings would be for pizza, ice cream, and Mexican food. All of these I have wanted at some point, but my most persistent craving is for hamburgers and cold drinks. This is surprising, since these were things I infrequently consumed in my "real" life.

The food helps power me up the last climb, through the rocks, to the peak of Dan's Pulpit. For the second time today, I stop to write. Also, I scribble down some of the items I'll need when I get to a store. Most pressingly, I need another fuel canister. For all the towns I've passed in Pennsylvania, I've not been to an outfitter. I'm lucky to have stumbled into a free dinner tonight because I only have enough fuel to cook one more meal. There is a mailbox with "register" written on the side, oddly placed on this inconsequential peak. Registers away from shelters are rare. I open the box to sign the register and find that someone has left behind more trail magic--a full fuel canister!

There were over thirty hikers in Port Clinton yesterday, and I am the only one to pick the Allentown Hiking Club Shelter as a stopping place tonight. It is odd how hikers get distributed along the trail. The last time I had a shelter to myself was back in Tennessee. It is already dusk when I lay my pack down. Fireflies play in the trees, and mosquitoes visit the shelter.

North from Allentown Shelter the going is easy, at some places following dirt roads and at other places following a path so wide and gentle that it could be used by a car. I am bothered by piercing pain under the middle toe of my right foot. I have only a small blister, but it causes insidious, torturous pain, like it has burrowed into a nerve. Twice I stop to tape and pad around the blister to little avail. I am worried about reaching an impasse so early and on such easy terrain. How will I handle the rest of the day, and all the days beyond? I pause for a rest, take painkillers, and filter water from a deep, fast-moving stream that is tea-colored from tannin. When I get going again, I am successful at getting focused on other things. But the trail gets very rocky.

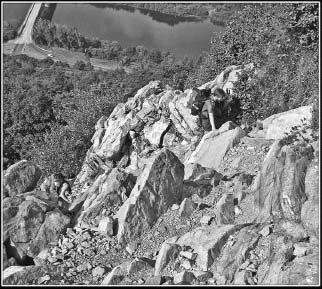

I stand knee deep in boulders on Bake Oven Knob, looking back on the rubble I just ascended. Rambler is churning his way uphill, so I wait and let him pass. The boulders are large enough for me to make multiple steps on top of each boulder, gradually increasing in size until I am walking on bedrock, the source of all boulders. The surge of bedrock narrows, like the underside of a ship's hull protruding up through the surface of the hill trailed by a wake of rocks. The trail is right along the keel, elevated fifteen feet above ground. Coming to a stop at the stern, I see no blazes and wonder how I'm supposed to get down. Did I get off the trail? I can reach out and touch the upper limbs of trees rooted in the ground below, but there are no limbs firm enough to climb down upon. I notice a bulge, just large enough to get a toe-hold, and back off the rock. Near the spot where I descended, there is a white blaze, indicating that the rock scramble is the intended path of the AT.

The trail only momentarily reenters the woods before once more leading up a similar rock pile. The ridge of the second rock pile is much less uniform and more elevated, leaving a jagged cliff edge on both sides of the narrow path. The path is riddled with fissures and scree. What's more, these rocks are sloped and have a dusty layer of dried mold on them, so that footing is uncertain.

Skittles and Trace are at Bake Oven Knob Shelter.

27

I met Skittles at Port Clinton, but this is my first opportunity to speak with T

race. Skittles sits on the shelter platform with a family-sized bag of Skittles; Trace and I sit on logs outside. Trace is a young, big guy, not too many years past his days of playing college football. He has his jersey number team-mate-tattooed into his shoulder.

Rambler returns from a side trail with his water bottle, shaking his head in frustration. "That's a long way to get water...I had to go all the way to the third sign to get it."

"I should have told you," Skittles says, "that I found water off the trail between the first and second springs."

I had taken the blue-blaze trail to get water. The first spring I came to was dry, and a note had been left which read: "If spring is dry, the next spring is 0.4 mi. downhill. If the second spring is dry, continue approx. 0.1 mi. to next spring." I did not pursue it, inadvisably gambling that I would save myself a mile-long round trip and find a more convenient water source later. I also have a policy of keeping small the number of different locations from which I take water, believing that it will lessen my chances of drinking contaminated water. For the remainder of the day the trail never crosses a stream, and I end up having to make a long trek down a side trail anyway.

"How 'bout those boulders back there," Trace comments to the three of us. We all know what boulders he is talking about, the second stack that I had encountered.

Rambler replies, "That really looked dangerous."

"I was wondering if I was the only one that felt that way [scared]," Skittles says, sounding relieved that he wasn't the only one who was timid on the cliffs.

"I wouldn't want to do it in the rain. You fall off that, and you're going to have a lot worse than a broken leg," Rambler notes. "Don't screw around there. You could get killed."

"I thought the same thing. Slip here and you die," Trace reiterates. We laugh at the bluntness of his statement.

My three companions are fit young men, and they are challenged, at times intimidated, by the obstacles. I think how impressive it is that so many retirees, grandparents, and kids take on the AT. They have stiffer joints, shorter strides, and less strength, but still find a way to negotiate dangerous terrain like the boulders of Bake Oven Knob. There are no handicap ramps or guardrails. We are all walking the same trail.

A few miles beyond the shelter, I run out of water. The trail runs along the top of a low ridge, in places open to the hot sun. Fortunately, the sunlight is also conducive to blueberry growth. I stop frequently to harvest clumps of plump berries. Somewhere below, the Pennsylvania Turnpike tunnels under the mountains. I hear a faint rumble from the highway, but I cannot see the road. I am parched and tired and lament my decision to forgo water. The intense sun tires my eyes, and I stagger on in a dreamlike state. The sound of traffic plays on, stuck in my mind like a song, long past the point where it was last audible. Lehigh Gap is nearby, and the remainder of the trail is mild and smoothly downhill. I don't suffer much for the mistake of running out of water, but it was a mistake I should not have made. I had eliminated any margin of error. If I had gotten lost or injured, my situation could've quickly become desperate.

In Pennsylvania, the trail towns are conveniently spaced about every twenty miles, more suited to my pace than the shelters. My plan for the next three nights is to stay in Slatington, Wind Gap, and Delaware Water Gap.

In Slatington, I stay at a hotel called Fine Lodging, where the adjective "Fine" must refer to what is paid to the housing department. The hotel is not at all a hotel in the Holiday Inn sense of the word. The building is a three-story wood-frame structure with about a dozen rooms. There are narrow sub-marinelike hallways with matted carpet. A few additions have been made to the original structure, and where they meet the floors don't match up. Little ramps in the hallways make up the difference. The walls seem to lean, making me feel unsteady. I walk with one hand brushing along the wall for balance. I wonder if I can wobble the building if I shake hard enough. Only a few rooms are available for nightly rental.

The owner has stored excess furniture in the room where I will stay. There are three dressers, and an extra bed is propped on edge. There is no air conditioning and no room phone. There is a pay phone in a niche off the hallway, and all rooms on this floor share a common restroom and shower. I lock the door when I leave to take a shower, but I notice that slight pressure on the door will push it open anyway. My room looks down over Main Street, where boisterous youth who are loitering at the street corner yell out at boisterous youth in cars with bass-pounding radios. All building the street look the same--silty, old, and forgotten. It is too hot to close the windows. I pull closed the threadbare, yellowed curtains and go to sleep to the din of slow-moving traffic.

The trail grows steeper and rockier as it ascends from Lehigh Gap. I have to pick my way around and climb over boulders, using my hands nearly as much as my feet. It is a beautiful morning, and I stop often to take in the steep view back down to the Lehigh River. On one of my stops I notice hikers coming up the trail behind me. Our slow progress up the mountain compresses the space between us, so we end up climbing together in a chain. Eight thru-hikers packed together on the trail is a rare occurrence. We stay together for the last three hundred yards to the summit of Blue Mountain, giving each other a hand up the more difficult sections, all of us appreciating the adventure, challenge, and camaraderie instead of being flustered by the obstacle.

After the climb, the trail continues for a couple of miles over rocky, deforested hills. Skeletons of trees killed by zinc smelting protrude from the rocks.

Stretch, Skittles, Trace, One-Third, and Odwalla are among the hikers on the climb. I meet thru-hiker One-Third for the first time. She is a recent college graduate who started the hike with her parents, but she is the last of the three who is still thru-hiking. Her parents had to quit due to illness, but they still hike when they can and visit One-Third periodically. Odwalla is roughly the same age as myself and is recently divorced. His trail name came from Odwalla food bars, which are a staple of his trail diet.